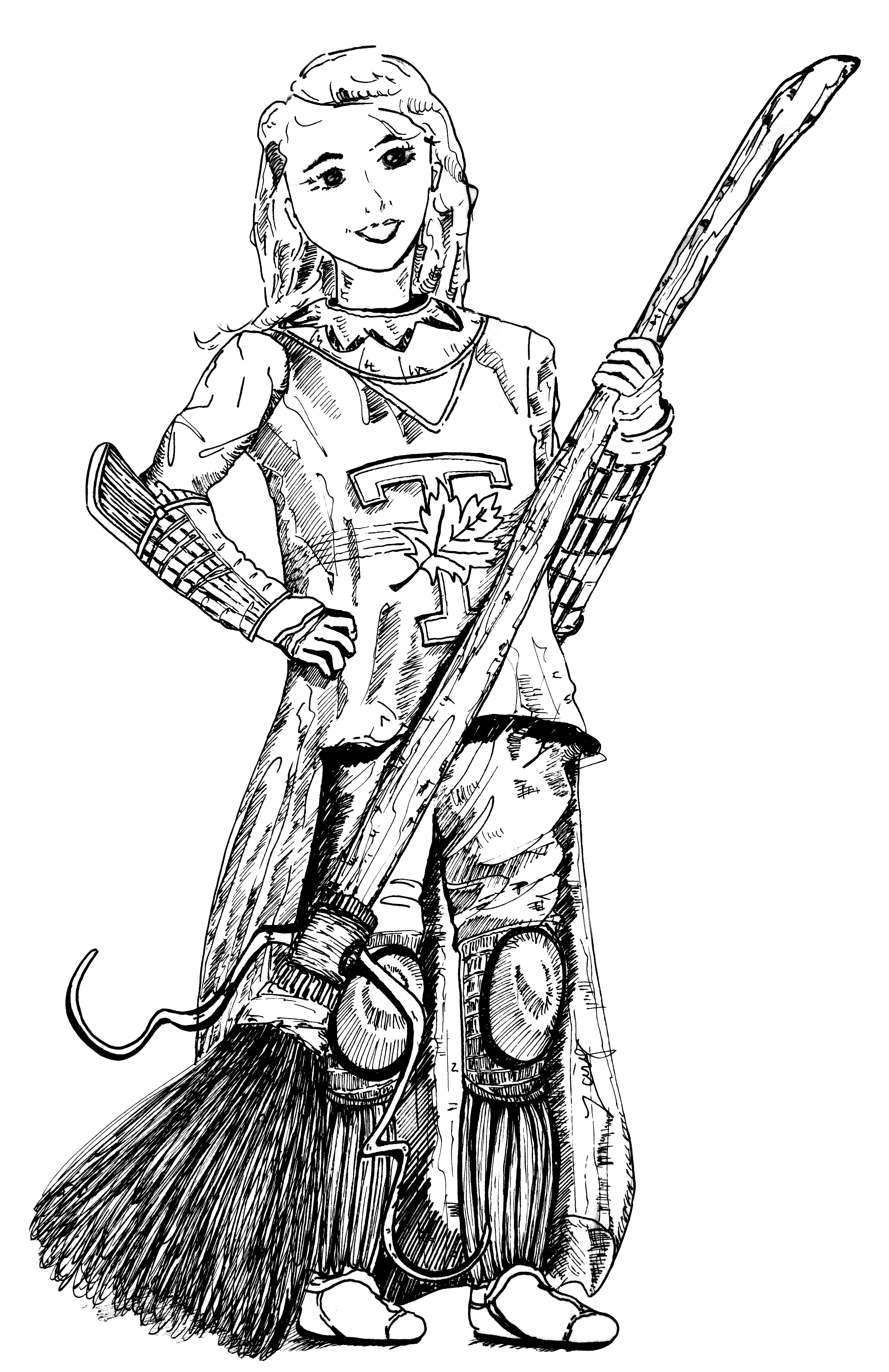

A University of Toronto sports team spent the last weekend of October competing against teams from across the country, vying to be crowned Canada’s best. But unlike their fieldhockey or soccer counterparts, the U of T Nifflers aren’t an official Varsity Blues team, and their chosen activity, Quidditch, isn’t an official intercollegiate sport.

U of T finished last at the inaugural Canadian Quidditch Cup, hosted by Carleton University in Ottawa. “[It] sucks, because I feel like if we could get points on our spirit and enthusiasm, we would definitely come in first place,” said Rachel McCann, fourth-year chemical engineering student and this year’s team captain.

U of T finished last at the inaugural Canadian Quidditch Cup, hosted by Carleton University in Ottawa. “[It] sucks, because I feel like if we could get points on our spirit and enthusiasm, we would definitely come in first place,” said Rachel McCann, fourth-year chemical engineering student and this year’s team captain.

The Nifflers started with a 0–90 loss to the University of Ottawa. Ottawa won in aggressive fashion, striking Toronto’s chasers with heavy offensive pressure.

Toronto scored their first points of the tournament against McGill, the nation’s top-ranked Quidditch team. Despite losing 10–270 in the first game and then 30–180 in the second, McCann recalls chanting with her teammates, “We scored a goal! We scored a goal!” against the stalwart McGill team.

Inspired by the success of McGill, U of T is beginning to implement similar game strategies. “McGill keeps their beaters back near the hoops, and they always have bludgers (dodgeballs); so if anyone comes close to their hoops, they get hit,” explained McCann. “They’re like a defensive wall and it works very well.”

The Nifflers won their last game against Ryerson in overtime with a final score of 140–90.

Despite propping up the standings, U of T walked away with the “Most Attractive Team Award,” first-year student Susan Gordon gleefully explained.

Toronto came agonizingly close to ranking seventh in the Canadian Cup. The win against Ryerson was no surprise to McCann who said, “[Ryerson is] quite small so we usually beat them.”

“It’s kind of sad,” whispered McCann, giggling a little.

Quidditch is a fast-growing sport at U of T. “The team quadrupled in size from last year,” noted McCann, with over 200 signatures on Clubs Day, 80 try-outs, and 50 members for what is technically only a campus club.

Despite the lack of official intercollegiate status, the Nifflers’ main competitive opponents are teams from other universities. Beyond the Canada Quidditch Cup, U of T normally competes at the Quidditch World Cup, a competition organized by the International Quidditch Association. U of T is ranked 77th by the IQA, a magical non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the sport of Quidditch.

Given the team’s growth, the world of intercollegiate sports could one day welcome Quidditch to the fold. Only a gifted divination professor could tell you for sure.

Quidditch is as physically demanding as many other “regular” sports. The best players are fierce and graceful. “[When] you think [of] Quidditch, you think of Harry Potter nerds, and you think it’s going to be a dainty little sport,” McCann pointed out. “Every single person would be shocked [at] how aggressive it is.”

In “Muggle” Quidditch, chasers try to shoot the quaffle (a volleyball) through their opponent’s hoops, which are defended by keepers. Meanwhile beaters try to slow down the offense with bludgers, and seekers go after the (human) snitch. Players make up for their lack of flying ability by dutifully carrying their broomsticks between their legs.

Quidditch is also a spectators’ treat. Theatrics abound, with the golden snitch’s capture ending the match in a dramatic flourish, and scoring the team a final 30 points. The “snitch” has a sock and ball hanging from his or her waist, and is typically played by a cross-country runner. During the Ryerson game, the snitch took off in a car forcing the seekers to jog behind for part of the way.

Its roots in fantasy aside, Quidditch has the same athletic integrity as other interuniversity sports. “I always say you don’t have to know a lot about Harry Potter to play Quidditch,” said McCann, who admits that she’s no Harry Potter connoisseur.

“If [people] actually played and got hit, they’d know [Quidditch] isn’t a joke,” Gordon noted, listing the catalogue of injuries the team sustained in Ottawa. One player acquired a bruised eye from a broomstick incident, while another had a fat lip after being hit in the face with a bludger.

There is no snickering at the idea of Quidditch as an intercollegiate sport, even from those in the Blues management. “I don’t want to validate whether or not a sport is a sport based on whether it’s Varsity,” said Beth Ali, Director of High-Performance and Intercollegiate Sport, her eyes sparkling with warm familiarity for Harry Potter. “I want to validate a sport as a sport based on whether it’s physically active, if the participants enjoy it, if there’s really good leadership, [and] if people are coming together in life-long activity.”

Ali recalls watching the Quidditch team practice on the backfield of Trinity College. “They were in the rain and cold,” Ali said. “Tell me that’s not passion.”

Ali is cautious about the prospects of Quidditch at an intercollegiate level. “It’s a careful process to make sure that there is truly the capacity [for a sport to become intercollegiate],” she said. “There has to be a process, because resources are involved, and U of T is a very big place, with lots of varied interests.”

For their part, the Nifflers are content to remain a free-spirited mélange of students for now; the players have no dreams of Varsity Blues status. “It doesn’t matter where you come from, what college you’re in, what year you’re in, your race, your religion, [or] how old you are,” McCann said. “We’re all from U of T and we’re here to have fun.”

The Dumbledore’s Army at Victoria College concurs. “The brilliant thing about Quidditch is that it truly is a sport for all,” said Samantha Summers, President of the DA.

“It combines traditional elements of athletics with literature and the virtues championed in the Harry Potter series. The result is a sport which encourages competition and personal growth, both on and off the pitch, while focusing strongly on building positive relationships between players rather than animosity.”

With the good feelings, and despite the casual atmosphere, Quidditch may eventually have enough of a following to meet the criteria that Ali outlines for intercollegiate teams: “officiating, coaching, player development, facilities, [and] financial resources to operate the program.” Don’t be surprised then, if you open up The Varsity to see the U of T Nifflers with an OUA or CIS banner, and a few bruises to match.

How does a sport become intercollegiate?

Sports teams must start as clubs, before attaining Varsity status and then competing in OUA and CIS programs. According to Beth Ali, there is a “process by which you apply to become an OUA program, which starts with 10 athletic directors signing an intent to enter for a specific sport. And if there are 10 universities and directors that say they want a sport to become OUA [level], then they go into a review process.” CIS-status requires another set of processes.

There are three levels of sports in the OUA sports mode: “market-driven, high-performance, [and] varsity clubs (competitive clubs).” There are also regulations that come into play when a sports team gains Varsity status, for example “course load requirements [and] drug education requirements.”