Apologists for radical change are rarely greeted with open arms. Too often, environmentally-inclined advocates for drastic departures from the status quo are dismissed as hippies. Stanford professor Mark Jacobson, who gave a series of sociotechnical lectures to both the public and U of T graduates and faculty groups last month, is far easier to embrace, though he maintains an admittedly monumental vision.

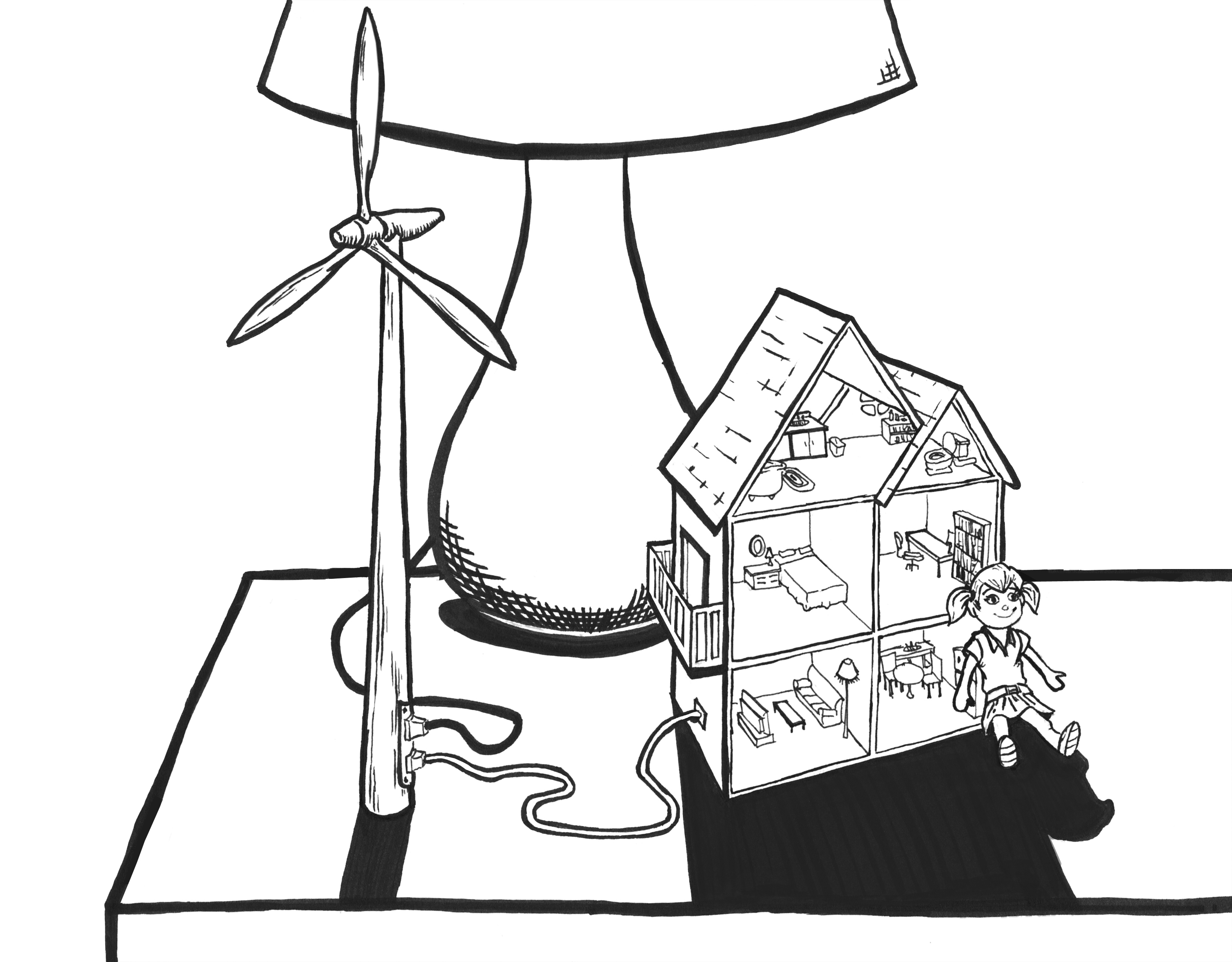

Jacobson is a straight-laced, intellectually-versatile, well-groomed idealist with a game-changing plan: a complete re-tooling of our modern energy system to be 100 per cent powered by WWS (wind, water, solar) renewable energy. Out are the old mainstays — nuclear, coal, natural gas — along with some ostensibly-helpful new technologies that will actually wreak havoc if deployed on a massive scale — biomass, biofuels, and biodiesel.

This is hardly a new dream. Indeed, whenever formal or informal conversations move into conjectures on the future of the 21st century, renewable energy invariably makes an appearance. And with good reason — fossil fuels have wrought extensive environmental damage, negatively impacted human health, and wiped trillions of dollars worth of “natural capital” — lakes, air, and rainforests — off the map. Even the most ardent of the fossil fuel titans have realized that current global energy supply mix is untenable, and tentative steps in the renewable energy direction are being made.

But how might this new world, powered by renewables and devoid of fossil fuels, look? Enter Jacobson. In a number of academic papers in notable journals like Energy Policy, he outlines a set of sources for weaning our interconnected economy from conventional fuels. This is not some pie-in-the-sky philosophizing; Jacobson is part of a vanguard team of Silicon Valley billionaires, Hollywood actors, and blue-chip academics that want to address each of the concerns of the fossil fuel lobby and its many supporters.

In his talks, Jacobson addressed many of the oil and gas industry’s key talking points head on. Can our grids handle intermittent power supply? Yes, according to Jacobson, and even moderate investments will reap big returns in the long-term. Is this plan going to raise consumer electricity rates? Yes, he acknowledges, but no more so than they would be raised through the inevitable new fossil fuel builds that will be required to replace our aging energy infrastructure. Will there be other tangential benefits? Of course, he argues, estimating that the health care savings in New York State alone could be in the range of over $30 billion per year.

Jacobson acknowledges that his analysis contains some big assumptions. Lack of political interference from citizen groups wary of the effects of wind farm development? Check. Huge increases in the availability of currently economically unfeasible elements like lithium from a variety of different locales? Yes. Little to no geopolitical instability in volatile countries like South Africa and China? Yes. It seems like an awful lot will have to be well-coordinated and seamlessly rolled out, but Jacobson is very optimistic.

It is also worth considering that the sociopolitical barriers to change are enormous. Powerful vested interests make rapid transitions unlikely, and well-funded lobby groups are likely to stay well funded. Our finance system is oriented towards short-termism and quarterly profit gains, so the chances that Jacobson’s proposed changes are implemented are small.

Can it be done? Only time will tell, but Jacobson’s contagious enthusiasm suggests there is hope.