I could criticize Robert Pattinson for lacking charisma on-screen, but thus far, it seems to be working for him. As with his melancholy vampire in the Twilight saga, most of Pattinson’s lovelorn characters seem to demand that he act with a short emotional range.

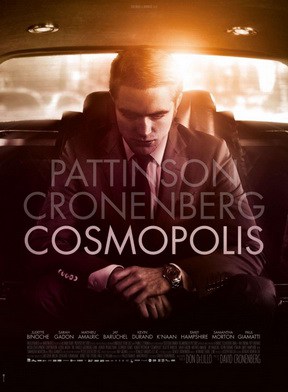

In director David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis, Pattinson’s frigidity is yet again excused by the character; Eric Packer, a young, multi-billionaire asset manager who spends a day crossing New York’s 47th street in a limousine, all for the sake of a haircut.

In spite of his vast wealth, all Packer really wants is a haircut from his childhood barber on the other side of town. Cronenberg must be toying with his audience; the film follows Packer on a surreal odyssey, or more accurately, oddity, in determined pursuit of something as pedestrian as a haircut. On his tour, Packer faces frozen traffic thanks to the visiting U.S. President, and witnesses a protest “against the future” that resembles the Occupy Wall Street movement. The protestors in Cosmopolis, however, have adopted a rat as their new currency.

Various characters appear, talk, and then disappear from Packer’s limo, including his art dealer/mistress (Juliette Binoche), his financial advisor/social commentator (Samantha Morton), and his chief of finance (Emily Hampshire). Having bet against the rising yuan, Packer is losing his fortune, and his empire is crumbling, but he doesn’t care. And when a disgruntled ex-employee, played passionately by Paul Giamatti, shoots at Packer, the sharp tycoon is remarkably slow to react.

Eschewing the shrewd, type-A businessman that is typical of today’s Wall Street melodramas, Cronenberg opts for a reserved and even philosophical lead character. But the lengthy and verbose conversations that consign Packer to a chair for most of the film threaten to alienate the audience as they sit in their own chairs in the theatre. Cosmopolis is a cerebral film, but not an accessible one.

The film relies on rapid-fire banter that would make Aaron Sorkin blush, courtesy of the source material, Don DeLillo’s novel of the same name. During a recent press conference, Cronenberg described DeLillo’s language as “realistic, but also very stylized.” The director’s oxymoron reflects a competition between content and form that characterizes much of the film: potentially valuable social commentary buried six feet under weighty DeLillesque chatter.

I say “chatter” because one couldn’t really call the characters’ conversations “dialogue”. The actors spew out their lines as though splattering paint onto a blank canvas. The result is a mess that will be indecipherable to many, but still something to wonder at, not unlike the art of Rothko and Pollock, which bookends the film.

Cosmopolis will likely divide audiences, as it has critics, because viewers have different thresholds for narrative plausibility. What transpires on screen will force the audience to suspend belief, until their disbelief is hanging by a thread. But to evaluate the film for realism would be to fundamentally misunderstand the intellectual and philosophical discourse that permeates the characters’ exchanges.

I personally admire Cronenberg’s daring. Cosmopolis is a cinematic curiosity; to some, it may seem misshapen (much like Eric Packer’s prostate). My recommendation is to get in the car and go with the flow of the traffic. I predict future viewers will pull this one over, ask, “what happened?” and find brilliance.