Comedy has long been a forum for the crass, the vulgar, the indecent, and the shocking. As a result, comedians have been exempt from the rules of comportment by which we expect public figures to abide. The forthrightness of a comedian’s objective allows us to lower our guard: the comic isn’t convincing us to buy a product or support a candidate — they’re just someone on a dark stage trying to get a laugh.

But what happens when the laughter turns into gasps or jeers? It can be difficult to parse these types of incidents, which seem to recur every few months. Why do some so-called ‘edgy’ or ‘offensive’ jokes get laughs while others are endlessly dissected and editorialized until the comic is forced to apologize?

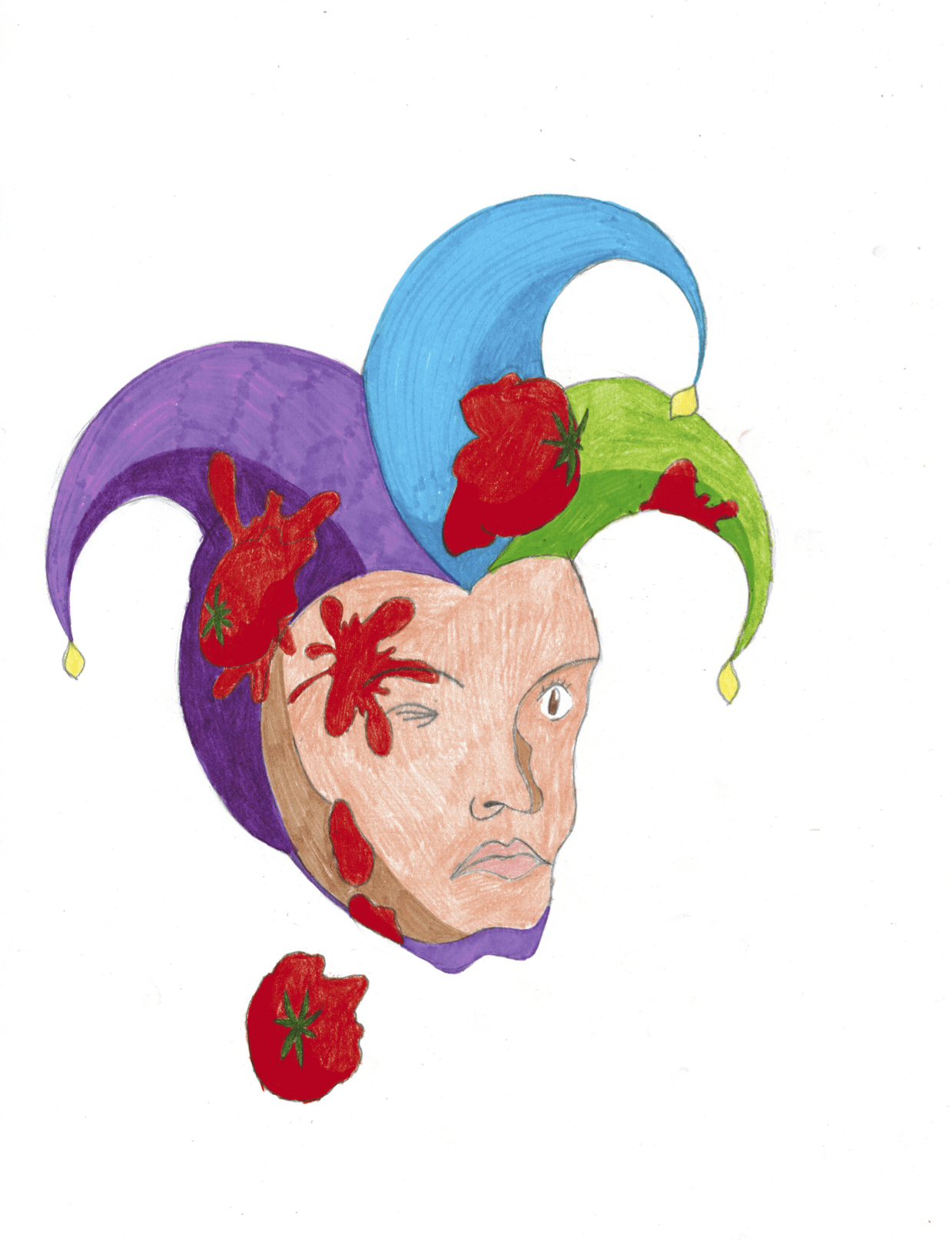

Comedian Kathy Griffin recently faced a tidal wave of backlash for a photo in which she appears to be presenting Donald Trump’s decapitated head, bloodied and grotesque, to the camera. Though Griffin intended for the stunt to be a joke, it received little support; it was instead condemned as tasteless and crude.

Griffin is hardly the first comic to be accused of crossing the line. In a 2015 Saturday Night Live performance, Louis CK joked that the legal and social price paid for pedophilia is so steep that “you can only really surmise that [child molestation] must be really good… for them to risk so much.” Within minutes, the internet predictably ignited with opinions divided between condemnation of the material and praise for CK’s willingness to tackle such a taboo subject on such a big stage.

In this instance, however, support was far more widespread for CK than it was for Griffin. While there was some backlash, there was a counterweight of support that Griffin did not find. The Guardian even published a piece complimenting CK for a joke that “expresses a level of complexity around that topic that is rarely seen” and for “[using] humour to confront difficult topics.”

The discussion about when comedy deserves condemnation exists within a larger discussion about political correctness and free speech. As frustrating as the seemingly constant outrage-punditry-apology cycle may be, berating an audience to ‘toughen up’ or ‘learn to take a joke’ doesn’t accomplish all that much.

Griffin promptly apologized for her misdeed in a brief video, and in doing so, she inadvertently revealed the nature of the distinction between CK’s joke and her own. Among concessions that the image was “too disturbing” and that she “went too far,” she said one key thing: “it wasn’t funny.”

Here, Griffin hit upon the crucial difference between her scandal and that of CK: though the former wasn’t funny, the latter was.

CK’s comments had substance, sharpness, and a little bit of truth to them. They made us consider the shade of grey in an issue that most would rather remain black and white. Alternatively, the Griffin photograph was just rude for rudeness’ sake. There’s nothing clever or interesting about it: it raises no issues, and it prompts no questions. It’s just a dead Donald Trump.

Of course, what is or isn’t funny is entirely subjective. But the important issue is not whether a punchline conforms to some abstract definition of ‘comedy.’ The audience’s understanding of and reaction to the joke is enough to push the needle between support and condemnation.

This matters because in comedy, consequence is king. The intention of a joke is just not salient if the audience understands it differently. Confronted with an underwhelming reaction, the stand-up doesn’t pause to explain to audience members why they should, in fact, have laughed at the joke they were just told. The audience either reacts, or it doesn’t. This distinction, arbitrary as it may seem, is the reason CK was able to come back and host SNL again earlier this year, whereas Griffin was fired by CNN from her yearly gig hosting New Year’s Eve Live.

We understand comedy to be an area in which controversial subjects can be openly discussed. This is not because some governing body has decided so, or even because of the long tradition of edgy and controversial comedy. Rather, it’s because the nature of the medium itself causes us to approach difficult problems in new ways and to expand our perspectives. When we can laugh at something, we can understand it in a new light.

This willingness to engage comes from us, but it is only triggered if what we are hearing feels like comedy — that is, if the jokes are funny. Comedians are not immune to backlash, but a joke is a unique opportunity to approach a complex issue in a novel way. This is what the CK joke achieved, and where the Griffin stunt fell short.

CK uses his comedy as a trojan horse. In a setting that is comfortable, relaxed, and even lighthearted, he compels his audience to consider an issue that is troubling and complex: human sexuality is complicated, and people who experience the urge toward pedophilia are likely just as horrified by it as we are as observers. In its capacity to create these insightful moments, comedy is unique.

Not just any sort of boundary-pushing qualifies as humour. Eddie Murphy begins his classic special Delirious by warning the audience that “faggots aren’t allowed to look at my ass while I’m onstage.” I don’t think that joke is particularly funny, but it’s not because the word ‘faggot’ disqualifies it right off the bat; in another context, that kind of language might make for a brilliant satirical routine. But Murphy’s reference, like Griffin’s, is just tired: it feels dated, ignorant, and naïve.

Over thirty years later, contrary to what people may believe, edgy comedy is still widely appreciated — it’s just that the edges have shifted. It seems that it is nearly always the audience’s responsibility to be thick-skinned, though it should be the comedian’s responsibility to understand their audience and create a show that is both enjoyable and challenging. Nothing is strictly off-limits. Any kind of joke about any subject imaginable is on the table. Just as long as it’s funny.

Zach Rosen is an incoming second-year student at Trinity College studying History and Philosophy.