“Alright, let’s see if I can’t make you something really cool.”

Sameer Mohamed, the owner of Fahrenheit Coffee and Toronto’s top ranking barista at last year’s Central Regional Barista Championship, darts behind his espresso machine and begins fiddling with a series of hidden dials and levers. Moments later, he passes me a latte with an elaborate phoenix pattern on top. I’ve seen a lot of lattes, but Mohamed is good.

Drawn into the crema — that reddish-brown emulsion that covers a good shot of espresso — with stark white steamed milk, latte art is an attempt by baristas to achieve design perfection. The heart, the rosetta, the phoenix, the tulip: there are a few others, but for the most part the lexicon of a latte artist is limited and precise. Confidence and coordination are key; if the steamed milk is poured too slowly, the bubbles on top will remain stuck to the sides of their original receptacle and will never make it into the cup, and if poured too fast, all definition is lost.

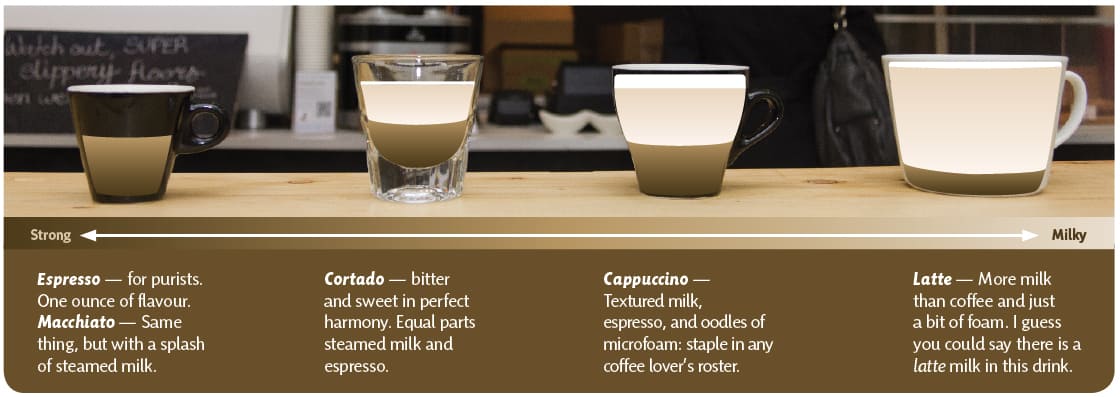

But that isn’t the only challenge a barista faces. Milk scalds at 180 degrees fahrenheit. At that temperature all the bacteria and enzymes in the milk are obliterated, sterilizing that sweet and desirable lactose. The ability to create microfoam — the white bubbly stuff that forms on top of milk with the introduction of heat, air, and movement — is also lost. Without microfoam, latte art is impossible, so baristas have to use all of their senses to predict if their medium is the correct temperature. The metal pitcher holding the milk becomes too hot to hold comfortably when the milk approaches 180 degrees; the surface of the milk takes on a glossy sheen, and the slight whirr of the steam and of constantly moving milk begins to switch frequency to a low ominous growl.

The care and artistry displayed in this preparation reflect the attitude of the high-end independent coffee shop. Mohamed observes that customers “taste with their eyes,” and the unique presentation of latte art adds to their full experience. Despite this view and his own skill at latte art, he is quick to point out that visuals aren’t everything.

“The purpose of latte art to me is basically show that you have good texture in your cappuccino. It’s a showcase for your texture — [it shows] if you’re skilled in the art behind the machine. If you don’t have good texture… your latte art will suck.”

According to Mohamed’s overall philosophy, latte art is a showcase of the product’s quality rather than the product itself. “There’s a lot of importance that’s been given to latte art at the cost of the product; if you can make something that tastes even better than it looks, go for it.”

Mohamed thinks of the independent owner as a designer. “The independent coffee shop is driven primarily by how the [owner] feels about the space. It’s all about how you project yourself into the place.”

He describes how cost, interior design, layout, and location are all choices that must be made by an independent owner to maximize a customer’s experience and the quality of the final product. “Just how a place is laid out can increase output quite significantly. And while you’re doing whatever it is you’re doing, you have to be able to interact with the people in front of the counter. Basically, it generates a nice flow work-wise, and it doesn’t look too cluttered to the customer.”

Mohamed’s keen focus on designing a functional space that produces high-quality products stems from his extensive experience with the coffee world. What started as a part-time gig almost a decade ago in Montreal quickly became a lifestyle. Mohamed took his passion on the road as a coffee consultant under the name Fahrenheit Consulting, helping launch stores and redesigning existing spaces to optimize them for success.

Ultimately, however, the goal was always to launch his own place, which came to fruition in 2011 when he launched the Fahrenheit shop. “Coffee has been a very educational experience for me in terms of its complexity — how much you can change the dynamism of coffee and how incredibly delicate and complex it can be. For some reason, I think it’s a mission of mine to open people’s eyes to this amazing world if they aren’t aware of it.”

As I gulp down my latte, I think about what the implications of uniquely designed shops like Fahrenheit signify for the future of coffee culture. While maybe of a higher calibre than most, Fahrenheit is not entirely a unique breed in Toronto.

These days, we treat coffee less like a commodity and more like a luxury item, like wine, which has led to a surge in small independent coffee shops dedicated to high-quality product. Sure, this trend may bring about higher prices and a sometimes impermeable layer of pretension, but for the most part, it brings better design and damn good coffee. I scoop up the last remnants of my latte’s microfoam from the bottom of my cup and silently recognize that that is not at all a bad thing.