In early September, as the academic year settles in at the University of Toronto’s three campuses, a handful of students arrive at Pearson Airport, anxiously awaiting the start of their university careers.

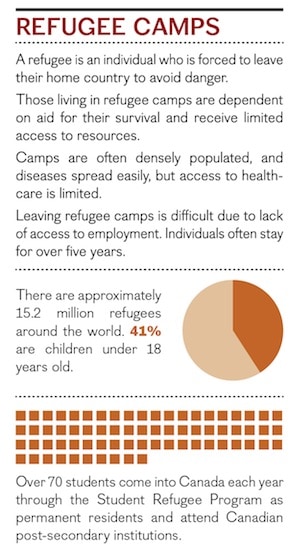

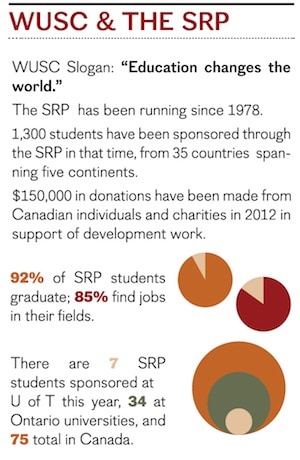

These students are refugees, sponsored through the collaborative efforts of the University of Toronto and the World University Service of Canada (WUSC). Since 1978, WUSC has helped 1,300 students from 35 countries across five continents attain their goal of higher education. Through WUSC’s Student Refugee Program (SPR), students are given the opportunity to immigrate to Canada and attend one of 61 participating colleges and universities.

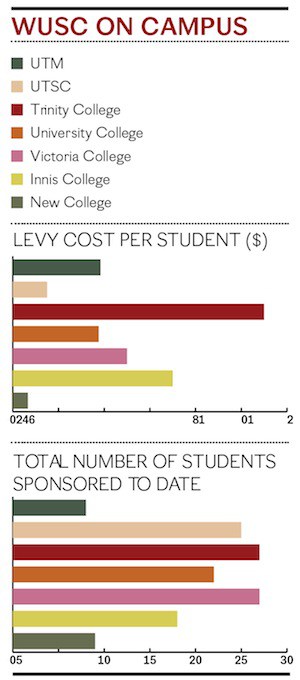

The University of Toronto sponsors the most students each year of universities in Canada. The University of British Columbia is the only other institution which also sponsors more than one student. WUSC local committees at U of T are run from University College, Victoria College, Trinity College, Innis College, New College, U of T Mississauga, and U of T Scarborough — each of which individually hosts a student.

In spite of its broad impact, WUSC is a little-known entity on campus. Many students are unaware of the role they play in supporting student refugees through the SPR. The SPR is made possible through the WUSC levy, a fund that each student at the university contributes to. The fee itself is nominal, but its reverberations for the refugee students are quite significant. The fees allow them to leave their countries of asylum and enter Canada as permanent residents in order to pursue an undergraduate degree, with assistance provided by the levy.

The journey to Canada

The WUSC students’ journeys begin long before they set foot on Canadian soil. WUSC only admits 70 to 75 candidates per year, and admission to the SRP is based on a lengthy and complex process. Students must achieve exceptional academic standing in high school, successfully complete an English proficiency test, and interview process.

The WUSC students’ journeys begin long before they set foot on Canadian soil. WUSC only admits 70 to 75 candidates per year, and admission to the SRP is based on a lengthy and complex process. Students must achieve exceptional academic standing in high school, successfully complete an English proficiency test, and interview process.

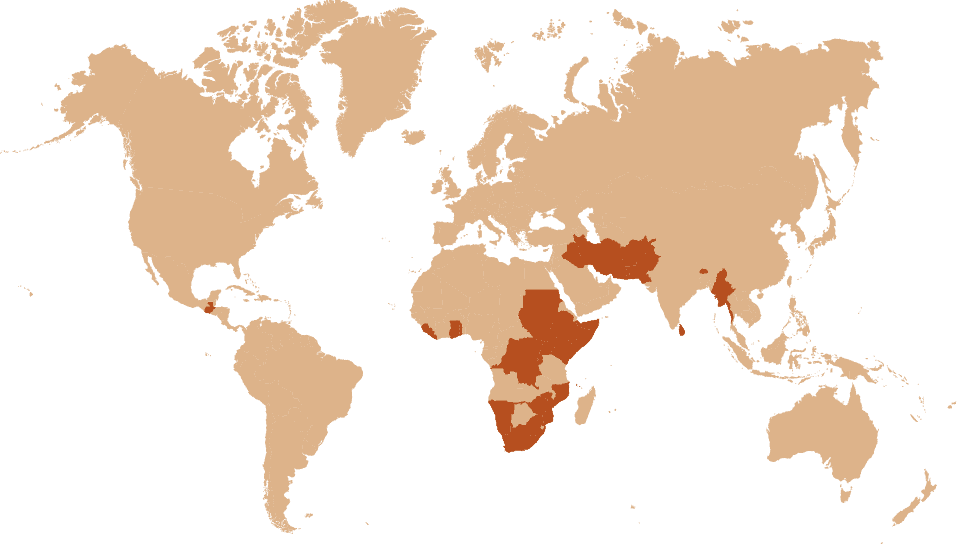

Upon acceptance, students journey from their homes to a participating refugee camp, where they begin a year-long orientation process.

“I was exempted from the orientation for security reasons,” says Chris Dominic, a second-year SRP student.

Dominic explains that, while she spent her childhood in Kenya, her family originates from Sri Lanka, so she “didn’t blend in” with the demographics of the Kenya-based camp. She adds that this put her at risk of physical and sexual violence.

For Iris, a first-year SRP student originally from Rwanda, participating in the orientation meant leaving her home and family for a 24-hour long bus ride to the nearest camp.

The orientation aims to build students’ skills and prepare them for the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) exam — which, along with an extensive research paper, plays a significant role in determining their sponsorship. Teachers also help students build skill sets essential for success at a Canadian post-secondary institution, including research methods and computer skills.

Dennis, a second-year SRP student, mentioned that many of the students also work in organizations at the refugee camp. Dennis and his family fled Rwanda when he was two years old to escape genocide, and eventually received asylum in Kenya. During his time at the refugee camp, he taught mathematics and biology to high school students.

Students also receive an introductory course about life in Canada. “Most of the things I was told were strange to me…terms like ‘double-double,’ ‘apartment,’ and ‘sublet,’” says Adam*, adding that the amount of information was often overwhelming.

The orientation year is accompanied by a sense of uncertainty. Students have no idea whether they will be accepted by Citizenship and Immigration Canada for permanent residence, or at which post-secondary institution they will be placed.

Christine Farquharson, the co-chair of the Victoria College WUSC committee, expressed that those involved with the program at the university often face much uncertainty ahead of the new academic year as well.

“Sometimes, you’ll know who your student is before everything has been confirmed with immigration, so you don’t want to get anyone’s hopes up, but you also want to give them a sense of what they’re flying off to,” she explains.

When the decision is finalized, a welcome package is provided to successful applicants, sometimes only days before the students must leave for Canada.

The good news is always surprising, says Iris: “No one is ever ready… I had to rush home [from the camp] for last minute shopping and goodbyes.”

Support systems

The SRP could not function without the dedicated students and administration who manage each local committee and secure the authorization for sponsorship.

The SRP could not function without the dedicated students and administration who manage each local committee and secure the authorization for sponsorship.

“It’s a moral and legal responsibility,” explains Caitriona Brennan, the coordinator for International Student Life at Victoria College.

By agreeing to sponsor a student, the local committees, like any immigration sponsor, take on a legal responsibility to provide a place of residence and financial support for the student. Planning starts well before the student’s arrival. Sarah, Trinity College’s student refugee coordinator, explains that preparations entail, “….filling out various forms, shopping for all the basic necessities,” and the task of setting up the student’s room.

After several months, the students arrive at Pearson in early September.

Brenna told the story of the arrival of the first WUSC student she mentored five years ago; “I had just started this job, and had no idea what WUSC was coming into it. I was told I had to pick the student up from the airport, and on the way there I was worrying myself sick about how to greet them — whether to hug, or shake hands — and then people started coming out, and suddenly this very tall man was standing in front of me and he gave me this huge hug. It’s an incredibly special moment.”

The committee directors and members are protective of their students. Their goal is to ensure the transition to Canadian life goes as smoothly as possible, which includes allowing the student to integrate into the campus without an affiliation to the WUSC organization.

“They’ve been through a lot, depending on where they’re from and their background, and it’s a fine line we walk between giving them privacy and letting them lead an independent new life, and becoming involved in their backstories,” says Molly McGillis, the co-director of the UC committee.

This concern for the privacy and integration of refugee students is a central reason why WUSC is a relatively unknown entity on campus. Zoe Edwards, UC’s other co-director, also attributes the anonymity to instructions from WUSC to not sensationalize the students.

“The way that we see it is that our mandate is to sponsor this student, and to mentor this student. Raising awareness and advocacy is secondary to that core purpose,” adds Farquharson.

The mentors are deeply invested in the safety and comfort of their students and express overall satisfaction with WUSC as an overarching organization.

“I love the program,” says Melissa Theodore, vice-president external at the University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union, adding: “I feel like we could be doing so much more than bringing in one student each year.”

Farquharson explains: “It’s more than a club. You become the student’s support system, and we have to be sure that that support system will be there when the students need it.”

Building foundations in first-year

The first weeks after a refugee student’s arrival are hectic, as they and their mentors scramble to secure OHIP health coverage, finalize course enrolment, purchase a sin card and cell phone, and get oriented through campus tours.

The first weeks after a refugee student’s arrival are hectic, as they and their mentors scramble to secure OHIP health coverage, finalize course enrolment, purchase a sin card and cell phone, and get oriented through campus tours.

At the beginning of the year, the director’s role is a full-time job. McGillis explains: “We are there constantly during the first weeks as mentors. We walk them through budgeting, and set them up with a job at the registrar’s office for first-year. Once school starts, we keep in touch regularly. If they need winter clothes, or have to go to the doctor, we’re there.”

Building foundations for the student’s upcoming years in the city is the main goal of the first year of the SRP at U of T. Tuition, residence fees, and meal plan costs are all waived by the registrar’s office for this year, or are paid for through the WUSC levy, depending on the local committee. This is essential to the program’s existence, as the WUSC students are not eligible for OSAP until second-year. “The students come here with very little,” Farquharson explains.

A monthly stipend provides funds for a laptop and printer, winter clothes, and anything else the student might need in their first year, including callings cards to communicate with their families back home. The levy also pays off the sponsorship fees and immigration loan that the students take out in order to travel to Canada.

The relationships between committee members and students developed in this critical first year often grow into lasting friendships.

Farquharson describes, “[The experience] made me think about how I perceive the idea of mentorship, and it’s made me reevaluate it. It’s also changed the way I think about friendship.”

Often, WUSC students become involved with their local committee following their first year, sharing their wisdom with incoming students. “It makes me feel good to know that I can help a person who’s in the same situation as I was. I know how he’s feeling and I’m just glad I can help him out,” Dominic explains.

Overcoming obstacles

SRP students face significant challenges in spite of their excitement to study abroad. Their journey takes them thousands of miles from home to a new city with a harsh climate, a highly competitive academic environment, and considerable financial hurdles.

“The worst was having to leave my family. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” says Dominic. She tries to combat homesickness by Skype-calling home each week.

Weather is also a challenge. Iris shakes her head, noting that it “was fun at first to see the snow,” but it has since become far too bitterly cold for her liking.

Fabrice, a first-year SRP student, explains that it took time to adjust to the taxation system and the differences in the Canadian diet: “I’m used to the food now, and I’m loving it.”

While their sentiments are predominantly positive, the students have some suggestions to improve the program. Adam stresses the need for increased academic guidance. “When WUSC students arrive here, they sometimes have no idea what courses or programs they want to study,” he says.

Fabrice shares the same sentiment, describing the course selection process as “baffling.”

Dennis suggests that the timeline from submitting the application to receiving acceptance should be shortened: “The transition from high school to university, which is too long, becomes a challenge when [students] have to recap and use what they are expected to have covered back in high school.”

In their second year, SRP students qualify for OSAP to offset tuition and living expenses, and many continue to work on campus. They take a full course load, and work to pay for expenses that OSAP doesn’t cover.

“I am nervous about next year, but I look at all the other students who come here and survive, and I’ll just do what they do, and I know everything will be fine,” says Iris.

Some schools choose to sponsor a WUSC student every four years, and support them financially for the duration of their degree. When asked whether they would prefer this option, both Iris and Chris say they wouldn’t. “It’s better when they take students every year. That way, more students can benefit,” explains Iris.

Other students have only gratitude towards the program. “The WUSC experience has been the best thing for my academic career; they gave me a chance. The experience is definitely positive, I wouldn’t change a thing,” says Fabrice.

“Once in a lifetime”

The SRP is overwhelmingly successful, with 92 per cent of sponsored students graduating and 85 per cent finding jobs in their chosen fields. The WUSC levy makes the program financially possible, and the dedication of the students and mentors renders the experience and the outcome resoundingly positive.

Brennan says she often finds herself in awe of SRP students’ sense of purpose and willingness to give back. “In terms of having your perspective changed for the better, they really do make you pause. It’s their outlook, their sheer gratefulness for so much, things which most of us take for granted,” she reflects.

Dominic explained that she sends a portion of her paycheques home to her younger brother in Kenya to help finance his education.

The little-known WUSC program, if discussed more openly on campus, has potential for a local impact beyond changing the lives of the students who participate in it, as it brings other students in the U of T community together in support of the common pursuit of equal access to education.

Dennis reflects: “Making the decision to come to Canada was the easiest decision I’ve ever made… I miss home… but this opportunity is one that comes once in a lifetime, and I’m glad I took it.”

*Name changed.

Some last names in this article have been omitted at the request of the interview subjects.