The recipe is simple: friends meet over food, satisfying their biological urges while talking, ambitions and insecurities are thrown into the mix, and by some magic, the inertia that often dampens human imagination is overcome. The place can be any place, as long as it is one — cyberspace will not do. You need physical proximity for the ideas to flow. Toronto has its share of legendary nooks and crannies, where quintessentially Canadian narratives have emerged.

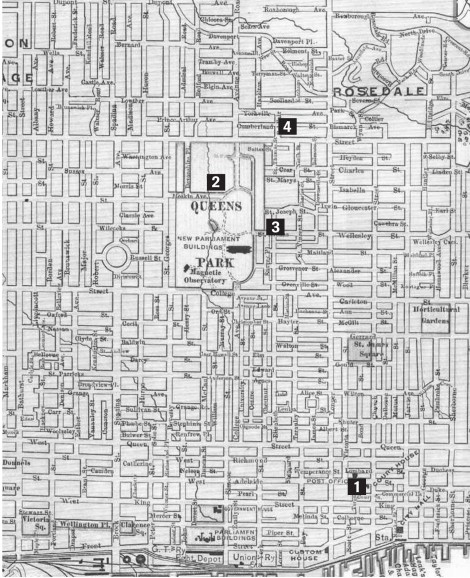

1: 1908: The Group of Seven

36½ King St. East

The room above the Brown Betty Restaurant

Suppertime

“Toronto has arts, but no Art,” says a man in a little room of yesteryear, above the Brown Betty Restaurant on King Street. Others listen on over their steak-and-pancake portions. Art and patriotism spew out between mouthfuls as they encourage each other to speak against the artistic constraints of European naturalism. In attendance are J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, and Tom Thomson, who met as commercial artists working at the design firm Grip Ltd. They share a vision: Canadian artists should organize and find their own direction to express the unique territory of this young country. From here they begin taking weekend trips to Algonquin, Algoma, along the Georgian Bay, developing a style that will mark their future fame as founders of the Group of Seven.

2: 1952: The Toronto School of Communications

100 Queens Park

Basement coffee shop in the Royal Ontario Museum

Most weekdays, 4 pm

A group of friends gathers most weekdays at the coffee shop in the basement of the Royal Ontario Museum. Among the regulars are the anthropologist and filmmaker Ted Carpenter, the artist and curator Harley Parker, the political economists Harold Innis and Tom Easterbrook, and the then little-known English professor Marshall McLuhan.

They converse freely and throw around theories about radio and television. They suspect that these disruptive new media technologies are having an effect on society as well as the psychology of individuals.

This decade-long interdisciplinary exchange of ideas culminates in the publication of The Gutenberg Galaxy by McLuhan in 1962, which popularizes what comes to be known as the Toronto School of Communications. In The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan follows the work of Innis in positing that not only radio and television but all forms of media — especially print media — influence how we view the world through our senses.

3: 1963: Centre for Technology and Culture

39A Queens Park

Coach House, St. Michael’s College

Mondays, 7 pm

The coffee shop group receives an official home with the establishment of the Centre for Technology and Culture. Students flock there every Monday night as McLuhan hosts a seminar in “open mic” format, where ideas bounce around an increasingly star-studded crowd: the likes of John Lennon, Pierre Trudeau, Woody Allen, and Buckminster Fuller. McLuhan offers up koan-like “probe” statements (“The medium is the message!”) designed to provoke discussion and expose the role of electronic media in everyday existence.

Overdue international recognition is given to Toronto’s intellectual community, long populated by luminaries such as Northrop Frye, McLuhan’s long-standing rival. After his popularity wanes in the 1970s, McLuhan’s work is rediscovered with the advent of the Internet, a development which he had anticipated decades in advance.

4: 1965: Hippie-filled Yorkville

134 Yorkville Ave.

The Riverboat Coffeehouse

Nighttime

In the 1960s, Canadian musicians hailing from places like Orillia and Regina — many of whom would later achieve international fame — were incubating in cheap-to-rent row houses in Yorkville. Bohemian types formed a lively artistic community, and folk-singers were hosted at the numerous coffeehouses (one popular spot being The Riverboat) and art galleries that lined Yorkville Avenue.

If you knew what you were looking for, you could catch a pre-fame Joni Mitchell busking in the street, Gordon Lightfoot playing to customers at Fran’s, or perhaps even The Mynah Birds, featuring both Neil Young and Rick James. These future singer-songwriters would also gather to the south on Yonge Street, where blues and rock bands — such as the future members of The Band — were playing in taverns like Le Coq D’Or and The Zanzibar.

In 1965, the musicians in Yorkville did not have a sense of being a “movement” in Canadian music. They were simply perfecting their craft together, making ends meet, and nursing their grand ambitions.

By the 1970s, the low rents which had attracted coffee shop owners to Yorkville in the first place began to rise as developers bought up housing on Yorkville Avenue. As the Yorkville scene disintegrated, musicians sought better opportunities in America. It is during this period that Canadian folk and rock music broke into the American market for the first time, beginning with The Guess Who (with “These Eyes” in 1969) and Gordon Lightfoot (“If You Could Read My Mind” in 1970), followed by Neil Young (as part of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young) and Joni Mitchell (culminating with her critically acclaimed album Blue in 1971).

***

Online exclusive

1925: The Arts and Letters Club

14 Elm Street

The Great Hall of the Arts and Letters Club.

Mealtime

On another evening, this one coloured by the sounds of J. Humfrey Anger tinkering on the spinet and always a debate, Wyly Grier (who will later become the first Canadian to be knighted) proposes that the meetings be named the “Arts and Letters Club.” The men agree. In 1925 (after a couple of evictions) they find a home at 14 Elm Street. Here, A. Y. Jackson (of Group of Seven fame) will bring his friend, Frederick Banting, a reticent scientist (who only a few years earlier helped to discover insulin) trying to evade the media hounds still lurking about the University of Toronto.

The Arts and Letters Club will over time entertain the likes of Robertson Davies, man of letters, and the creator of CBCʼs The National, Mavor Moore.

2008: The Toronto hip hop Renaissance

15 Fort York Blvd, Apt 1503

Noah “40” Shebib’s bedroom studio

Midnight

Noah “40” Shebib is up late producing a beat in his bedroom studio. His friend Aubrey “Drake” Graham, still an unknown rapper, arrives late at night, carrying with him champagne, debt, and family problems. He needs to vent his frustrations, and 40 knows Drake well enough to instinctively craft a musical space which puts him in a zone to express himself. Drake and 40 serve as each other’s foils, and have arrived at this point of creative harmony after finding each other amongst Toronto’s vibrant hip hop community.

In 2004, many of Drake’s future posse could be found in the orbit of Toronto hip-hop figure Noah “Gadget” Campbell, including 18-year old producer Matthew Samuels (known as “Boi-1da”) who would produce Drake’s first hit, “Best I Ever Had” in 2009. Drake’s Toronto mix-tapes would catch the attention of New Orleans rapper Dwayne “Lil Wayne” Carter, who signed him to his record label and gave him access to valuable industry connections. Despite these new resources, Drake chooses to continue to collaborate with his inner circle. His niche sound (a somber R&B combined with hip hop) is born out of the unguarded atmosphere created in the studio during late nights of improvisation with his producers 40 and Boi-1da, where they goof around and share their favourite music with each other.

Drake’s creative team October’s Very Own (composed primarily of old friends) seeks to develop local talent, enlisting young artists like Hyghly Allenyne and Lamar Taylor (who direct Drake’s music videos and design his album artwork), singer Abel Tesfaye (also known as “The Weeknd”), and the producer Tyler “T-Minus” Williams. He is consciously building up the community and infrastructure that nurtured him early on, and setting up the foundations for himself, his collaborators, and Canadian hip-hop’s future success.