The TIFF Bell Lightbox’s latest retrospective Poetry of Precision: The Films of Robert Bresson goes to show that the roots of true auteurism in cinema are firmly set in France, with the irreplaceable talents of Robert Bresson. Notoriously guarded about his personal life (historians are not sure of Bresson’s actual date of birth), Bresson quietly passed away in 1999 at the suspected age of 99. Nearly 33 years after his last film, we celebrate this artist-cum-director for his profound ability to represent his spiritual doctrine in a way that translates remarkably well to film.

Bart Testa on A Man Escaped or: The Wind Bloweth Where it Listeth

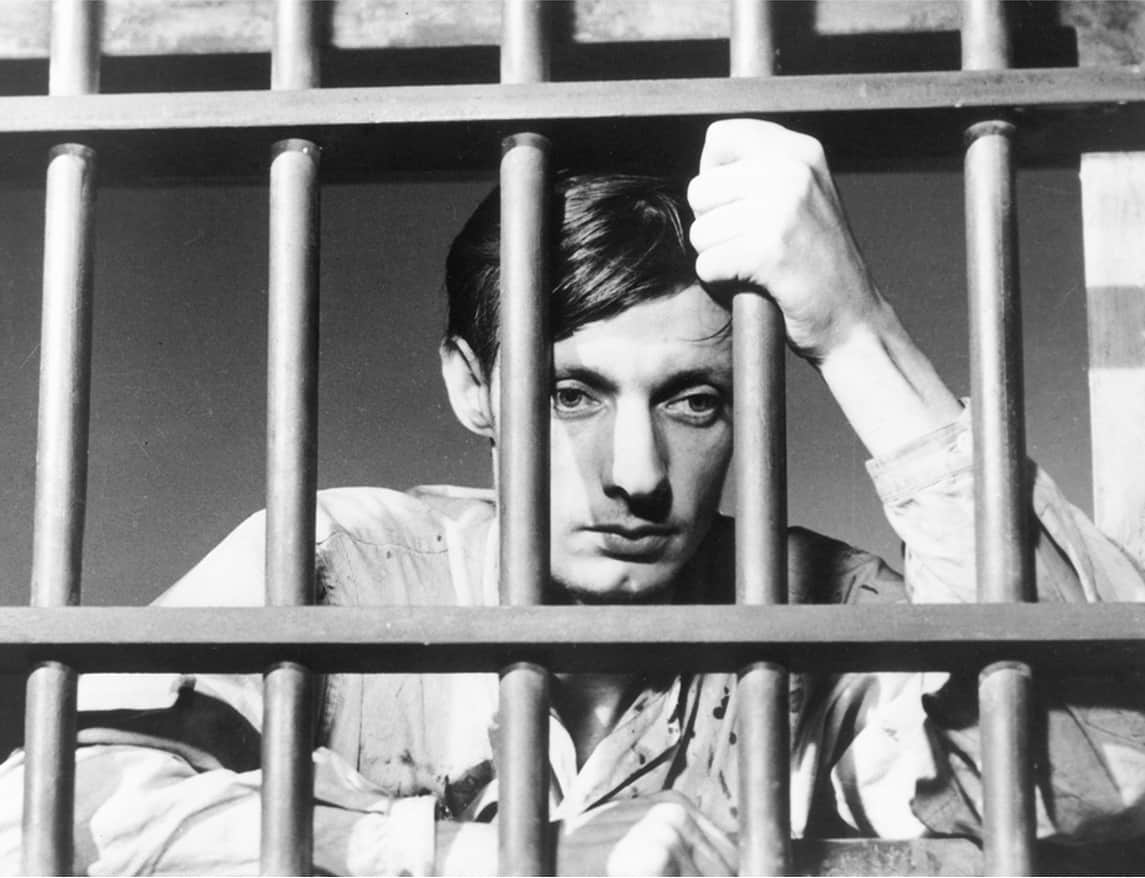

In a special introductory screening to Bresson’s 1956 transcendent prisoner-of-war piece A Man Escaped or: The Wind Bloweth Where it Listeth, University of Toronto professor Bart Testa addressed a packed theatre to explain why we should honour both the film and Bresson’s pioneering sensibilities. Although Bresson’s Escaped is based on the memoirs of French resistance soldier Andre Devigny, Bresson himself also spent time in a German POW camp during WWII, which may be why Testa describes Escaped as the definitive example of Bresson’s films. He likens the meticulous pace, of a “precise style that devotes itself to repetition and narration,” to the filmmaker’s affinity to translate complex feelings and sensibilities on screen.

“Freedom, flexivity, rigour all exist in literature,” Testa explains, “and Bresson brought these [feelings] to the screen.” Escaped is undeniably bleak and lacks an emotional charge one might associate with the life of a prisoner. Instead, we adopt the dauntless, straight-faced desire for freedom that drives Fontaine, the film’s protagonist. We come to be as brave as Fontaine but soon find ourselves sharing also in Fontaine’s sober panic which Bresson achieved in his advanced use of sound. Whenever Fontaine hears the jingle of keys, fast-paced footsteps, or other ominous noises, Bresson enacts a Pavlovian-like response of alarm from both the protagonist and viewers alike. Fontaine stands out as the only prisoner actively trying to pursue freedom, while others such as a Protestant priest (Rolan Monod) passively wish for God’s divine grace to deliver them from captivity. Testa describes this as the greatest struggle in Escaped: the active title, Escaped, and Fontaine’s perseverance juxtaposed with the passivity in the haunting message that “God’s grace cannot be summoned by prayer or action, it cometh and goes — it bloweth where it wills.”

Possibly the most compelling aspect of Bresson’s auteurship is the director’s desire to remain in the shadows. Testa explains that “[Bresson] didn’t engage with people, he had no interest in developing a school of acolytes” and furthermore, that “he was powerfully protective of his private life … we don’t know anything about his personal, religious, or political inclinations — none of that. He was completely terra incognita.”

—Brandon Bastaldo

Brian Price on Lancelot du Lac

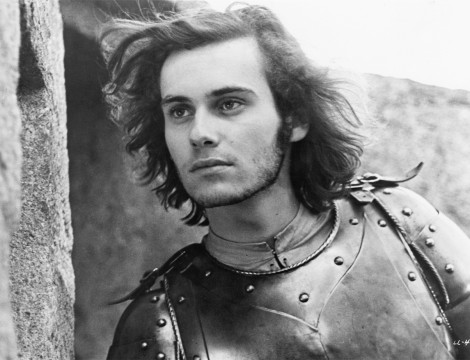

Robert Bresson’s sympathy for youth culture is striking in Lancelot du Lac, a film that re-imagines the story of the Arthurian legend. The film picks up where the legend left off, with King Arthur’s knights returning home after a failed mission to find the Holy Grail.

Brian Price, associate professor at the Department of Visual Studies at U of T, provided an insightful introduction before the film’s screening at the Lightbox to new and well-acquainted fans alike. Price describes the film in terms of semiotics: “The problem of recognitions in Lancelot appears in many ways,” meaning that in order for Lancelot to “see signs, [he has] to be oriented to see them.”

Bresson greatly undermines Lancelot’s “honourable” intentions, and those of his compatriots, by emphasizing the immoral turn an originally noble quest has taken. Fuelled by a desire to display bravado (moreso than any sense of obligation to the lord they claim to serve), the Knights of the Round Table abandon their teachings to further their own interests. Bresson’s Catholicism, a French strain known as Jansenism, is as relevant here as it is in any of his features. It manifests itself in the way Lancelot seems to give himself over to his fate. Urged by fellow comrades to retaliate against naysayers, the glorified knight instead turns away, staving off battle until it is too late.

Price points out that the audience is similarly deprived of recognition — faces are kept anonymous by bulky headgear and key battle scenes are decipherable only by off-screen sound. It’s actually quite easy to miss the final battle scene if your mind is wandering. The piecemeal battle sequence translates into arbitrary shots of injured knights, repeated scenes of a roaming horse, images of arrows piercing trees, and misplaced sounds of clashing swords. Deprivation of such basic knowledge and visible human expression are Bressonian hallmarks. The use of colour and colour patterns is another distinct feature of Lancelot. Bresson’s primary palette of hues is a device in itself, distinguishing the knights from one another and setting the tone of each scene. With the knights’ outdoor tents tinted with a red filter and the unsettling sounds of whinnying horses, the audience can’t help but dread the tragedy that is undoubtedly lurking.

Bresson tried to make Lancelot du Lac in the 1950s, but he was unable to complete the project until 1974, a fact that highlights Price’s assertion that Lancelot is a film about revolt — a skeptical view of revolt that can be aligned with Bresson’s feelings about the May ‘68 riots. Many regarded the student revolts throughout France to be a failure, and Lancelot du Lac acts as the medium through which Bresson can reflect on and think through these important historical questions.

—Damanjit Lamba

Poetry of Precision: The Films of Robert Bresson runs at TIFF Bell Lightbox until March 30. See more coverage on the

retrospective at thevarsity.ca