Over the past year, the walls of the AGO have proudly hosted the works of Chagall and Picasso, two major modernist artists. This fall, the gallery has opened its doors to two more modernist icons: Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. “Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics and Painting” is an exhibition that celebrates what AGO director Matthew Teitelbaum calls the artists’ “commitment and conviction” to politics and art.

The AGO’s previous retrospectives of big name artists have explored the Russian avant-garde and Picasso’s Paris. This new exhibition explores Mexico as a cultural centre, although in reality, its presentation of a nation’s artistic identity is dwarfed by the work of a feisty female artist whose biographical tribulations take the spotlight.

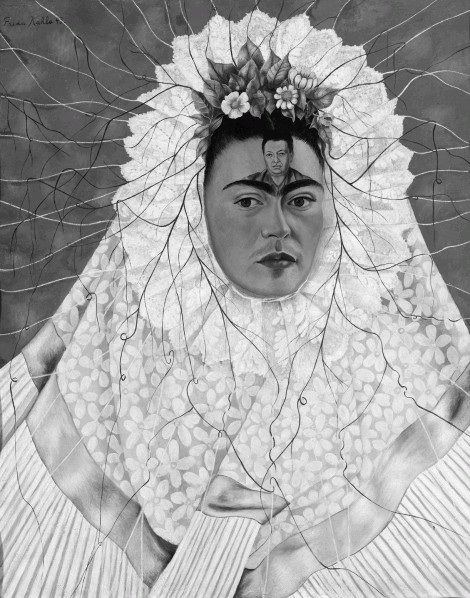

Self Portrait as a Tehuana (Diego on my Mind), 1943. FRIDA KHALO

According to the curator, OCAD professor Dot Tuer, the works of Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera are “rarely paired together in an exhibition,” probably because the subject matter of their oeuvres differs greatly. Rivera, a fervent communist, captured the history and politics of Mexico in the early twentieth century, while Kahlo focused on the subject she claimed to know best: herself.

During my recent visit to “Frida & Digeo,” it was easy to see that the exhibit’s focus lies on the tragic life of Kahlo, whose body was crushed in a streetcar accident in 1925, when she was only eighteen years old. The physical ramifications of the accident haunted Kahlo until her death, and had an all-encompassing and significant influence on her art. Many of Kahlo’s violent paintings are featured at the AGO, including Few Small Nips (1935), a small painting that shows a woman lying naked and bloodied on a table with a man standing over her. As I viewed the painting, I could overhear a number of spectators commenting on its association with Frida’s tragic experiences, including the many miscarriages resulting from the accident that rendered her infertile. Visitors were clearly more interested in the private life of this troubled personality than they were in the grand political murals of her husband.

To be fair, Kahlo’s dark and personal portraits usually do outshine Rivera’s works, and not only within the walls of the AGO. “Frida & Diego” features many of the self-portraits that have made Kahlo a household name, including Self-Portraits with Monkeys (1943). The vibrant colours and jungle backdrop of the painting are all part of Kahlo’s signature style, which continues to claim an iconic place in pop culture to this day.

While Rivera’s work has taken a backseat to his wife’s art, “Frida & Diego” suggests that this was not always the case. Rivera was once the more renowned artist of the two, as famous for his murals as he was for his womanizing. The AGO’s exhibition opens with a room full of his cubist paintings. I was surprised to discover that these fragmented landscapes and still-life paintings were the product of a Mexican artist, although they were admittedly painted while Rivera lived in France. As I walked along the display of Rivera’s work, which is arranged according to medium, I became more aware of the variety of his paintings. “Frida & Diego” displays Rivera’s impressive mastery of a range of styles, and his body of work includes something to suit everyone’s tastes.

As with many exhibitions at the AGO, “Frida & Diego” included an important interactive portion to the exhibit. Starting on October 24, visitors will have the opportunity to leave notes on an ofrenda — a traditional shrine that welcomes the dead — constructed by Mexican artist Carlomagno Pedro Martinez. This portion will be included in the final room of the exhibition, which features large papier-mâché figures of Kahlo and Rivera created by Toronto theatre group Shadowland.

Photography also plays a large part in the exhibition. Tuer notes that photography was “essential to the way Frida Kahlo created her persona.” Mid-way through the exhibition, there is an entire room dedicated to photography and video footage of Kahlo’s photo-shoots. Two walls feature black and white photography, while a third wall boasts coloured photographs taken by Kahlo’s lover and friend Nikolas Murray.

Most of the photographs in this portion of the exhibit are of Kahlo, and they evoke her colourful and virbant paintings. Yet a photograph by Bernard Silverstein, entitled Frida Paints Self-Portrait while Diego Watches (1940), suggests that while Kahlo’s work may have eclipsed that of her husband, their artistic lives were intricately intertwined. Perhaps, as Martinez (designer of the aforementioned ofrenda) has suggested, Rivera was a supporter of Kahlo’s art and her life source after her accident. With this in mind, it is appropriate that the work of these two artists are displayed together in this beautiful and provocative exhibit at the AGO.