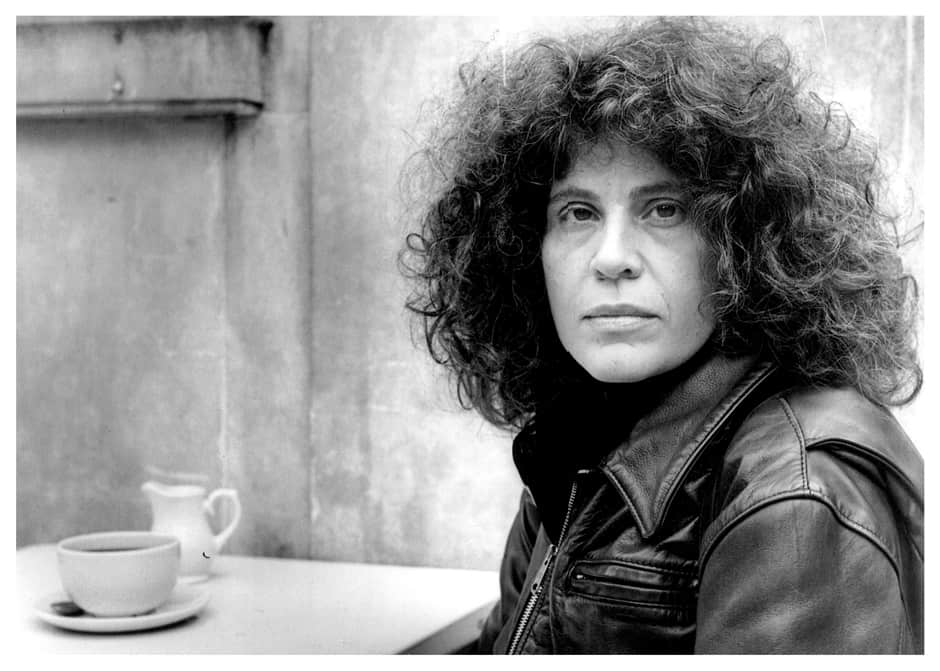

Anne Michaels first gained acclaim for her poetry with her first collection The Weight of Oranges, released in 1986. Her eloquent manner of speech makes interviewing her not unlike engaging with a literary text.

With five poetry collections and two award-winning novels under her belt, Michaels is arguably one of the most recognizable female Canadian authors alive today. Yet when I spoke with her, the experience quickly became a warm conversation between a student and a mentor. This is likely due to Michaels’ recent experience offering one-on-one writing consultations for University College students in her role as this year’s Barker Fairley Visitor.

“It’s a great opportunity to talk about what you’re doing, what you want to do, express your frustrations — just to think of strategies for how to proceed if you really want to write,” explained Michaels. She described students bringing in a laptop and showing her a file, or reading aloud.

“I’m very moved by the honesty and commitment that I’ve seen so far, and the desire to really explore certain things that may be difficult,” she said. “I always stress that you’re writing for yourself, but that when you have something to say write from the core of you, because it’s usually very useful and welcome to someone else.”

Michaels herself started writing from a young age, and credits that with her success as a writer: “I was very lucky to have that passion from childhood. The rest is hard work — many years of apprenticeship. I think people are hard on themselves, they want to be perfect immediately, and that is impossible, language will never allow us to do that. It’s going to take us a long time to understand the how and the why of it.”

Equally important to constant writing were the authors she read as she grew up and entered post-secondary education. “Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy, Keats, Austen, Dostoyevsky, all the great names you would imagine — the greats,” reflected Michaels when asked which books impacted her the most. “A book will move us, push us to a place that we didn’t know we needed to get to, offer us a hand before we knew we needed it.”

When I expressed that I often felt daunted in the face of such figures, Michaels assured me that she thought this was a healthy part of the writing process.

“I think that intimidation is humility,” she explained. “I think that’s a really healthy thing, because it helps us understand that what we want to do is maybe bigger than we are. It will mean that you’ll stretch yourself beyond what you thought you could do. These are with the books that we need — we don’t need another easy read, we’ve got plenty of those. The book that really opens you, turns you inside out, those are rare, and that’s worth striving for, worth being intimidated about.”

Michaels’ writing advice stems from the idea that we should give ourselves permission to write, and write everyday. “Give yourself permission to sit there — often you have to justify it to yourself, because there’s so much going on in your day and so much going on in your life, how can you carve out a time where you can sit there and say it’s for you? But, it’s that tiny little bit of space where you’re saying ‘I’m going to do this everyday,” she said. She explained that even taking the time to write 15 minutes everyday will add up very quickly, and the more you get used to the process of writing the longer you’ll be able to do it for!

When asked about the idea that writing is a selfish act, something that primarily results in self gain, she said, “It’s very ironic because writing is not easy — writing is difficult, writing is humiliating in a lot of ways. But I guess there’s a part of our brain that says, well it’s not earning money, it’s not doing this, it’s not doing that, what do I have to show for it? You get into a morale of ‘I’ve got to get published, I’ve got to send stuff out,’ and that’s going to confirm me and what I do, when in fact the writing itself is what must confirm you. Not the business of it, it’s the doing of it.”

When asked about why she chose to begin her writing career with poetry, Michaels stated she was focused on the idea of being able to express a single thought: “The language, the desire to try and set something down with absolute simplicity and clarity. To name a moment that would otherwise not be named.”

She then moved to the form of the novel because poetry “could not contain what I was attempting.” Michaels explained that for her, novels always begin with a cluster of questions of “haunting philosophical questions.” Michaels’s novels have been rooted in history — Fugitive Pieces follows the life of Polish poet Jakob Beer during and after the Holocaust, and her subsequent novel The Winter Vault told of those trying to save an Egyptian temple in the 1960s.

The main question that haunts Michaels, she says, is: “That there’s nothing a man won’t do to another, and nothing a man won’t do for another… When you’re going into territory that’s difficult or perilous, territory we may naturally want to turn away from, it’s an incredible privilege to have a few hundred pages in the company of a reader, so that you can bring yourself and the reader very close to the center of certain questions. A novel lets you do that in a way that poetry just can’t. It’s a question of having time with the reader, and time with yourself, to get very close to the heart of something. These are the questions without answers, the ones that you keep asking in different ways.”

Michaels’ most recent work is a poetry collection, Correspondences, which was released in 2013 and was shortlisted for the 2014 Griffin Poetry Prize. Correspondences features a single poem, that can be read at any point. The book that holds it is accordian in style, with compelling portraits included within, allowing the reader to choose a point to begin from, and mix and match a portrait with a portion of the poem.

“What has to happen, and what is already happening, is that the book is seen primarily as an object,” she expressed. “The physicality of the book will once again become the focus, and books will be cherished for being more and more beautiful. We’re going to come to understand the value of holding something in your hand.”

When asked if she sometimes feels confined to the category of “female Canadian author,” Michaels said laughingly, “That’s also something that I think can be put on women writers. A man is considered chivalrous or discrete, while a woman may be considered secretive — there’s a real double standard there.” She continued: “I think everyone has a tendency to categorize things, in order to make sense of the world. But yes, that is a [category I am subject to], and I’m always trying to subvert that.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.