When journalist Daniel Pearl’s murder was filmed 11 years ago in February 2002, his death crystallized a perspective on press safety that had been a long time in the making. Kidnapped in Pakistan while covering a story on militant Islamists for the Wall Street Journal, Pearl was forced to decry his American citizenship and Jewish heritage for the camera before being beheaded, and American media covered the story with vigour. The New York Times lamented that

[pullquote]“The terrible irony of Mr. Pearl’s murder is that he and other independent journalists have been trying to present a detailed and informed portrait of the mindset, motives and grievances of the Islamic fundamentalists in the wake of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 and the war in Afghanistan. That work will continue despite the killing, but the kidnappers have only undermined their cause by their acts.” [/pullquote]

By focusing on Pearl’s obviously horrendous murder as a risk taken by dedicated journalists abroad, The Times emphasized the popular American narrative of an impartial journalist under fire, risking his own life to bring the truth of the story to readers at home. While this explanation might have rung true in the case of Daniel Pearl, it fails to accurately capture the nature of press fatalities and the impact that journalist deaths have on media independence, worldwide.

In the aftermath of Pearl’s slaying, the Committee to Protect Journalists (cpj) issued a manual on protecting journalists in the field, recommending that news networks provide self-defence classes and body armour for their staff abroad. At the same time, the cpj acknowledged most press fatalities are actually local journalists, killed in the same place they live and work. The networks and blogs these journalists work for cannot afford expensive protection, and furthermore, while some local press may be killed in the line of fire, covering protests or wars, most are deliberately targeted because of their profession, either because of their perceived biases or simply because of the nature of journalistic work.

While conflict and violence are some of the events most frequently covered by journalists abroad, the cpj reports that of the 366 journalists killed between 1993 and 2002, only 60, or just over 16 per cent, were killed by crossfire. The other 306 journalists were hunted down and murdered, and their deaths frequently go unreported or under-reported in the world media — unless the victim was a western journalist abroad. In most cases, journalists were killed to prevent them from reporting on human rights issues or corruption, or as retribution for having done so. That we so rarely hear of their deaths questions The Times’ commentary on Pearl’s murder: “independent” journalists the world over are killed because of their reporting, and their work is inherently valuable, but in general, American and Western media do not value it. We tend to romanticize the deaths of our own journalists while ignoring the deaths of others.

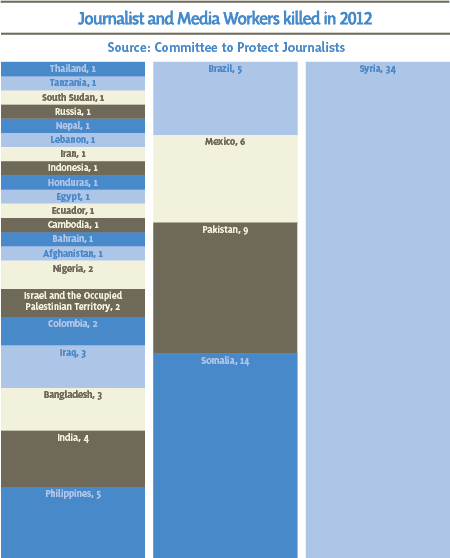

The current situation in Syria provides a perfect backdrop for examining the various ironies of press endangerment and the ensuing impact on journalistic integrity. In 2012, Syria was the location of a plurality of media deaths: 28 of the 70 journalists that the cpj lists as having been killed as a direct, confirmable result of their work died in Syria. These deaths included photographer Remi Ochlick and reporter Marie Colvin, who were killed together in a shelling of their makeshift shelter in Homs, a year ago February. Their deaths, though incidental fatalities of their location rather than targeted killings, received intensive coverage. Colvin, a veteran American journalist who had entered Syria despite attempts on the part of its government to prevent foreign press from covering the uprising, and Ochlick, a young French photojournalist, were extensively mourned, their coverage and bravery praised.

Concurrently, however, both Syrian rebel forces and loyalists of Syrian government were openly targeting journalists perceived to be supporting the opposing side. While some of these journalists worked for local news stations or papers, many of them are simply described as freelancers, either videographers or bloggers, who were covering what is being referred to as “the first YouTube war,” where men with guns are followed by men with camera phones.

American popular opinion on Vietnam, “the first television war,” was heavily influenced by the fact that the horrors of the conflict were viewable on a mass scale, a scale that is now being dwarfed by the use of social media in the Arab Spring. But the sheer glut of information that is readily available for those of us distant from the conflict — tweets, YouTube videos, and blog posts — is perhaps not entirely beneficial to those who endanger themselves by providing that information. When it comes to news, we may immediately assume that more coverage and more perspectives are better, but volume does not necessarily ensure that we, as news consumers far from where the story is happening, are truly receiving an unbiased examination of events.

That we don’t hear about local press fatalities belies the notion, put forth by The Times 11 years ago, that we value journalists’ sacrifice because the sacrifice is a risk inherent to creating independent, unbiased reporting. This may be so, and a diversity of viewpoints is certainly essential to creating an accurate news narrative. However, the silent casualties of local press, of which the Syrian conflict is a good example, indicates that we don’t value journalistic sacrifices for this reason alone; we mourn losses in our press corps because they are our press corps, not because of the quality of journalism they put out or the risks they take in the field.

The term “Arab Spring,” for example, is representative of the highly constructed nature of corporate journalism, in any country. Writing for Al Jazeera, Joseph Massad described the term as being an attempt to steer the movement towards an American style liberal democracy by imposing linguistically on its “aims and goals.” “Spring” itself is a reference to the European Revolutions of 1848, which is referred to as the Springtime of the Peoples for the revolutionary movement away from monarchy and towards democracy.

With this type of deliberate linguistic and narrative architecture in place throughout mass media, in the strictest sense, the most independent, unbiased journalism being created now is the kind coming from Syrians with camera phones. Whatever their personal biases may be towards the conflict in their own country, that grainy footage and those of-the-moment tweets are unfiltered and unedited. The fact that foreign press casualties are not more publicized means that what we say about our own press casualties is merely propaganda; that it is not independent news we value, but news that fits into the constructed narrative, from journalists who have editors back home at their news conglomerates.