Ruben’s* apartment looks a lot like mine. Unframed posters adorn his walls and empty beer cans litter the countertop — it’s a typical student living space. But one thing’s patently different: on Ruben’s coffee table sits a twenty-inch water bong, stained with resin from the countless tokes that Ruben and his friends have taken from it.

Ruben reaches for the bong as I sit down to talk about his marijuana use. He’s a U of T student on hiatus: his active student status was suspended for poor academic performance last summer. And, yes, he says, his weed habit did have a lot to do with it.

But Ruben says he’s critical of his drug use and is aware that it has both a positive and negative effect on his life. “It helps me relax,” he tells me, in between cracks directed at LeBron James’ choice of hairline on the television in front of us. “There’s still the fun factor, the excitement factor. But if I’m ever in pain I don’t need to take an Advil. I don’t need sleeping pills. It helps with anxiety because it calms me down.”

Yet he acknowledges that these benefits are countered by the negative effects of the drug. “[Smoking marijuana] also makes me forget about the things I need to do, which can be good or bad… It’s all about time and place,” he says.

A HARMFUL MENTALITY?

Cannabis use is relatively prevalent in Canada, with one in five individuals aged 15 to 24 indulging in 2011. It’s usually smoked and sometimes eaten. The effects of cannabis range from mild euphoria to pain relief to, in rare cases, acute psychosis and delusions.

Youth tend to think of cannabis as largely harmless and natural. A 2013 Canadian Centre On Substance Abuse (CCSA) survey noted that young people believed cannabis promoted relaxation, focus, and creativity. Some of those interviewed also tended to see any long-term negative effects, such as cognitive decline or dependence, as a defect of the individual rather than the drug itself, and even these concessions were often overshadowed by beliefs in the substance’s medicinal properties. Some even thought pot could cure cancer.

Not since the days of Reefer Madness, it seems, has cannabis been approached with hysteria or contempt. Most young users today seem to get blitzed without much concern about the drug’s potential dangers. The CCSA survey suggests that many students — Ruben included — see pot as something that can be used moderately to only minor detriment.

Not since the days of Reefer Madness, it seems, has cannabis been approached with hysteria or contempt. Most young users today seem to get blitzed without much concern about the drug’s potential dangers. The CCSA survey suggests that many students — Ruben included — see pot as something that can be used moderately to only minor detriment.

But Dr. Wiplove Lamba, an addictions specialist at St. Michael’s Hospital, believes this attitude does not reflect the reality of cannabis use. “There are problems with the medicalization of marijuana,” he says. “Students don’t think it’s harmful. When people think something is not dangerous they tend to use it more. Some patients might say ‘I can’t sleep or eat without marijuana’, but what they might not realize is that these can be signs of dependence,” Lamba explains.

“Some people think the big bad government is preventing people from smoking weed, but there are risks. There needs to be more information… There is little data on what cannabis does to the body… So there are no low-risk guidelines for use, like we have with alcohol,” he adds.

A 2013 Health Canada report acknowledged that cannabis impairs short-term memory, attention, and concentration, among other faculties. This damage, it notes, “[has] the potential to be long-lasting”, and even quitting for a year or more did not restore cognitive function for those who started smoking pot in adolescence. Perhaps one of the strongest indicators warning against youth cannabis use comes from a study done in New Zealand, which found in heavy users — after following over a thousand participants for 25 years — an average decline of eight IQ points.

Lamba considers the New Zealand study “as good as you can get science-wise”, and recommends that marijuana not be used by anyone before the age of 25, as the frontal lobes have not fully developed until then. This not only means that youth lack the requisite gray matter to fully weigh the risks of their actions, but also that the cognitive effects of cannabis can permanently alter the course of neural development.

“For me personally this study would be enough not to use [cannabis], but everyone has to make their own decision,” he says. “What’s concerning is that in adolescents, it’s not a reversible effect.”

USE MANAGEMENT

So far, these findings only show the impact cannabis might have on a student’s academic performance. But mental health and social functioning are also at risk. Marijuana increases the possibility of developing schizophrenia. Additionally, its illegal status can also lead to serious social repercussions such as stigmatization — not to mention the possible criminal consequences of its possession, cultivation, or sale.

Yet the Health Canada report also suggests that weed might help anxiety, lending support to anecdotal claims like Ruben’s. Hunter*, a fourth-year history major, spoke about a similar experience with cannabis, claiming that his daily use allows him to cope with academic tasks by alleviating his anxiety. “I smoke every single day, at least once,” he says. “If I have papers and shit to do then I’m smoking all day at home. I sit there with my bong on my table and just work all day [high].”

I express my surprise that he can work while stoned, as it’s not known for increasing attention spans. “I’m not sure if it helps me focus,” he responds, “but it’s definitely a coping mechanism.” Hunter elaborates that it makes him feel guilty to rely on marijuana to help him with daily tasks, but he compares it to coffee, characterizing cannabis as a substance that can expedite certain activities.

“One thing I’ve noticed is that it really does vary from strain to strain,” he adds. “I used to be like, ‘oh, if it’s green I’ll smoke it’ but now I think, no, that doesn’t work… I use a vaporizer and I find for medicinal qualities it gets you exactly what you want. You set it on the temperature that you want the specific chemical to be vaporized at and then you get always that. It’s pretty technical. Like, if you want to medicate for anxiety you set it at 170 [degrees Celsius].”

“One thing I’ve noticed is that it really does vary from strain to strain,” he adds. “I used to be like, ‘oh, if it’s green I’ll smoke it’ but now I think, no, that doesn’t work… I use a vaporizer and I find for medicinal qualities it gets you exactly what you want. You set it on the temperature that you want the specific chemical to be vaporized at and then you get always that. It’s pretty technical. Like, if you want to medicate for anxiety you set it at 170 [degrees Celsius].”

Hunter tells me that weed helps him manage his anxiety better than pharmaceuticals, allowing him to avoid prescription anxiety medications such as Ativan, which he tried after seeing a doctor about his symptoms. “I did Ativan twice and it made me feel like I didn’t have a soul for a day afterwards,” he says. “I felt like I was just empty. Fuck that stuff.”

From talking to Ruben and Hunter, it seems as though use management would become easier if cannabis were a regulated substance. “Tailored” highs, a result of knowing the chemical structure of the strain prior to consuming it, could act as a preventative measure against some of pot’s more worrisome effects.

Jane*, a fourth-year humanities student, radio show host, and editor of a student journal, also views cannabis as the best way for her to manage her mental health. “I smoke it for a number of reasons, one being my depression,” she says. “I use it as an alternative to bottled prescription medication. I have nothing against that kind of treatment, it’s just not for me. [Smoking weed] pretty effectively helps me deal with my depression. I’m a lot happier with weed in my life than without it.”

I ask Jane if she thinks her gram-a-day habit has impeded her academic success. “It’s really hard for me to say whether or not I’d be more successful had I never smoked pot,” she replies. “On one hand, I understand the link between memory and marijuana use; sometimes my reaction time is a little slower than it should be in terms of critical thinking. Being someone who uses it in part to deal with depression… I’m gonna have to say no, I probably wouldn’t be able to get out of bed and do my thing every day without it.

“I’m not saying weed ‘saved my life’ or anything like that, I’m just saying that it helps me calm myself down and not freak out about everything,” she adds. “It’s a good way to unwind. It makes me less intense.”

“I’m not saying weed ‘saved my life’ or anything like that, I’m just saying that it helps me calm myself down and not freak out about everything,” she adds. “It’s a good way to unwind. It makes me less intense.”

It would seem that at least some students at U of T can smoke pot regularly and still function — in some cases, perhaps better than they would if they didn’t use marijuana. But Lamba points out that marijuana’s criminal status, and its lack of experimental data, currently precludes an informed way to regulate one’s use. “If there are benefits to [self-medication] they have to be judged on an individual basis,” he says, “although I think some medical body could [plausibly] come up with low-risk usage guidelines.”

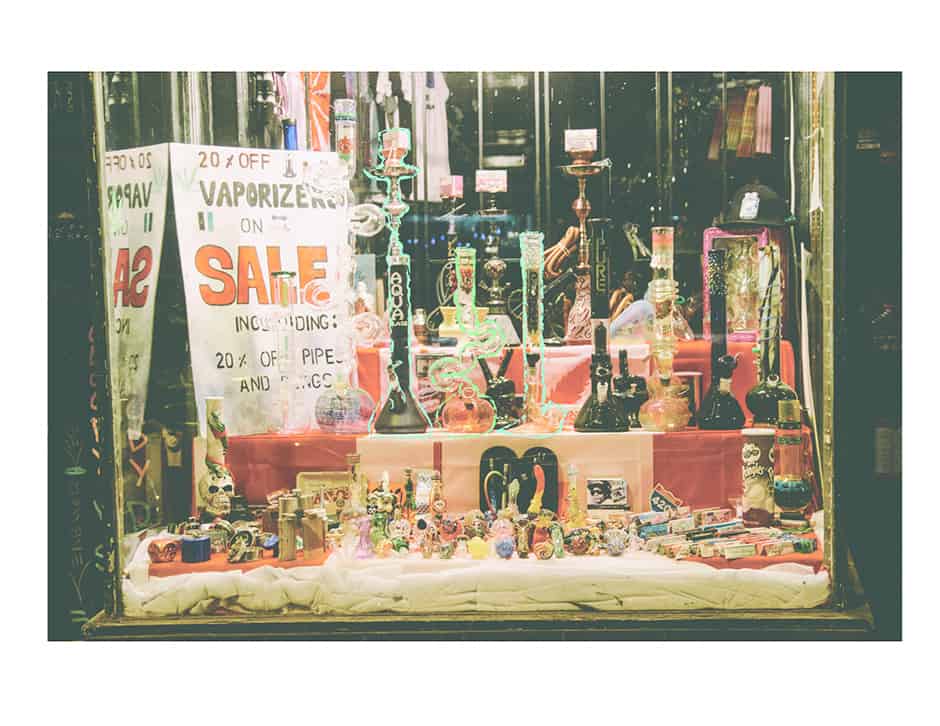

The medicalization of marijuana has been a hot topic in Canadian politics for the last few years. Compassion centres currently exist to supply those who were deemed eligible for cannabis treatment by a doctor, but the government has not actually approved its use as a medicine. Rather, court rulings have enforced reasonable accessibility to the substance for patients who require it. Cannabis effectively treats a slew of ailments, including chronic pain, nausea associated with chemotherapy, and depression associated with chronic diseases.

“I’m not for criminalization of this drug at all,” says Lamba. “But the problem with medicalization is the delivery system [smoking], and we have no way to determine the dose being used. Health Canada made [medical marijuana policy] without consulting medical bodies. I think decriminalization is inevitable but there are challenges.”

CANNABIS CULTURE, NORMALIZED

In 2011, sociologists at U of T conducted a survey on the relationship between recreational cannabis use and academic performance. They found no association between recreational users and bad grades, indicating that marijuana use was “normalized” at U of T. In other words, most of the students surveyed were able to smoke pot without the drug hurting their studies.

The researchers suggested that while high school users — who typically show a correlation between cannabis and poor performance — were often part of a deviant, low-achieving subculture, university users were “sufficiently academically focused” to regulate their usage and escape the negative effects that befell their younger counterparts.

Kristen*, a PhD candidate at U of T and pro-legalization advocate, agrees that recreational use is becoming more prevalent and acceptable. “We are seeing a normalization of cannabis use, where even if we don’t use cannabis we can walk into a party and see our friends doing it and we’re okay with it,” she says.

Kristen*, a PhD candidate at U of T and pro-legalization advocate, agrees that recreational use is becoming more prevalent and acceptable. “We are seeing a normalization of cannabis use, where even if we don’t use cannabis we can walk into a party and see our friends doing it and we’re okay with it,” she says.

I tell Kristen about the students I’ve spoken with, who consider their weed habits a means of self-medication. In contrast to Lamba, Kristen supports the idea. “On a scale of relative harm and risk cannabis is relatively low,” she explains. “Once it gains legitimacy as a medicine it I think it will be accepted as an alternative to pharmaceuticals like Ativan to treat conditions like anxiety or depression.”

“[Cannabis] doesn’t get as much attention [as pharmaceuticals] but it’s equally important for its medicinal benefits,” she adds. “It’s not as harmful as a lot of pharmaceuticals we reach to, like Ativan.”

However, cannabis is still a physically addictive substance, with nine per cent of users developing dependency. Dr. Lin Fang, an associate professor at U of T’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, warns that cannabis’ increased potency might mean a greater risk for addiction, and that “cannabis use is associated with a range of mental illness, such as anxiety, psychosis, and depression.” Self-regulation of use is difficult, she says, because “we do not really know what [a] moderated amount is for each individual.”

DEALING WITH DOPE

Cannabis’ potential as a substance that can both help and harm makes informational resources at U of T essential—but these resources don’t currently seem to exist. Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), U of T’s notoriously overbooked therapy center, does not visibly address pot use aside from a single document on its website, and no external sources are available for students seeking information on marijuana.

“I do think it would be a good idea if we can have more resources designed for students,” Fang says, “that summarize the current research [evidence] in a user-friendly way so that students can make informed decisions.”

Lamba, Fang, and Kristen all see decriminalization as the best means of harm reduction. This sentiment echoes a 2014 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) report, which proposes legalization to address the failings of prohibition.

Lamba, Fang, and Kristen all see decriminalization as the best means of harm reduction. This sentiment echoes a 2014 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) report, which proposes legalization to address the failings of prohibition.

“Legalizing the substance together with tight regulations [such as] clear information about the product and its potency, minimum age… and education on the effects of cannabis is probably a more sensible way to go,” says Fang.

Kristen agrees, and encourages students to support legalization, whether they use cannabis themselves or not. ”Youth voices are integral to policy making, particularly with regards to drug policy,” she says. “Young people should have a say in how our policies are created and have access to information that lets them critically think about the policies they’re getting.”

As with responsible alcohol use, it seems as though students can smoke weed without necessarily harming their performance. But even for stoners like Ruben, indulgence needs to be carefully watched.

“Is what I’m doing bad? When you smoke a lot, you’re not happy with yourself,” he says. “It’s not for everyone. We live in a society where it’s regulated for reason.”

“Weed didn’t kick me out of U of T. I did,” he says, hitting the bong again. “You just have to learn to control it.”

*Names changed at students’ request.

Editor’s note (March 24, 2015, 12:02 pm): A previous version of this article contained the name of a source whose name is now omitted upon request of anonymity.