Iam sitting in an auditorium.

My exam is in front of me. I have studied. I have brought seven pens because of the time in first-year my pen leaked halfway through the final essay question. I arrange them on the top left corner of my desk. They are aligned at the bottom from tallest to shortest, left to right.

The exam begins. For three hours I must be focused. Coherent. I feel good.

And for the first half hour I am good. But then I reach The Question. It isn’t that I don’t know the answer. I just don’t expect it. Maybe it’s worded strangely. Maybe the answer could be ambiguous. Whatever it is, The Question has triggered The Panic.

The Panic reminds me that if I get The Question wrong, I will have to get the rest right. If I don’t get enough of the rest right, this will have a negative effect on The Final Grade. If The Final Grade is low, that will pull down The GPA and once that happens there will be a negative effect on The Future. Once The Future is affected, I will probably be left by my girlfriend, abandoned by my family, and will one day live under the underpass.

My focus is gone. I am no longer present, but shuffling through possible futures. None of them are good. My anxiety rises and my thoughts become more fragmented. My pulse quickens. My handwriting, my spelling, and my writing style all fall apart. I have failed exams this way.

I find myself counting. I find five things that I can see (the red door, the bored TA at the front of the room, the brand name of my pen, my own name on the exam booklet, the tile pattern on the ground) and soundlessly repeat them to myself. Then I begin listening. I count five things that I can hear: the clock ticking, my breathing, the rustling of pages being turned, the scratching of pens on paper, the slight cough of the girl beside me. Finally I pay attention to what I can feel: the coolness of the pen in my hand, the smoothness of the exam booklet, the rigid shape of my chair, the hardness of the floor beneath my feet, the itchiness of the cheap cotton t-shirt I’m wearing.

Then I count them again, but this time one less. Four things I can see. Four things I can hear. Four things I can feel.

Then three, three, three.

Two, two, two.

One. One. One.

Finally, I am present again. I complete the exam. I will probably do fine, and no one will ever know about the 10 to 15 minutes I spent severed from the present. The only indication will be my t-shirt soaked through the armpits with sweat, but I will eliminate that evidence the moment I get out of the exam. Just like I always do. I will make my way to the first bathroom I can find, lock the door, remove my shirt, and hold it under the hand dryer. That is my ritual. Me, standing at a hand dryer, arms outstretched, motionlessly holding my shirt in shame.

And I am ashamed. I am ashamed in a way that has kept me from seeking treatment for 12 years. I am ashamed of having to admit that my needs might be different from what is supposed to be ‘normal.’ It is only in the last two years that I have started seeing a counsellor. It is only now that I have started practising breathing techniques. It is only now that I have asked my old family doctor, who last saw me when I was 16, for a referral to a psychologist who could assess me.

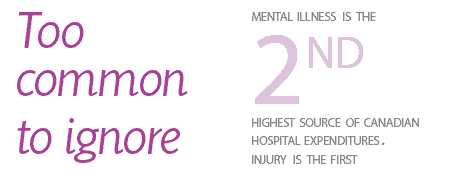

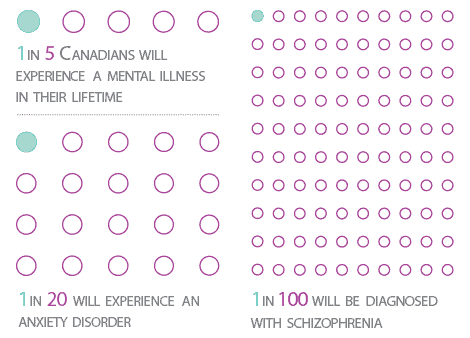

But the reality is that I’m not the only one who copes with anxiety. According to a Canadian Mental Health Association, five per cent of Canadians are affected by anxiety disorders, a significant part of the 20 per cent of Canadians who will experience mental health issues in their lifetime.

If these statistics are accurate then an average 20-student tutorial is likely to contain four students with mental health issues. One of those four may have an anxiety disorder.

The University of Toronto does not ignore these issues. Our enormous student population guarantees that there is a virtual army of anxious, depressed, manic, or otherwise-affected students with needs that must be met. Accessibility Services, Counselling and Psychological Services, and the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work are just some of the services provided on campus to support students.

Janine Robb, Executive Director of Health and Wellness at U of T, handles the mental health component of these services.

“Mental health is a continuum,” she says. “It is not simply an absence of symptoms. It’s an ability to function, to enjoy life, to make good choices, to be participating. Because you can have a depression, and be able to do all that. You can have bipolar disorder and do all that.”

Robb couched her views with those of the University of Toronto. Overall, U of T services have a more general commitment to equity — a commitment to the rights of all students and a commitment to providing them equal access to education.

But despite the inarguable stated commitment to mental health on campus, stigma still interferes daily with students’ lives in subtle and sometimes surprising ways.

Amy, a third-year student diagnosed with Asperger’s disorder (the names of students quoted in this article have been changed to protect their anonymity), noted that University of Toronto staff often assume — if most often unconsciously — that diagnoses reflect a negative component of students’ personality.

When she went to speak to her registrar about an accessibility need, Amy was surprised that her registrar responded to the disclosure of her particular diagnosis with something along the lines of, “Wow, you don’t present as that at all!”

Amy was shocked because accessibility needs are often invisible; she had expected that her registrar would be used to students having a wide variety of needs, whether or not those needs are immediately apparent.

“Hearing something along the lines of ‘Wow you really don’t present like that,’ makes it seem as if she is: one, making an attempt at a compliment by telling me I present ‘normally,’ which assumes that anyone with a disability must aspire to be normal, i.e. someone without a disability, and two, de-validating the needs I have — even if it’s an unintentional de-validation, especially if it’s an unintentional de-validation — as someone who identifies as having Asperger’s disorder,” explains Amy. The invisibility of her diagnosis makes it no less real.

“Even if the outer representation of self doesn’t reflect a diagnosis, [it] doesn’t mean you’re not interacting with it on an interior level every day,” she continues. Amy has found that while her registrar has always been supportive, extremely helpful, and mostly sensitive overall, this initial reaction indicates how old patterns of thought can result in slips that challenge the level of equality to which the University of Toronto aspires.

Lindsey, an instructor I had last semester, prioritized this equality. She prefaced her class’ late policy with an account of how she had coped with death and suicide during her own undergraduate experience, and emphasized how important access to the appropriate services was to her. She provided resources for where and how students could find the services they might need. Finally, she explicitly stated that she did not need to hear the full backstories of individuals’ mental health issues in order to acknowledge their needs. Instead she promised to do everything in her power to meet the needs of any student who provided her with documentation of their needs. She realized that students with mental health issues do not need to make excuses for why they don’t fit the idea of normal. What they need is to be recognized and accommodated.

But even with the kind of recognition available at a university- and Accessibility Services-level, students still face the possibility that stigma will cause their diagnosis to be misunderstood by friends and family. For students returning home post-diagnosis, there is the chance that the place they return to will be compromised. For these students, a diagnosis does not mean they are returning with a new tool that identifies their needs, but that they are returning as a manifestation of their diagnosis. They become seen as the crazy person, someone beyond help.

Terrence, a student leader and musician, recently received a borderline personality disorder diagnosis. For Terrence, the only issue he had with the services provided by U of T was the initial difficulty of finding help. Since he obtained his diagnosis he has found both faculty and staff to be incredibly supportive. Instead, it is at home that he faces stigma. It is at home where Terrence’s diagnosis is treated not as part of his multi-faceted identity, but instead as his identifier.

“The initial reaction from my family was not a good one. They were not prepared and are still unsure about how to manage a 21 year-old living under their roof with a mental illness,” he admits. Terrence’s family made him feel like a crazy, irrational individual who no longer met the criteria for what they considered ‘normal.’ The stigma within his home distanced Terrence from the support system he was accustomed to.

“My family’s reaction made it harder to handle my academics, mental illness, and general life,” he says. “I felt uncomfortable being home and did everything I could to stay away because I felt more comfortable being somewhere my illness was either not in question or better understood.”

When we discussed how his family reacted to his diagnosis, Terrence acknowledged that you can only react to what you know and understand. “My family had no education on the subject. How do you manage a person with a mental illness?”

Stigma challenges us in our own minds, our classrooms, and our support networks. It is what is left behind from the old ways of thinking about mental health. Dr. Tanya Lewis, Director of U of T’s Accessibility Services, noted that we are still facing an attitude adjustment towards mental health, disability, and accessibility.

“For a long time we’ve been in a medical model where it says there is something wrong with you — a mental illness — and you need to do the rehabilitation to fix yourself to fit into the world with everybody else,” she explained.

But this system of thought has largely been replaced. “The [newer] term Accessibility Services comes out of disability studies that says what creates the disability is the world in which we live … the world creates what we call disability barriers.”

Lewis references someone with a physical disability as an analogy: they might not have trouble accessing what they need until they are confronted with a world in which stairs have been invented and adopted as the norm. Mental health is the same.

Robb also acknowledged that mental health assumptions need to change, and offered her own insight on how stigma can be tackled.

“It’s [about] continuing to have an open discussion that’s not judgement-laden,” she says. “It’s reminding people that taking care of your mental health is no different than physical health.”

We stand at a threshold for mental health discourse. No matter how much training and educating is done, it seems like the old way of thinking about mental health still inevitably emerges. If we — whether it is the student body, the university, or the individuals that work at the university — hope to have a truly equal system, then we must make a new one. One that allows those affected by mental health to truly participate in society like the fully capable individuals they are. One that looks at the stigma of the old guard and challenges, de-constructs, and discards the disability barriers it creates.

One in which I can align my pens and use them too.