People are reluctant when changes are recommended to the creative neighbourhoods of any city. Proposals are followed by uproar from residents, businesses, and patrons with the usual cries of “We don’t need change,” “Down with capitalism,” and Fuck Starbucks.”

So why change something that Toronto loves and finds sacred? Kensington is well-balanced, juxtaposing its own counter-culture with the Towers o’ Finance further downtown. The neo-vintage shops stand beside immigrant grocery stores perfectly, though in a very postmodern and hipster sort of way. Kensington Market, with its unique mix of community, culture, and city planning, has become a nexus in downtown Toronto, linking residential areas like the Annex with the commercial ones of Chinatown and Queen Street.

We are big fans of this area. We live in and around it, and it’s where we take our visiting friends first — to show them that Toronto is not all CN Tower and big bucks. Kensington’s greatest achievement is that its years of popularity have not stopped it from serving the entire spectrum of economic class. Its bakeries, butcher shops, and supermarkets — that sell far cheaper food than your local chain grocery store — lie beside shops selling your grandma’s now-hip vase back to you for eight dollars.

From an urban designer’s point of view, it is mostly a dream come true: dense, diverse dwellings with short city blocks and a mixture of old and new buildings. The mother of modern context-based urban design, Jane Jacobs, sought her second home here. Kensington’s urban design success is the root of its success as a neighbourhood.

But come nightfall, Kensington shows its dark side. Shops close and the streets are deserted — it’s nothing like during the day. Some find this a necessary evil; creativity seems to spring up most in shadowy places — see ‘80s, ‘90s NYC — but so do crime and danger. Let’s face it, most of us have a weird story about Kensington at night.

As a place so vaunted in the daylight, why shouldn’t it be as successful at night? The principles of urban design can go a long way toward forming the mood of a neighbourhood. Here’s how they could make Kensington safer at night.

Illumination

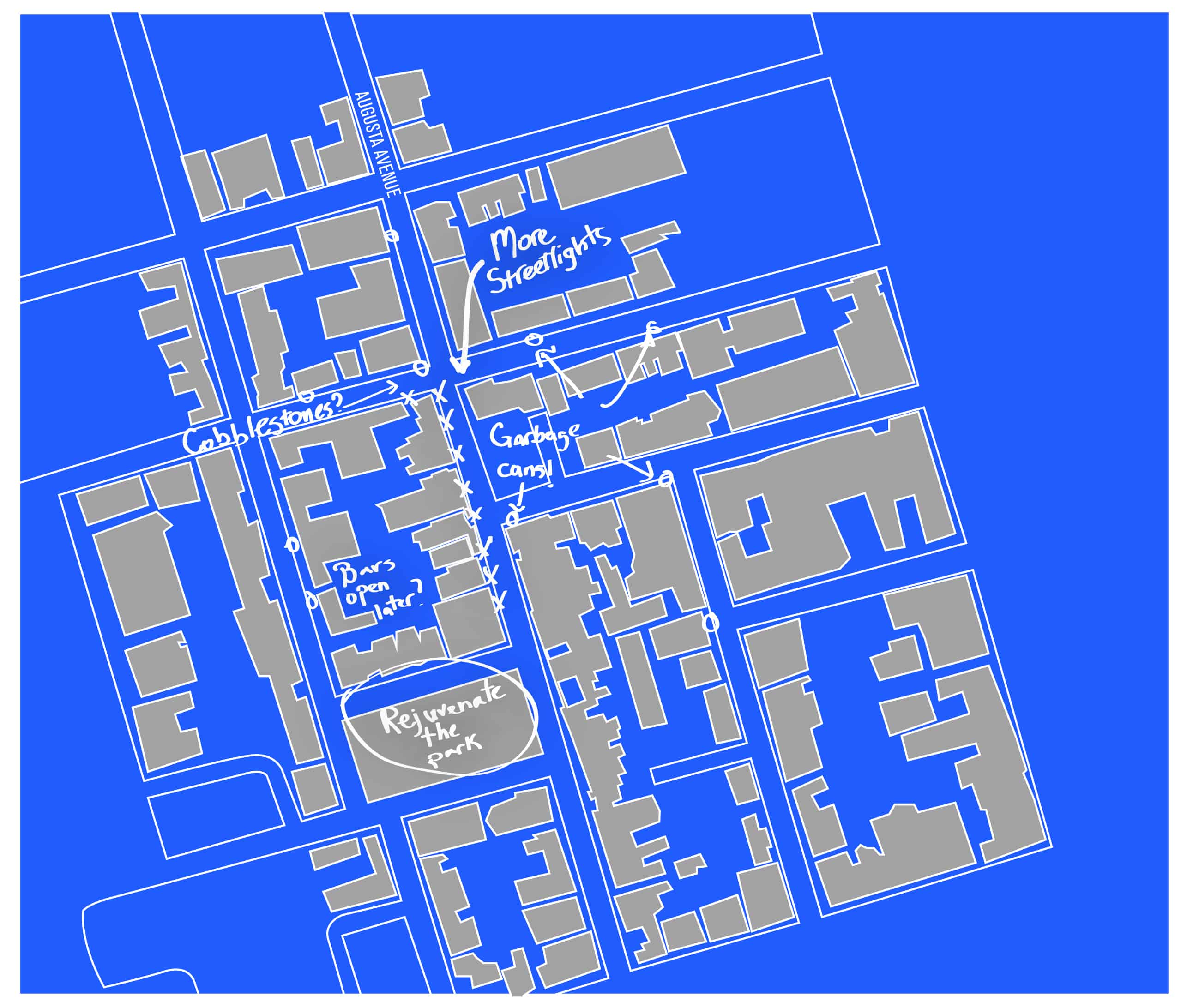

With its creepy, sparse, argon street lights, Kensington is in dire need of better lighting. New lights should be designed to illuminate wide areas and they should be bright enough not to create shadowy ones. Lights could improve Kensington’s mood and accessibility. If you think of successful “night-bourhoods” like Bloor, Queen, and Richmond, however, it’s not just the streetlights that illuminate the street, but the lights and signs of shops, restaurants, and bars as well.

Store hours

Most shops in Kensington — especially below Baldwin in south Kensington — are notorious for only operating during the day. When the grocery stores close down, Kensington dwindles down to a fraction of what it is in the daylight. If more restaurants and bars stayed open, not only would the streets be better lit but more people would be out and about, giving the area a greater sense of security. Jane Jacobs’ idea of “eyes on the street” finds its perfect application here. Kensington is in a prime location, near the university and other bar districts, and its business owners have the creative ability to capitalize on the hungry and thirsty nightlife crowd. For students, it would be great to have a decent bar close by and more food options than Chinese at 3 am. Still, there needs to be a balance so that late-night bars and restaurants don’t disturb Kensington residents.

Pedestrianization

It seems an obvious measure to pedestrianize an area that is dominated by pedestrians and cyclists and that serves as a tourist attraction. The success of Kensington’s monthly pedestrian Sundays cannot be ignored. However, food stores and grocery shops heavily rely on cars both for delivery and customers, who prefer not to carry their grocery-laden bags for too long. In our opinion, Kensington is pedestrian enough. The narrow streets force cars to drive more slowly, and on crowded days, most Toronto drivers know to avoid the busy neighbourhood anyway. Cobblestone streets, though expensive to install, would increase the dominance of pedestrians by acting as speed breakers for cars. They could also make the area seem more walkable and improve safety by making cars audible at night. Conditions for bikers could be maintained through a tarmac strip as a bike lane.

Parks

Parks are an integral part of city design and are a microcosm of the region where they’re located. Bellevue Park reflects south Kensington’s daytime energy and nighttime sparsity. Redesigning the park to include more communal functions would change the area from a neglected fringe to a focal point of Kensington. A well-lit park, featuring community projects such as an artist’s wall or stage would reintegrate it with the area and make it a more desirable place to walk through at night. This would have a synergistic effect with the adjacent businesses open at night, ensuring more users for the park.

Garbage bins

Also more garbage bins. That will be all.

An extended history of Kensington Market

Change in the Market is always met with hesitance and public scrutiny.

For instance, the Kensington Garden Car, — albeit a great initiative outlining our society’s dependence on cars and the importance of the environment — caused much uproar in the community when there was chance of its removal. The fear of change is a proper concern in any bohemian neighbourhood. As history has shown, gentrification and commercialization can strip away the very thing that makes an area unique. The proper course of action is not to reject change in all its forms, but rather to embrace and encourage “proper” alterations.

Change in a city is an ongoing process: no matter how well the area is maintained change will always trickle in. It’s important to remember that Kensington Market became what it is today through years of change and alteration . The Market’s unique atmosphere comes from generations of newcomers to Canada settling and raising their families in the region. The Irish workers in the1880s, followed by the Jewish immigrants in the 1900s (when the area was called the Jewish Market), and then a subsequent mix of Portuguese, Caribbean, Latin American, Asian, African, and Middle Eastern arrivals, have all left their cultural imprint on Kensington Market.

The Market, therefore, has been built upon the economic foundation of entrepreneurship centred on small family-owned businesses concentrated throughout Kensington. But for such areas of business to maintain themselves there needs to be strong support from the community, and this can be generated either from a specific immigrant group or from a dense residential area — the importance is in having these businesses locally integrated.

The problem lies in the significant popularization and commercialization that the area is currently undergoing. When the area becomes a tourist attraction the parts of the Market that are less economically functional are displaced for more profitable businesses (such as retail and restaurants). This will eventually lead to a hollowing out of the economic and cultural base of the region.

By the natural process of popularization, the region is in danger of displacing the functions that originally make it a popular destination, thereby destroying much of the community feel. This exact process can be seen in the Greenwich Village community in New York, which was originally an area very similar to Kensington, but is now notoriously posh. By reducing the diversity of uses in Kensington, you not only eliminate the cultural aspect, but you also significantly reduce the community coherence. Too many retail stores, and you lose businesses that are open late; too few family-run businesses, and you no longer have families living in the area; too little residential density and you further lose the community togetherness.

The Kensington Park (also known as Bellevue Square) is the small inconspicuous park situated in the Southern half of the Market. Its day and nighttime atmosphere are a good measure of the region’s urban health. On any summer day you’ll find this park full of kids playing in the wading pool, young urbanites sprawled across the grass basking in the sun, and all sorts of characters practicing their personal hobbies — tightrope walking, juggling, fire breathing (we have witnessed each of these talents being practiced at least once in this park). But as quick as we are to praise this park during the day, we are just as quick to shun it when night falls. Gone are the laughing children and careless teens, replaced by creepy vibes and shady figures; Kensington’s dark side rears its ugly head. It may seem presumptuous to decry this characteristic of the park; you can argue that this duality is precisely what makes Kensington so unique. But in fact, if left unchecked, these forces are more than just a quirky trait, but rather a threat to what we all love about the area. For the park to become a thriving place at all times of day, the adjacent streets themselves need to be properly integrated with the park area. By increasing the density of late night establishments in the surroundings, you not only increase the traffic of regular people through the park, but you also subsequently brighten an otherwise dark region of Southern Kensington. It would in fact result in a self-reinforcing cycle: as the park becomes safer through use, a more diverse crowd will venture there at all hours, leading to a diverse range of establishments, etc., successfully reversing the trend of deterioration in Southern Kensington.

These ideas alone are no miracle fixes, but rather are founded in the urban design theories pioneered by Jane Jacobs for a thriving neighbourhood.