Some students are dissuaded from pursuing a subject area that they enjoy by the possibility of receiving low grades. Our current grading system is antiquated and does not provide a legitimate evaluation of individuals. Rather, it represents a flawed method by ranking students in a standardized mold of institutionalized education.

Unfortunately, the free and compulsory education system North Americans grow up in cannot trace its ideological roots back to an altruistic government interested in promoting open discussion, debate, and free thought.

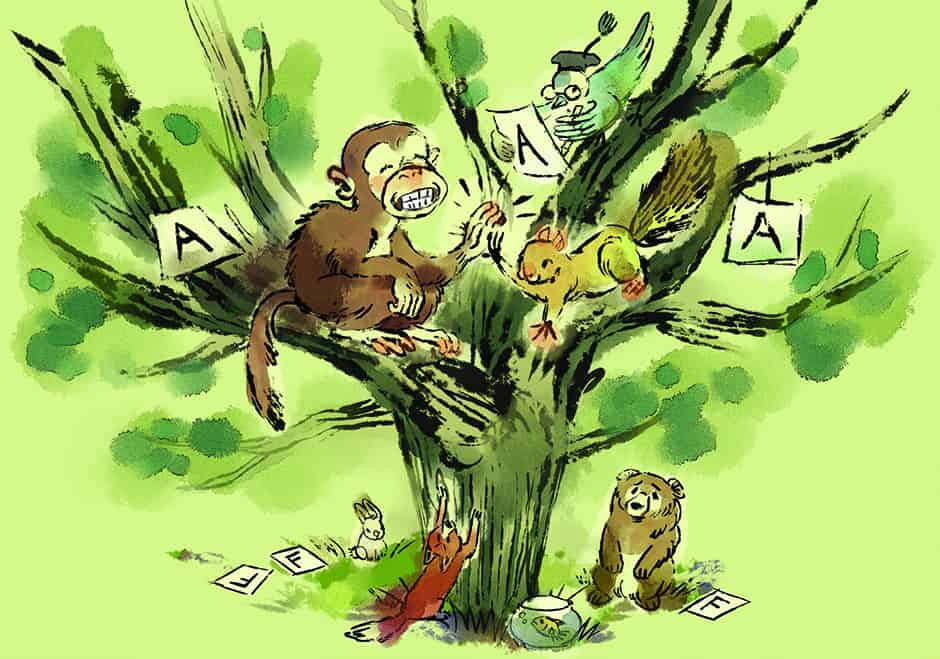

Learning can be one of the most inspiring and rewarding activities in life. So why do most people equate learning with boredom and monotony? Why is it that many children fake being sick to avoid going to school? By and large, institutionalized education fails to accommodate people’s idiosyncrasies, such as different learning speeds, socio-economic situations, learning styles, or personality types. It is a one-size-fits-all approach to learning, which all too often teaches students to memorize rather than think for themselves.

For example, the normative grading system used in North American universities sets a distribution of grades before the semester begins, thereby preemptively categorizing students. Professors aim for their class averages to be within a range that shows that the course is neither too easy nor too hard. This system is not about creating a positive learning experience, nor a personal one — students are often graded on a relative scale, rather than one that accurately evaluates their individual performance.

The traditional grading system teaches students to be overly competitive at a time when society desperately needs its best and brightest to work cooperatively and collaborate to find solutions to pressing issues, from cancer research to global climate change. The current model demoralizes individuals by labelling people subjectively with letter or percentage grades that reflect little about an individual’s ability or value beyond their basic capacity to memorize and regurgitate. Grades can cause students to become extremely stressed, when education should generate excitement.

What’s more, institutionalized education places an inordinate emphasis on weighted exams, wherein students are called upon at the end of every semester to collectively spew what they can remember from the syllabus. Realistically, exam results more accurately reflect an individual’s ability to work within the format of the test than they do a student’s ability to think critically. Students are often required to memorize facts that will change over time, like the population of a city. The grading system does not usually reward students for relating course material to relevant topics or issues from sources outside of the curriculum. Clearly, exams in this format do not measure one’s ability to analyze, but rather to memorize.

Of course, any condemnation or criticism of our current system of evaluating students must go hand in hand with a thankful appreciation for all that is right and good with modern education in North America. Many countries have little access to educational resources and high-quality teachers. In that way, we are truly privileged, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for progress.

As students, we all have so much potential that is too often undervalued or glossed over by institutionalized education. Don’t let your grades define you. Free thought is of more value than any marks, degrees, or professional titles that you acquire. It is time to shed these old values and antiquated systems in favour of a method of learning that allows for more autonomy, enjoyment, and fulfillment.

With the emergence of open source learning platforms, the advent of technology, and increased access to the Internet worldwide, traditional educational institutions may become unnecessary. Hopefully, U of T will be able to keep up with these advancements and adapt to emerging values, lest the institution erode slowly into obsolescence.

Karlis Hawkins is a third-year student at Trinity College majoring in geography and environmental studies, with a minor in political science.