… my cry of “Jane, Jane, Jane!” at her

window had altered the book for good.

— The Eyre Affair

The author of the Nursery Crime series, as well as The Last Dragonslayer and Shades of Grey, Jasper Fforde remains best known for his first string of books, that recounting the adventures of literary detective Thursday Next. Starting out in 2001 with The Eyre Affair, the series is now into its sixth novel, the recently released One of Our Thursdays Is Missing.

It’s indicative of Fforde’s range as a writer that the Thursday Next books have won both the Dylis Award for mystery and the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for comedic writing.

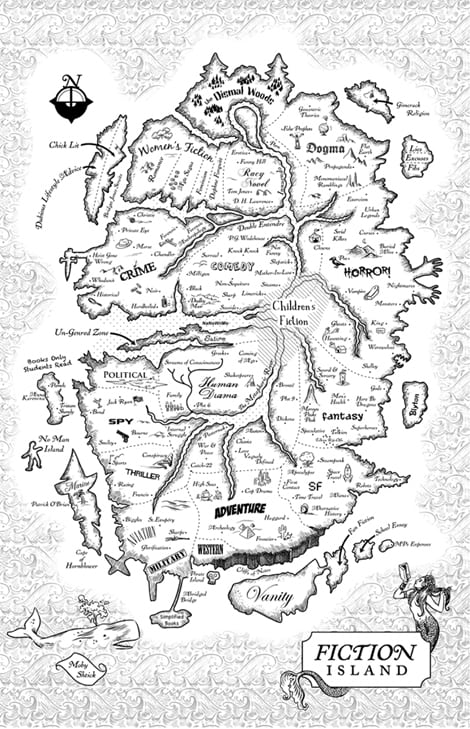

His books defy categorization (try finding the comedy-fantasy-crime-literary section of the bookstore), and Fforde himself has derided generic classification as “the measles of the BookWorld.” (For those unfamiliar with BookWorld and the rest of the Nextian universe, here’s a cheat sheet.) It comes as something of a surprise, then, that the map in the opening pages of Fforde’s newest work show Fiction Island divided by genre — but more on that later.

from One of Our Thursdays is Missing; enlarged view here

Fforde has said his first film script “was a mixture of Brazil, Hitchiker’s, Star Wars, Dragonslayer, and Mad Max II, I think, with a bit of homespun nonsense thrown in.” Add some Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and a bit of Doctor Who, send that mix off to investigate a crime among the literary classics, and you’ve got Thursday Next. The nonsense is good fun even if the name Pickwick means nothing to you, though the stories also reward the English Specialist for having read “The Lady of Shallot.”

Jasper Fforde was born in 1961 in London, England. Author of highly literate novels he may be, but academically inclined he was not. Fforde’s formal schooling ended when he left at age 18 with a D grade in Art (his description). He hasn’t studied English in a classroom since he was 16 years old.

Instead of going to university, Fforde went into film, starting out by making coffee and photocopies, then working his way into the camera department, where he eventually became First Assistant Camera on such films as The Trial, GoldenEye, Entrapment, and Quills.

He started writing in his spare time in 1988, and wrote 6.5 novels between then and 2001, when The Eyre Affair became his first published book. Famously, he collected 76 rejection letters during that time. But to those who might see this as a sign that publishers can’t recognize genius when they see it, Fforde is quite clear that those rejections were well earned. Around the time of his first published work, the author vowed he would write a book a year for 10 years. So far, he’s kept apace.

Jasper Fforde writes his “books about stories and stories about books” from his home just outside Hay-on-Wye, Wales, where he lives with his wife and two young daughters. When The Varsity met with him for coffee in March, he thought the family was just about ready to get a dog.

———

THE VARSITY

For readers who might not be familiar with the series and are wondering if they can pick up this book having not read the others: Who is Thursday Next? Why are there multiples of her? What are these two universes where the book takes place?

JASPER FFORDE

This book probably more than any other is helpful to someone starting the series again, because I see it essentially as a spinoff book. My major character, Thursday Next, works for a policing agency inside the BookWorld, which is the conceit for the whole series: within books it’s a real world, and they [books] are simply an interface, what we see of them. We see them as fixed and immovable, but in fact, beneath the page, they’re all running around like idiots trying to keep books on the straight and narrow. Of course all the characters mix and merge — it’s all very chaotic in the BookWorld.

This book might be easier to get on the whole Thursday Next thing because it features fictional characters: what it’s like to be a fictional person living in the BookWorld, what it is to be a foot soldier in the narrative army, if you like.

It’s really about the difficulties you might have working in this world that is entirely unreal. You do not need to eat. You do not need to breathe. But you breathe because it [the text of your book] says so that you should. So when you exhale, right, you do it to convey a meaning rather than because you need respiration. There’s nothing real to the world. The world is completely emptied, completely nebulous, and we do explain a little bit about that in this book. Also, we have a fictional person going out into the real world, instead of in the other books, which are more like a real person going out into the fictional world, so we have an interesting reversal of that.

[pullquote]People think that if you’re an author then you’ve come from a reading background. I come from story.[/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

How did you wrap your mind around that, because it is a reversal from most fiction writing in that you’re still imagining yourself within this character, but it’s a character stepping into an ostensibly real world.

JASPER FFORDE

It’s a bizarre thing. I must say, when I start to explain the plot and the tiers of metaworlds in which these characters exist, people who don’t know the series start to feel very, very confused and they think they just can’t possibly understand it. Once you start reading the books, aspects of it become not complexities at all but actually fairly run of the mill. I choose as my canvas this world of reading and writing fiction, and what’s real, what isn’t, the ways in which we perceive the real world and our own world and what we want from books, what we like to see from books and the characters in the book are trying to give us, the readers — what they think we want.

THE VARSITY

Where did the idea for the series come from? Have you always been a reader?

JASPER FFORDE

I’ve always been interested in story. A lot of people think that if you’re an author then you’ve come from a reading background. I come from story: It’s film, it’s theatre, it’s jokes, it’s magazines, TV, radio, books — it’s everywhere. My books, because they’re kind of eclectic in the way I write them, very much reflect my taste in stories, which is pretty much from anywhere. So, yes, I did read a lot and saw a lot of movies, too, and listened to a lot of radio, and always enjoyed listening to jokes and that sort of tradition, the urban legend tradition, all these sorts of things, and always liked making stories up. I really come from story.

THE VARSITY

So where did the idea come from?

JASPER FFORDE

Of what, the BookWorld?

THE VARSITY

Yeah.

JASPER FFORDE

Well, the original book was called The Eyre Affair, and this had Jane Eyre kidnapped out of Jane Eyre and someone somehow had to get her back. Now, in that book there wasn’t a “BookWorld” as we know it in the series now, but I was asked to do a sequel to this — and it was originally a stand-alone, The Eyre Affair. To expand upon the world that I’d created, I thought up a policing agency inside Fiction run by characters that we know, like Miss Havisham [of Great Expectations] works for Jurisfiction, the policing agency. Thursday Next, my heroine, finds that in fact she is destined to be an officer in this policing agency. That was really the kicking-off point. Once I had that idea of how that all functioned, then the canvas became immeasurably broad all of a sudden. Writing books about writing and the way we perceive writing, the way we perceive the classics, the way we perceive the ordinary books, everything, makes for a very broad canvas, so I can cover all bases. It’s brilliant.

THE VARSITY

You’re planning on two more books in the series?

JASPER FFORDE

I think it could go on almost forever.

THE VARSITY

Do you have an overarching idea of where the story is going, or are you as in the dark as you start to write a book as your readers are reading it?

JASPER FFORDE

I have no plan at all. I have themes, I have dares, and I have questions that I want to ask myself, and that’s generally how I write. I go “What kind of theme here? What’s the narrative dare that I can give myself?” I often write in that way: I try to think of some impossible notion and then think “Right, how can I make that sort of notion work?” Slinging myself into a dark narrative hole and then clambering out — it’s amazing what you can discover along the way. You want to be a genius when it comes to trying to explain away ridiculous plots — that was essentially The Eyre Affair: Jane Eyre is kidnapped out of Jane Eyre. Okay, let’s put that within the framework of a novel that supports that bizarre idea. Once I created that bizarre world, and now a world within that world, and also of course multiple worlds within the world within the world I’ve created … it makes it a very expansive universe in which to play with almost anything I can think of.

[pullquote]I have themes, dares, questions I want to ask. That’s how I write. Slinging myself into a dark narrative hole and then clambering out — it’s amazing what you can discover along the way.[/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

Is that why you leave your 13th chapter unwritten in each book? Is that to leave some wiggle room?

JASPER FFORDE

It is, yeah. That relates to the No-plan Plan. Cause what I have is, I know I have no plan, I cannot write to a plan, I’ve tried it a couple of times, doesn’t work. If I just start off by writing a plan, I get bored after two weeks, I think “I’m wasting time.” I tend to start with new ideas and then just write and see what happens. It takes a lot longer, or it means I have to work a lot harder, because a lot of stuff just gets slung out. I do like — obviously, it’s a series — I do like them [the books] to have connectivity. So the No-plan Plan is to actually leave myself enough jumping-off points, what I call “on-ramps.” I just do a little open-ended something, a little question, a little jiggly thing, and I keep it open, and then I will close it, maybe one book, two book, three book, four books later — or use it in the narrative to explain another idea that I have. And it’s that kind of ingenious narrative gymnastics that gives the book, I feel, a real complex thread to it. It all plats quite nicely together.

A classic example was in The Eyre Affair: Thursday sees herself coming out of a motorway services, and she’s obviously in some trouble, so she leaves a gun for herself, and then nothing happens for two books. Then in the fourth book, we explain the other side of what happened, and why she had to leave the gun for herself and how she gets out of the whole deal. I had no idea how that was going to work out when I first wrote the section, but I wanted the connectivity. So that is my No-plan Plan. It’s knowing one’s own shortcomings and then making it work for you. But leaving really good open-ended question marks that can be used, really powerful ones — not ones like “The phone rang and then she said, ‘Yes,’ and then put the phone down.” That’s rubbish. No.

[pullquote]That is my No-plan Plan. It’s knowing one’s own shortcomings and making it work for you.[/pullquote]

I have another one where her uncle Mycroft had the recipe for unscrambled eggs in his pocket, and he left that on the wreck of the Hesperus in the poem [Longfellow’s “The Wreck of the Hesperus”]. Now, years later, this became a really good link, because they had to get the recipe for unscrambled eggs — that’s what they had to find, or rather, that’s what they didn’t want to find: they wanted to stop someone from getting to it. That became the book of Book Five. So it was a really specific thing, because the recipe for unscrambled eggs is a really open-ended thing, and it’s clearly about time travel perhaps, third rule of thermodymanics stuff, and I could use that at a later date. So you just have to leave them quite specific, but open-ended enough to be able to play with them later.

THE VARSITY

You set a challenge for yourself of writing a book a year for 10 years. Has that been successful?

JASPER FFORDE

Up until now, it has been. In the U.K. I missed a year because I took two years to write Shades of Grey, but then this year, what are we, 2011? Last year, 2010, I brought out two books, 2011 I brought out one. So I missed a year and then gained a year. So in 10 years in the U.K. I’ve done 10 books.

THE VARSITY

That’s an amazing output.

JASPER FFORDE

I regard that as fairly normal.

THE VARSITY

Really?

JASPER FFORDE

Well I’ve been doing it for so long.

THE VARSITY

I suppose so, but it seems you never stop working.

JASPER FFORDE

No.

THE VARSITY

How much of your working life is the non-writing side?

JASPER FFORDE

Most of my life is spent writing, to be honest. And that’s what a book a year takes you. I think it’s probably better that way. Shades of Grey took two years to write in a very long, drawn-out affair, and I probably could have written the same book in half the time, but because I had the time available, I let it just string out. There’s something about when you’re writing and you get into a writing frenzy, and all of a sudden everything’s in your head, and everything’s all kicking off, and you’re having tonnes of ideas because you’re totally immersed in it. But if you write for 10 minutes, and then walk around for 10 minutes, and then come back and do five minutes, and then have half and hour off, and then do another two minutes, you’ll never get up to that critical mass. But when you’ve got a deadline that is looming up, and you know that you’ve got to write this book and you’ve only got 70 days, and you know it’s going to take 70 days to write, then it does focus the mind wonderfully. If you can do 10 hours a day, real focused writing 10 hours a day, that is the same of doing a week and a half, two weeks of the dribsy-drabsy, I-don’t-have-a-deadline, I-can-muck-around sort of time. So in fact the deadline of one book a year helps a great deal.

THE VARSITY

Before 2001 I understand that you spent a lot of time trying to figure out writing.

JASPER FFORDE

Yeah! I started writing in ’88, and I wasn’t published until 2001, so that’s, what, 13 years? And in that time I wrote I think six and a half novels in my spare time, and a lot of rejections for that, but probably quite rightly so. I think it was me learning my craft, learning to write in my slightly strange way that I do.

THE VARSITY

Are you conscious of having a writing style?

JASPER FFORDE

No, not really. That’s pretty much how I write.

THE VARSITY

That’s that kind of story you lean towards, these alternate worlds?

JASPER FFORDE

That is my kind of difficult style. Description is slightly harder than dialogue. Dialogue I find very easy, and situation, and stuff like that. When I do description, I have to work twice as hard to make it work, and that’s when I feel the style does perhaps come into more of a written style.

THE VARSITY

What did you learn from those 13 years?

JASPER FFORDE

Well, everything really. Not just about how to get stuff on the page, and how to make it engaging, but really the subtle parts of writing. It is an infinitely subtle dark art, writing, because you can change a scene very easily just by a few words, or just taking out a line. It’s really just looking at the page and knowing whether that works right for the tone of the bit that you’re doing. Making dialogue naturalistic, getting people in and out, writing in chapters itself is quite hard because a chapter is essentially a scene, and you don’t change scene, you don’t say, “Right, they got in a taxi and they went somewhere else.” You generally want to finish the chapter there and then start another one. A chapter should be I reckon about 3,000 words. So getting people on stage, getting people off stage, making sure that dialogue actually goes in a smooth direction. You’ve got that one or two things that you want to get out in the dialogue, but you don’t want to be obvious, you want to show rather than tell, so you have to have dialogue go in a logical way in which people talk to get the two bits of information out. How to make characters work, how to add just the smallest amount of description that can convey a feeling and mood. Those 13 years were spent staring at the screen and thinking, “Now, why did this work? How could this be slightly better? Does it need to be this long? Can I shorten it? This chapter is 5,000 words. I think that’s too long. How can I take out 2,000 words?” Usually the answer is “very easily.” There’s no book on the planet that’s 100,000 words that couldn’t be told just as well in 70,000, or maybe even 50,000.

THE VARSITY

Just now you were using a lot of terms from stage direction. You’ve said that writing a novel is like making a film, except that as a novelist you do all the jobs yourself.

JASPER FFORDE

Oh, definitely.

THE VARSITY

What do you mean by that?

JASPER FFORDE

Well, in a film there are lots of different people, you know, 500 people, and they all do their very specific skills. When you’re writing a book, you’re essentially doing everything yourself. Everything. You’re being all the actors, you’re writing all the dialogue, you’re doing all the directing, the building of sets, editing — absolutely everything. But you could just as easily say that a film is exactly like writing a book, but you have different people doing the jobs. So I don’t see that there’s that much difference, or that the similarities in making films is anything more than how we make stories. I don’t really see that movies and books are so very very different — it’s just a different way of telling a story.

THE VARSITY

In the book you imagine what it’s like to be living in one of these books. The characters’ identities are tied to their literary character, but they also have this actor aspect. Even the books are very much like film sets. Were you purposely drawing on your experience in film?

JASPER FFORDE

I think it’s grammar that people understand about storytelling, and it seemed a logical kind of storytelling, because you can also draw on the fact that many of us are actually just playing the person that we want to project all the time. The whole thing of social discourse is essentially a whole set of rules that you wear on the outside. And the things that you think on the inside are either suppressed or you don’t really want to do or say, because that’s not how one gets along. It’s a very complex thing, social animals that we are. So in that respect I think film sets, again, are very much like life and how we do things.

[pullquote]It’s about a woman trying to find herself. It’s wrapped up in a lot of silly fun, but there is also this search for knowing who you are and what you’re meant to be doing. [/pullquote]

It also seems strange that you can listen to the news of some terrible disaster where thousands of people have died, but shed no tears, yet can go to the cinema or read a book, where you know that the people are fictional, and yet have an emotional response. So there’s something very complex there, which is all about social discourse and the sharing of emotions. It’s a strange thing that fiction and stories have this power over us. We become involved with the characters within the fiction, and they become, they are, us. We know them very well, and we care for them. All of a sudden, it becomes very real.

THE VARSITY

Well, and the problem that the written Thursday has in the book is — there’s the whole crime aspect to be figured out — but her whole issue is, Who is she really? She needs to discover is she the written Thursday or is she the real Thursday? It’s a constant question. But it’s a question that a lot of people have.

JASPER FFORDE

Yeah! Who are they? Someone asked me what the book was about and I said “It’s about a woman trying to find herself. But not her self, her other self. And is she really herself?” It’s wrapped up in a lot of silly fun, but there is also this search for knowing who you are and what you’re meant to be doing. Are you meant to be a good person, should you play the same game — all these sorts of issues that the written Thursday has are, I feel, the sorts of issues that people generally have in real life, and it’s that I think that makes an empathetic character, because we’re meant to think with her.

She’s quite vulnerable. She’s had loss. She finds that the man that she loves is essentially dead. She’s been written with all this love in her heart for someone who died. She’s left with this clumsy plot device that she has to deal with, and then she meets the real husband that she doesn’t have and the children she doesn’t have. How do you deal with that? Do you come clean? Do you pretend that you’re the real person? Can you take over from the real person?

THE VARSITY

There are a lot of moral issues there.

JASPER FFORDE

Well, there is! I always like putting in ethical issues. There was a whole sequence in First Among Sequels where Thursday finds herself on the SS Moral Dilemma, and she constantly gets these ethical dilemmas thrown at her. Thursday has to deflect these dilemmas, and when she can’t, she then has to find the true way to deal with problems of that sort. It was written at the time when the Gulf War [the Iraq War] was going on, and there were huge ethical dilemmas about what do you do in those sorts of situations, and it was trying to just cut into that and look at the issues.

THE VARSITY

We haven’t talked very much so far about the Outland. Admittedly it’s not a very big part of this book. But something that I find interesting about your series as a whole — because you have Shades of Grey, and while there are humorous aspects to that book, I think a lot of people would recognize that it’s a dark, dystopian universe. But I think there’s also a dark aspect to the Outland in that the Thursday Next books are still comedy, but we have the Goliath Corporation, there are various conspiracies going on, an underlying issue of the series is the abuse of power. Do you intend it to be read as a satire?

JASPER FFORDE

It is, yeah. I describe Thursday’s world as being just like ours only more so. I just take particular aspects of our world and then hugely exaggerate them for comedic purposes, for three reasons. It makes the world very recognizable, so people can see that it is in fact our world. It also makes it quite amusing. And it’s also another good way of asking pertinent questions, or starting a dialogue, or just pointing out the obvious. That’s the thing about satire: we do very strange things as humans often without thinking. When you write satire, you can actually highlight the stranger, more bizarre aspects of human behaviour, and say, “Why are we doing this? It just seems so strange.” I find it amusing and fun.

THE VARSITY

One of the lessons I take from your books is that the circumstances that surround a person can vary greatly, but human nature doesn’t really change all that much. Is that your own belief?

[pullquote]The series takes place in a parallel universe in which everyone loves literature — but it’s no less violent. It’s a case of huge intelligence but very little wisdom. [/pullquote]

JASPER FFORDE

Oh yeah. The series very much takes place in a parallel universe in which everyone loves literature that much more — but it’s no less violent. So everyone is extraordinarily well read, and yet they’re still doing the same dark things all the time. So I think it’s really a case of huge intelligence but very little wisdom. Irrespective of how smart we can be, we still have no wisdom. And I think one thing that I do put in Thursday’s world is this notion that it’s a bizarre world, but it is recognizable.

THE VARSITY

Is it any more bizarre than our own?

JASPER FFORDE

Well, I used to think it was, but in the latest book I have the written Thursday coming into the real world, and she finds it very very strange to be there. All the things that we take for granted, like breathing and walking and moving through crowds — which is very complex, actually: two crowds of people will actually go through one another quite happily walking in two opposite directions. We’re all working by the same rules. And we know that the other person is also working by the same rules. So that thing you get when you meet someone [in a Droitwich†] is actually quite rare and quite amusing — it just doesn’t happen very much. It’s that kind of thing that in the real world is very strange and the fact that we see it as normal is only because we’re used to it and of course we’ve grown up with it. But any sort of alien appearing on our planet and looking around would say, “There is no logic to this!” You know, Mr. Spock would … “Illogical, Captain.” And he’s right! We’re very strange, we do things for all kinds of weird reasons, mostly it seems through strange passions, decisions made seemingly by emotion and nothing else. Logic doesn’t take a forward seat in a lot of stuff that we do. And of course when you’ve got 6 billion people all making strange decisions based on emotions rather than anything else, it makes for a very odd world.

———

†Droitwich v. & n. “A street dance. The two partners approach from opposite directions and try politely to get out of each other’s way. They step to the left, step to the right, apologise, step to the left again, apologise again, bump into each other and repeat as often as unnecessary.” — Douglas Adams, The Meaning of Liff

———

THE VARSITY

In other interviews that you’ve done, you’ve seemed to bristle at attempts to put your work within a given genre, or to fit it within that x-meets-y sort of book marketing, which is why I found it strange that with this book everything in the BookWorld is now very much structured around genre, relationships between books, worrying about the book that moves in down the street. Has your thinking changed on this?

JASPER FFORDE

Well, the new book’s geographic BookWorld does in fact make things a lot more ordered. I think I should have done it right at the very beginning. It would make it much easier to write sequels given this form of BookWorld, because then there’s more satire about differing genres having their own separate agendas, which I think is very true. So I’m using the notion of genre, which I regard as what I call the measles of BookWorld. In the BookWorld I have warring genres. Racy Novel is being denied basic characterization, and they’re saying “It’s stopping us from developing as a genre. How dare you sanction us.” And Feminism doesn’t believe that Racy Novel should exist. So there’s all sorts of little parallels you can have with nations of the world, and the frictions you can develop through having all these different genres I think makes for a more colourful book, and certainly a more easily understandable book.

THE VARSITY

The BookWorld seems to work on this premise that if the fixity of a text isn’t maintained through constant performance it could fall by the wayside. It brings up a lot of questions that you’ve mined. I’m wondering specifically about this whole notion of feedback loop that you talk about: readers give something to the book by reading into it. They read in description or associations — things that were never in the text but make the book richer through the process of reading. What has your own experience been with readers of your books and what they read into your stories?

JASPER FFORDE

Because a book is completely abstract — I mean, literally, it is ink on a page, right? — to comprehend the novel is something that happens up here, in the head, and it only comes alive in the reader’s mind. If you wrote a book in a language that no one could understand, and then you lose the language, then essentially the fiction has gone completely and is irrecoverable. Yet it was once there, which is kind of weird. I’ve always maintained this idea that readers are doing most of the work. That’s the principle I’ve come to from the BookWorld. I’m waiving mnemonic flags: I say, “Well, this is how I had this feeling. Let’s see if you do as well.” It’s almost telepathic, if you like. I do like the idea that readers are the people who make books come alive — it’s their hard work.

THE VARSITY

How big a step is it from that to fan fiction? In your book, Fan Fiction is off on another island, off Fiction proper. It shares the island with Vanity publishing, and both are somewhat disparaged by the inhabitants of Fiction. Is there much Thursday Next fanfic?

JASPER FFORDE

I’ve never read any, but I’ve heard there is. I do get emails from people who try and explain what fan fiction is all about, and I was originally quite disparaging about fan fiction. I thought why waste time writing my characters when you could write your own characters, and then you’d have your own book? That’s how I see it, but it isn’t how fan fiction people see it. I’ve modified my opinion to say, well, fan fiction is actually a celebration of fiction. It’s not about simply copying, or anything like that. So I did modify my opinion, and wrote that into the book as the modification. But I suppose I don’t mind people doing it. It’s never going to be published, for obvious reasons, and if people want to write it, all writing is good. Any writing is good, essentially, I think, as long as it’s not going to harm anyone or make people do illegal or unethical acts. All writing is good as far as I’m concerned.

THE VARSITY

Where do your own characters come from? You have the benefit of being able to use literary characters as a kind of shorthand. Maybe you don’t have to go into a whole description of what Mr. Rochester looks like, but where do you find inspiration for the alternate Mr. Rochester, who he is outside the plot of Jane Eyre?

JASPER FFORDE

Well, he’s kind of like who he is, but not quite. And it’s like the character that he plays — like going back to what we were saying before of the person that you project is not necessarily quite the person that you actually are. People don’t really change, but you get to know them better, and then you realize what’s going on. Most people have an agenda and that always comes through: it affects everything they say and do. When you understand a character’s agenda, then you can actually understand a character a lot better. So when I’m writing a character, I say to myself, “Right, what is the character’s agenda? What does this person want more than anything else?” Like, do they just want to do right, do they just want to have a good life, or if it’s more complicated, then do they want to be famous? If they want to be famous, are they going to be evil and that’s the way they’re going to become famous? Once you start writing their little secret agenda, the characters make a bit more sense. And the weirder the agenda, actually, the more interesting the character. Often you meet people and you think they’re being very strange. You think about it for a while and then you try to figure out what their agenda is, and then all of a sudden the things they say and do actually make sense. Everyone has an agenda.

[pullquote]They’re books about stories and stories about books, and that’s for people who read books. [/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

I’ve read that you’re hesitant to even talk to anyone about film adaptations for the series unless it’s you doing the films yourself.

JASPER FFORDE

Yeah, I used to think that, but that’s not going to happen.

THE VARSITY

Yeah? No longer?

JASPER FFORDE

No, the film adaptation is, generally speaking … I don’t need to make them. They don’t need to be made as movies, I don’t see it as a logical progression. It seems to be accepted wisdom that a book becomes a film, and that’s what you do with books. I don’t see that at all. It could actually be a retrograde step. In many instances, it is. And because I don’t need to, I don’t need to let them go, I don’t have to let them go, I will only entertain filmmakers who I feel are going to do a service to the book. And because once it’s sold I have absolutely no control at all — you know, I can’t do anything once it’s sold — I have to make sure I sell it to the correct people. So what we do is, we essentially say, right, if the producer wants to talk to me about the project, then we’ll only talk to players, which means we have to have heard of one of the films they’ve already made — because I could spend my entire life talking to first-timers and wannabes — and then we may have a meeting. And in 10 years we’ve had two meetings. I could sell them to auctions [snaps fingers] just like that. But then they could sell on the auction to someone else. Before you know it, there’s some screaming disaster made and I hate it. Also, essentially they’re books about stories and stories about books, and that’s for people who read books. I don’t think film people really understand books, because film people generally use film as their primary method of entertainment.

And I always think that when film directors make a film, they should actually put their name in front of it. You know — “Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings” — because then you know it’s his take on it. Because everybody has a different take on the book, and that’s why people always complain about films not being how they imagined it. But how can it be? Because everybody has a different way of looking at the book.