In first year, I convinced my parents to help put me up in residence at New College. Calling what I experienced total freedom would be incorrect. I made compromises with my roommate and adhered (mostly) to college rules, but those were marginal concessions. At first, living in res was a real pleasure.

But as time went on, I discovered that the students I lived with were a tad studious for my taste and were largely serial introverts. It wasn’t the social environment I’d been pining for in the months leading up to September. Sure, I didn’t have to answer to my parents, but the arrangement wasn’t perfect.

Over the course of my university years, I’ve pretty much seen it all. From frats to shared flats to moving back in with the fam, I’ve had my share of university living arrangements and each one has its ups and downs. Many students won’t have a choice at all, either with parents too far from campus or with the only affordable option being to stay with the ‘rents. So, where do you live?

Co-op

Having moved to Toronto from Windsor, fourth-year sexual diversity studies student Natasha Novac discovered student co-ops early on as a cheap and gratifying living option. Natasha lived in co-ops for her first three years as a student and considers herself an advocate of the co-op system… with a few reservations.

“One of the reasons why I loved and lived in co-op for so long was because the rent was reasonable, generally under $600 for a prime location downtown in chic, well-maintained houses,” says Natasha.

[pullquote]What initially struck me was that these guys were providing beer — this was a big deal.[/pullquote]

“For students and housing newbies, co-op does a lot of legwork for you: it buys groceries, provides basics like toilet paper and laundry detergent, and has a wonderfully talented and devoted maintenance staff — those dudes can fix anything, seriously.”

The co-op system depends heavily on shared responsibility, through housemates divvying up errands such as cleaning and buying groceries. But while the co-op approach may seem ideal, it’s not without its flaws.

“Sometimes people move in who can’t or don’t want to build community, and the whole co-op system falters when some people refuse to pull their weight,” says Natasha. She now rents in the private market but continues her involvement with Campus Co-op as a director for the organization.

Going Greek

Early on in my university career, I was exposed to the Greek system. I received frequent invites early in my first year to a fraternity that I would soon join. What initially struck me was that these guys were providing beer — and with alcohol being the valuable commodity it is to young university students, this was a big deal.

I spent some time witnessing what life was like in that place. The house had huge parties, regular video gaming sessions, and a strangely appealing aura of unapologetic testosterone. So I moved in. Parental support persisted.

As it turned out, the spot wasn’t quite the student dwelling utopia that I’d dreamt of. The frat house was run with some of the responsibility-sharing tenets of the co-op system, but the standard as to what constituted an acceptable mess was low.

Even so, I probably could have lived with the constant stench of beer in the air and the unrelenting kitchen chaos. It was the lifestyle that grew old, along with a realization that the institution was severely lacking in inclusivity.

Shared rental

After the frat house, my next undertaking was a rental in the private market. I moved into a house near Harbord and Bathurst with two close friends, along with three strangers. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t receiving financial support for rent since working in a computer store allowed me to sustain myself for a time.

At the beginning, it was wonderful. A shared enthusiasm for electronic music, film, and photography allowed our collective creative calling to flow through the walls. We’d have guests come in the evenings and stay all night listening to music with no complaints from any of us. A few times, we even stayed out all night and watched the sunrise from our roof.

But a rising sun wasn’t the only thing over the horizon. So was a gradual accumulation of stress that was about to make life very difficult. When a flatmate didn’t pay the gas bill we lost our hot water. Personal conflicts arose. The computer store that I was so dependent on went out of business, and while looking for formal employment, I had to manage ongoing costs with a combination of odd jobs and credit card cash advances. After walking away from a less-than-ideal living environment, with a less-than-ideal level of debt, I felt I had no other choice, so I moved back with my parents.

Back home

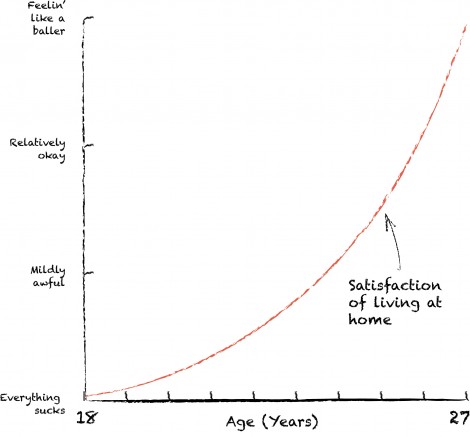

My return home wasn’t much fun at first. The parental grief seemed endless. When I wasn’t hearing about some housekeeping obligation that I’d failed to fulfill, I was being lectured on the dangers of smoking. When I’d come home late or play music too loudly at the wrong time of day, soon I’d be having a conversation with an exhausted and grouchy parent who was “already having a tough time falling asleep.”

Professor Roderic Beaujot at the University of Western Ontario has observed the phenomenon of young adults waiting longer to stake their own space away from their parents — a direct result of steep rents in even the most affordable accomodations.

“Economic forces especially play a role to keep young adults at home,” says Beaujot.

“The interest of young people today is to maximize their credentials with all the firepower that’s possible before leaving.”

In his paper, “Delayed Life Transitions,” Beaujot examines the changing landscape of parent-child relationships with respect to living arrangements. Citing Canadian census statistics, he notes that 27.5 per cent of Canadians aged 20–29 lived with their parents in 1981, a level which increased to 41 per cent in 2001. Beaujot claims that this trend is connected to greater economic exchanges from parents to their children (rather than from society to the children), but he also acknowledges a cultural shift.

“It’s now more acceptable for young adults to live at home; there’s a lessening cultural gap between parents and their children. A greater comfort with parents allowing their children to be intimate with partners at home is also more common,” explains Beaujot.

Social media is offering families new ways of staying in touch with their kids when they move out; some of us know this truth too well. On the other hand, second-year U of T computer science student Steve Tsourounis found that tweeting with his mom while living on campus allowed them to connect.

“After moving downtown, I feel like me and my mom got a lot closer because we would call each other more. She ended up getting Twitter, so she would know everything that was happening in my life,” he explained.

After spending his first year in residence at St. Michael’s College, Steve moved back with his parents in Vaughan. He notes how his social life has deflated since last year.

“Living downtown, I had a pretty active social life and was going out a lot. Now that I’m home, it’s only once every few weeks that I go out,” says Steve. But he’s not living a socially desolate existence by any means.

“Most of my friends that I grew up with live in Vaughan, so it’s not really a problem in that sense.”

Of course, social interaction isn’t limited to making it out to huge clubs, band showcases, or pub crawls. Egin Kongoli, a third year poltical science student, spent his second year of school living with his parents in North York. He found the experience was sometimes lacking in those smaller, subtler interactions.

[pullquote]The house had huge parties, regular video gaming sessions, and a strangely appealing aura of unapologetic testosterone. So I moved in. Parental support persisted.[/pullquote]

“My social life didn’t suffer in the ‘partying’ sense. Being an only child and [being] so far from any friends, I will say that I definitely did get lonely. It’s the small social stuff you start to miss out on, like just watching some TV or hanging out — doing nothing.”

With the help of hospitable friends, Egin was able to mitigate some of those feelings by crashing downtown often.

“It was nice to couch surf with friends, because I got a bit of that experience there; waking up and waiting for someone else in the house to wake and hang out with.”

For his third year, Egin returned to residence at Victoria College.

*

As for my own return home, eventually, many of the initial problems started to get resolved. As it happened, I did quit smoking. My hours of operation slowly started shifting towards something more agreeable to my parents’ (and to that of society, I’ll add). We even teamed up to renovate our house’s third floor. Socially, living with my parents has become a pleasure, with us co-ordinating social events to mix the young with the slightly less young.

The shift in parental relations came not from some grand catalyst, but rather a gradual process of communicating to the end of developing mutual respect for each other as adults. And of course, things aren’t perfect; learning how to coexist with my parents is a continuous exercise.

More of us are staying with our parents for longer periods of time. The ways that we communicate and relate with our families are changing. But there are timeless aspects of the university student’s living experience. There will be those with couches to offer and those to fill the couches. There will be some who live in res, and some who live with their parents. There will be — oh, excuse me, I have to push off; I think I hear my mother calling me for dinner.