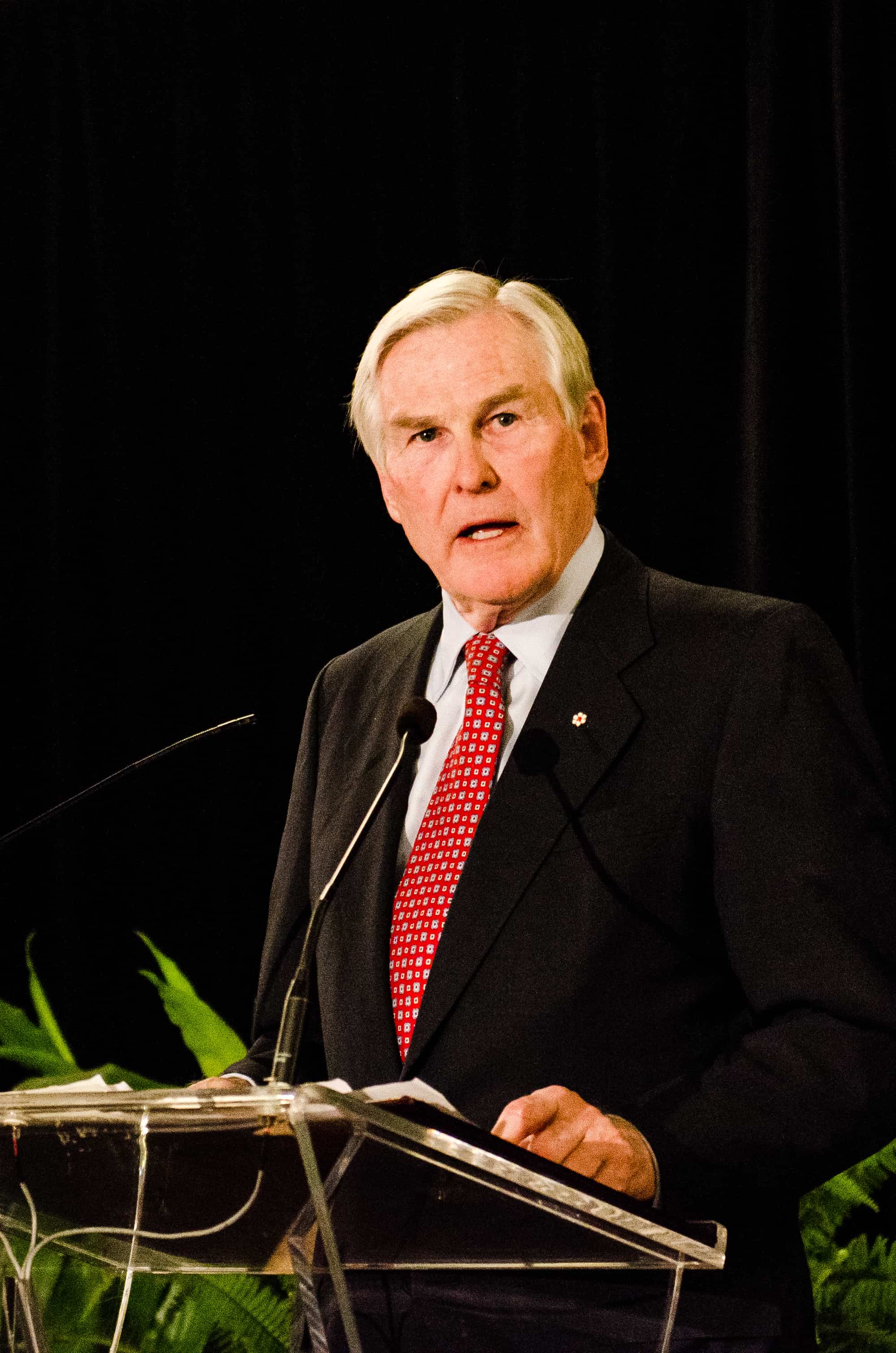

In one of his first public speaking engagements since his appointment as chancellor of the University of Toronto, former ambassador to the United States and ex-finance minister Michael Wilson spoke at Hart House last Wednesday.

Wilson, who was invited to speak by the student-run Hart House Debates Committee, discussed Canada–US relations and the potential outcomes of the November 6 election between Mitt Romney and Barack Obama for about 45 minutes, speaking to a capacity crowd in the Great Hall. Wilson served as ambassador to the United States from 2006 to 2009.

For the most part, Wilson painted a rosy picture of cross-border relations. “I would say that the current relationship with the United States is very good,” he said. “Prime Minister Harper and President Obama have a good personal relationship, the chemistry is good, they talk frequently and they meet at a variety of international events.”

“There are no burning, high-profile controversies, nothing causing us any real difficulty here,” said Wilson, adding that Canadian involvement in Afghanistan and more recently in Libya have also garnered significant diplomatic good-will.

“I don’t think that there will be a lot of difference between a President Obama and a President Romney,” predicted Wilson. “Romney is much more familiar with Canada than Obama, but on the other hand, a Romney administration might have some of the hardliners that I had to deal with when I was in Washington [under George W. Bush].”

Wilson also offered some inside knowledge on current issues.

The controversial pipeline Keystone XL was the focus of many attendees’ questions. Although President Obama declined to approve the pipeline’s route in January, a final decision was punted to beyond election day. The decision is, in Wilson’s estimation, “quite likely to be reversed.”

“Romney is absolutely going to [reverse the decision] and the vice-presidential candidate has said that as well,” said Wilson. “Quietly, we are getting that same message from the current administration.”

Wilson says the furor surrounding the pipeline has led Canadian business leaders and the federal government to take “a long, hard look” at energy relations between the US and Canada. According to Wilson, there is a growing realization north of the border that a critical decision like Keystone was “dependent on [American] domestic politics” and the Canadian energy sector was “held up to ransom for political reasons” because the United States was “effectively our only customer.”

Wilson also suggested that the consensus many were reaching is a pivot towards potential customers in Asia, although he also stressed that such a pivot would not detract from the strength of US-Canadian relations.

Discussing the border agreement signed a year and a half ago, Wilson hinted that it might undergo some alterations in the aftermath of the election. Wilson said he was told that specifics about the changes would have come this past summer, but due to some “awkwardness” there will be nothing forthcoming until after Americans have gone to the polls.

Wilson discussed a range of other topics, including impending free trade agreements — he said he believes the Trans-Pacific Partnership will succeed, along with an agreement with the EU, making Canada the first country to trade freely with three distinct trading blocs — the new Detroit–Windsor bridge crossing, and how best to “reinvigorate” the security relationship after successes in Afghanistan and Libya.

TV: Describe your job as chancellor to a student that doesn’t know what it is exactly that you do.

MW: The chancellor’s position is the most senior position in the alumni. My job is to be the broad link to the alumni, all 500,000 of us, in many countries around the world. I’m also a link to the students. At Convocation, I’m the one handing out the degrees. I think the chancellor in some ways has a responsibility to convey to students what the university is, and what it can mean to students. This is the largest university in the country, it is arguably the best university in the country, it has a very high calibre of faculty members, very high calibre of students, a record of research successes across a very broad range of disciplines. And our alumni are leaders in many different fields in this city but also in the province and in the country. We are fortunate to have outstanding students, but I feel it is in some ways my responsibility, when I have the opportunity, to remind students that they are fortunate to have that experience of being in a lively place intellectually and academically, but also lively in terms of culture, sports, different nationalities. Canada has already begun to appear more and more global in our orientation. This is a great place to start developing that global orientation.

TV: You’ve been an spokesperson for a group that promoted public-private partnerships. What do you think is the role of the private sector on university campuses?

MW: That group’s efforts were more related to infrastructure. After the election in 2003 [fought largely over the role of the private sector in two hospitals], both the Liberals and the Conservatives recognized the private sector’s role in the partnership was to finance, design, and build a building according to the requirements of the public sector. The management, the operation, all the medical activities, that was the responsibility of the public sector, not the private sector.

I say to universities or hospitals or transportation departments: why do you want to have your money tied up in bricks and mortar? Shouldn’t you let the private sector own those things, and have them financed in ways that are more appropriate to their interests (pension funds, life insurance) financing those fixed assets long term.

So it’s what goes on in the asset that’s important, not what the asset is. If we’re going to put a new building somewhere, should that be owned by the university? In my judgment, there’s got to be a very strong reason why the university would want to tie their money up for 40, 50, 60 years in a fixed asset. But the university has got to be totally in control of what goes on inside that building. That’s the distinction.

TV: Do you feel like online education has the potential to disrupt the traditional model of bricks-and-mortar universities?

MW: I’m not an expert in online learning. But I see online learning as a way for us to expand on what the university can deliver through its fixed assets on campus. If we can take courses to people that are working 8 hours a day and have a family, they can go online and improve on their own education. I say that’s terrific. If we can take online learning to more rural communities and teach people in those communities some of the skills they haven’t been able to learn, or those that didn’t have the resources to move away to university, again, I think it’s a terrific way of expanding the reach of education. The more we can expand that reach, the higher our standard of living will be.

TV: You’ve been a longstanding advocate for mental health issues. A recent report in Maclean’s detailed what appears to be a worsening situation when it comes to student mental health on campuses all across Canada. How do you stand on this issue?

MW: I’ve spoken to both the AUCC and the Association for Community Colleges on this very point. One of the points I make is that when students come from high school, they’re in classes of 25 people. They know practically everybody in the classroom, the teacher knows everybody. Then they move into a much bigger community and they get lost in the crowd. Universities and colleges have got to find ways of making sure that people don’t get caught between sources of support, between the cracks so to speak. If you have a buddy and you suddenly realize he’s not coming to class, he’s getting a little lethargic, he’s losing interest – well, you can give students a sense of responsibility that if a good friend of yours is starting to demonstrate these types of personality changes, find out a little bit about them. If he started limping, you’d be asking: ‘what’s the limp for? Should you go and see a doctor, get that put into a cast?’ You wouldn’t think twice about that. But because it’s happening in someone’s head, you tend to shy away from that. You’ve got to get the sense that you shouldn’t shy away, but reach out and help a friend that appears to be suffering.