Lace-trimmed bras and underwear don’t exactly bring to mind hard-hitting tackle football, but that’s precisely the uniform in which the Toronto Triumph lingerie football team takes to the field.

The Triumph have made headlines since their arrival in Toronto this past summer as an expansion team from the US Lingerie Football League. The team was initially met with harsh criticism from feminists and concerned citizens alike who, understandably, argued that the city did not need to support such a scantily dressed team.

The Triumph have also recently graced the pages of Toronto sports sections for reasons other than the team’s dresscode. In October, 22 of the original 26 players on the team resigned over disputes about unqualified coaching staff and unsafe equipment that included hockey helmets and one-size-fits-all shoulder pads designed for male youths.

The players quit after only the first game of the regular season, which the team lost 48–14 to the Tampa Breeze. By the next match, 12 of the 16 players preparing for the game at Ricoh Coliseum had only just completed their first week of team training. The most recognizable member of the Triumph, Krista Ford, daughter of city councillor Doug Ford and niece of mayor Rob Ford, was one of the first players to quit.

If these women were playing flag football, proper padding would not be as serious a concern. There’s a reason that football teams only play once a week while other sports can play on several consecutive days, and it has nothing to do with th

e determination or resilience of the players.

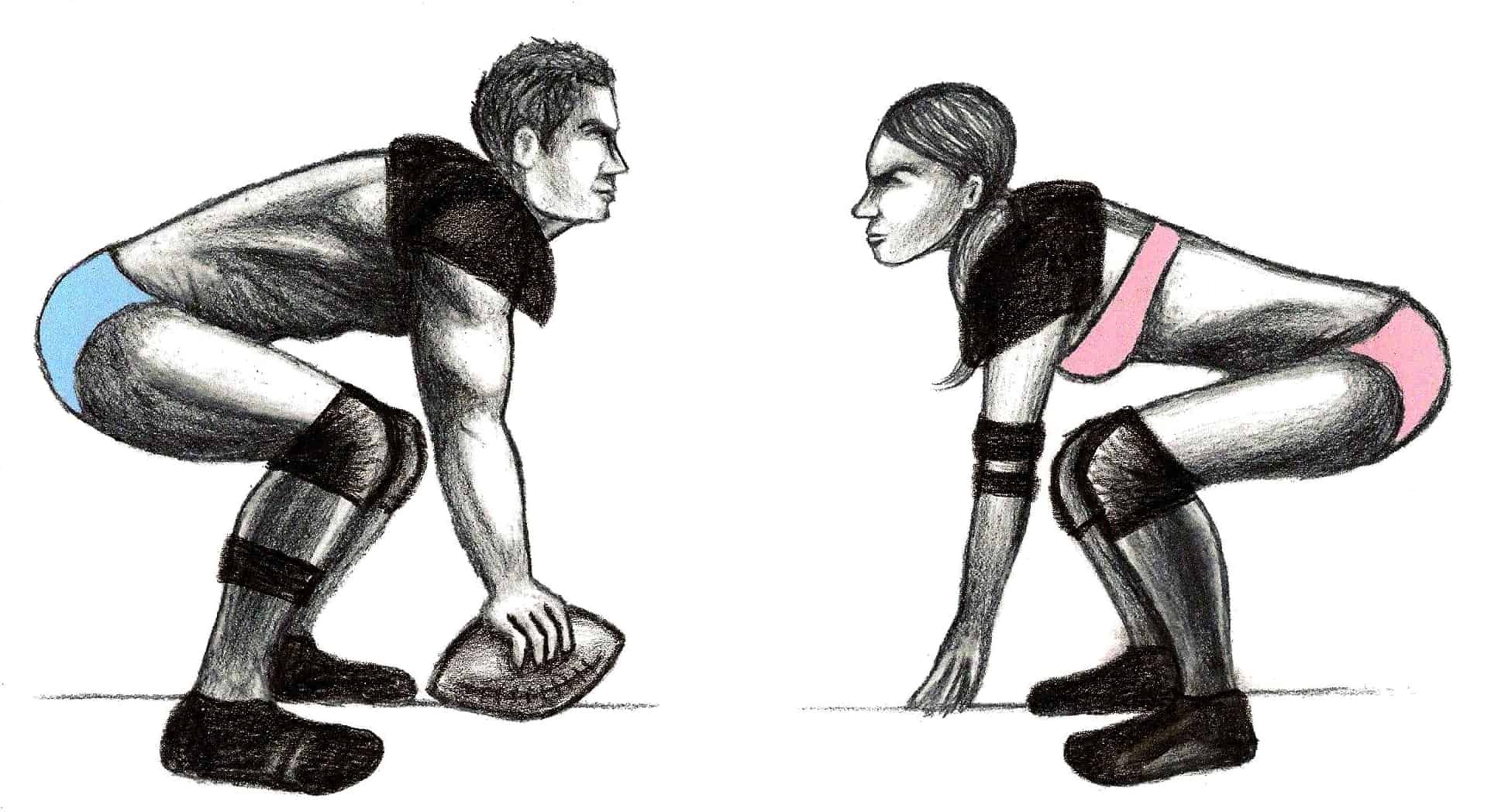

Football is a full-contact game in which players line up nose-to-nose and face off in a battle of “who can hit the guy on the other side of the ball the hardest?” Without proper padding and educated coaching staff, it is not a matter of if injuries will occur, but when.

“[As] a [woman] who plays a full contact sport, I am fully aware of [the] need to have a proper coach and equipment. If you don’t, accidents and injuries will occur,” says Amanda Capone, intramural representative for Woodsworth College and a Varsity Blues rugby player. “I play a full contact sport, and if I were to play in nothing, I think I would feel a little more vulnerable in terms of getting hit.”

In late October, Dalla Giustina, one of the disgruntled players, told the Toronto Star, “When the head coach and the other offensive coordinator ran a practice, it literally felt like we were having a golf instructor teach us how to play professional football.”

“Professional” seems like quite a stretch. As a woman who spends the vast majority of her time consumed by football related activities, I don’t believe that women cannot, or should not, be interested in sports, or that “real” football is reserved for men. But equally I cannot reasonably argue that any group of players — not necessarily women — wearing just their undergarments and some strategically placed padding can possibly constitute a “professional” team.

“There are also full contact football leagues for women who are fully clothed, but they get no recognition,” Capone points out. “I feel like even other leagues — like team-Canada leagues for other sports — don’t get as much attention as this team does. And … as much as people don’t want to say it, it’s because [the players are] almost naked.”

The Triumph’s team website (lflus.com/torontotriumph) shows about as much cleavage as any a magazine hidden in the top rack of a seedy convenience store. “I know some of these girls, and they are competitive athletes,” says Capone. “But it still reverts back to that of ‘why do you think you need to do that?’”

There’s no doubt that some of these women are real athletes, who have been training their whole lives, and wake up with a yearning to hit the field to perfect defensive formations.

“They actually are pretty tough,” admits Michael Prempeh, one the Varsity Blues football team’s leading receivers this season. “You see girls running into each other at full speed, and I was surprised.

“Some of the girls looked like they could run me over if I got in their way. If it wasn’t for the lingerie, it wouldn’t be that much of a [big] deal.”

So would Prempeh be willing to play in boxers in a male-equivalent of the Lingerie Football League? “I would feel a little bit weird. That would be way too weird for me; I don’t think I’d be able to do it.”

Though the athletic requirements are clear, lingerie football does make good-looks a prerequisite for participating. Enough Hollywood movies have enforced the idea that girls aren’t comfortable with sports; are we then to tell them that to play football in a large-market city like Toronto, they must be minimally clad?

“When I first heard about this, I was kind of torn because I did have a friend that was trying out,” admits Capone. “But my own personal thoughts were that it kind of just devalued the athlete and any sort of athleticism that they had.

“They had to basically run around in nothing, to prove to themselves, and to prove to other people, that they’re worthy of competing.”

Members of the Chicago Bliss, another LFL team, had to sign contracts recognizing that they would face fines if caught wearing any additional undergarments beneath their uniform. The Chicago players also had to agree to “accidental nudity” during games and practices. Clearly, sex sells.

Chairman Mitchell Mortaza told the Calgary Herald that the LFL is the fastest-growing professional sports league in the United States, but changes to the league mean that once-paid professional sports franchise now rely on players who are essentially volunteers. Players are offered a limited insurance plan for team injuries and tanning and have to pay a $45 participation fee to take the field.

“They’re athletes: they train, they study football, they’re out on the field putting in work,” says Prempeh. The LFL apparently does not think it needs to pay these athletes for the “privilege” of playing football.

To Capone, the lingerie angle is unnecessary. “You can be an athlete without having to take your clothes off.”