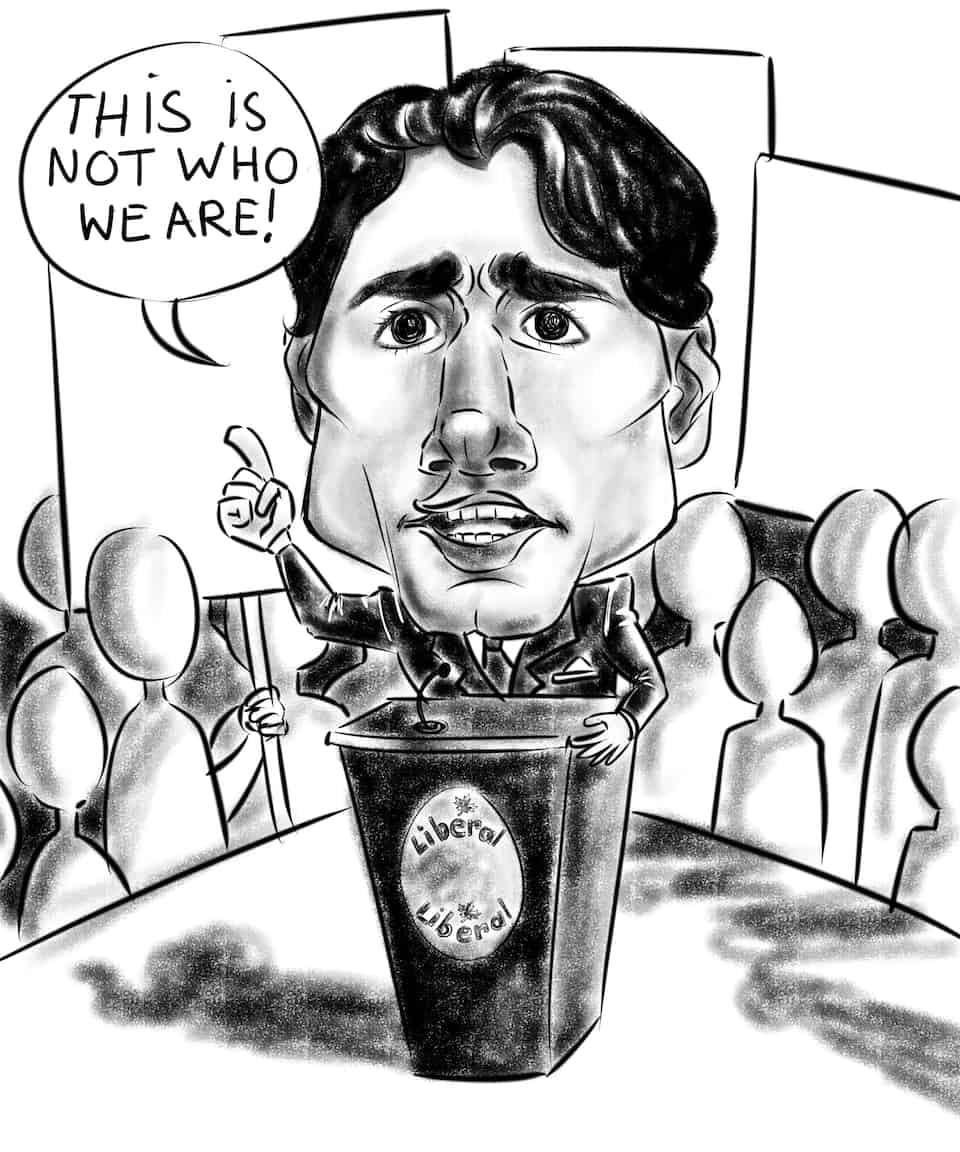

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Canadian media has emphasized our country’s warm welcome of Syrian refugees, as well as our rejection of the fear and bigotry that characterize conversations about refugees elsewhere in the world. In a similar vein, after the pepper spray attack on Syrian refugees during a welcome event in Vancouver earlier this month, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau responded on social media: “This isn’t who we are – and doesn’t reflect the warm welcome Canadians have offered.” His remarks show the way in which the discussion of refugees has been dominated, sometimes unhelpfully, by the language of Canadian patriotism.

This rhetoric does have value, especially in affirming newcomers’ sense of safety and belonging as they start their lives in Canada. A man who was hit in the pepper spray attack, Youssef Ahmad Al-Suleiman, told The Globe and Mail that, to refugees leaving behind political instability in their home countries, Trudeau’s clear and immediate condemnation of the violence is a meaningful gesture. Still, the public response to the Vancouver attack, which mirrors Trudeau’s comments leaves little room for exploring nuanced approaches to racism and Islamophobia in Canada.

It is comforting but not entirely accurate to claim that exclusionary violence “isn’t who we are” as a nation. Compassion and respect cannot be called inherently Canadian qualities any more than intolerance can. While Canada ha stated a commitment to advancing human rights, Canada’s history is marred by the legacies of Japanese internment camps, immigrant exclusion acts, and the residential school system, among other institutions of racial discrimination.

If the majority of Canadians today value compassion toward and acceptance of refugees, it is not because of the example of our national history, but in spite of it. Recent violence motivated by racism and Islamophobia, although committed by a minority of Canadians, shows that bigotry is still alive and well in Canada, often very close to home, whether or not we represent bigoted acts as Canadian, or acknowledge their place in Canadian history.

In the last few months alone, a mosque was set on fire in Peterborough; several incidents were reported in the Greater Toronto Area of Muslim women being harassed or assaulted in public places; Muslims were asked whether they were sorry for the Paris attacks; and a Muslim U of T student was spat on and harassed outside Robarts. This is to say nothing of smaller-scale acts of bigotry that often go unnoticed or are trivialized in classrooms, online comment sections, and other daily interactions, which Iris Robin noted in The Varsity last week.

Characterizing inclusion and compassion as essentially and even uniquely Canadian qualities is of limited value in uncovering the roots of racism in Canada and reducing violence and bigotry in the future. We have no hope of addressing the problem if we cannot acknowledge it first.

By writing off violence against refugees and racialized people as isolated incidents, and not representative of Canada as a whole, we risk minimizing the real threat of violence many Canadians face on a daily basis. If we are committed to making our campus and our wider communities safe and welcoming to everyone, refugees or otherwise, then we must commit to conversations about racism and bigotry that move beyond simple characterizations of Canada as an almost universally accepting place.

Language matters; let us be clear, direct, and honest in articulating the values and commitments we hold above all else. We welcome refugees into our communities today not because it is the Canadian thing to do, but because it is right. In the same way, we must condemn attacks against refugees not because these acts are un-Canadian, but because they harm real people, reduce refugees’ humanity, and violate our shared commitment to building a just and equitable world.

Rusaba Alam is a third-year student at Victoria College studying English.