In early cinema, night was a creation. Cameras couldn’t shoot outside without daylight, so the typical solution would be to use “Day For Night” techniques: darkening a shot by under-exposing it or using a blue filter on the lens. The sole requirement was to be believable to the viewer. Moviemaking, after all, is just a big ruse.

When shooting at night became possible, night became an area of potential for films; not only as a context, but as a subject unto itself, one to be variously explored, felt out and framed. It is worth asking, case by case, why a film foregrounds night in the specific way that it does. Why is night needed? Some films have such a need for darkness that if you removed the night from them, all you would have is a slow evening followed by a rough morning, and you wouldn’t know why.

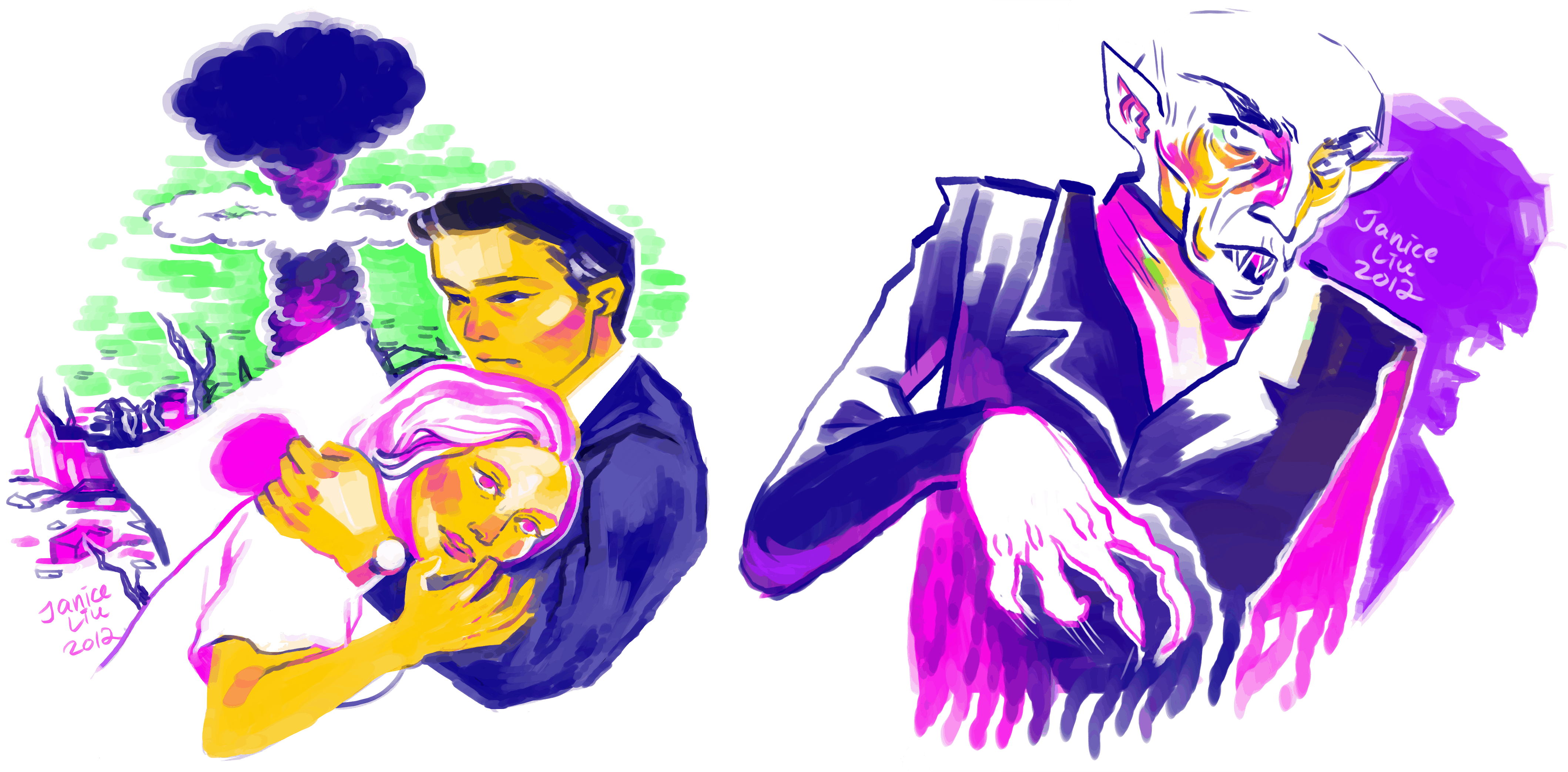

Nosferatu

1922

Even before technological means of capturing it existed, F.W. Murnau took an interest in night and its relationship to fear. Murnau’s Nosferatu, associated with German expressionism, is a silent horror film about a vampire who sets about terrorizing a small town. In today’s culture, vampires can cruise the mall without dying of sun exposure, but we are also familiar with the traditional, gothic vampire, and how necessary night is to him. Nosferatu, the vampire in the film, permeates the night; at his worst, he is a dramatic, lurching shadow, an actual manifestation of darkness. The film makes a dichotomy out of night and day, with Nosferatu’s absolute power on one side and his obliteration on the other. In many prints, tinting and toning the film with a consistent colour signifies night scenes, which is a crucial use of Day for Night; the vampire is immediately invoked and the viewer knows all bets are off. The tints, usually blue or green, have the incidental effect of making night feel appropriately supernatural.

The Big Sleep

1946

Depictions of the threatening night eventually took on human features. Sex, booze, blackmail, murder, Los Angeles — these are some things you can find inside the brown paper baggy of film noir, passed around in Hollywood in the 1940s by directors like Howard Hawks. In his film The Big Sleep, night is the time for vice, and the waking hours for stock characters such as the mobster and the sexually deviant blond. Metaphorically, this world is the corrupt and unseen reality behind idealized Los Angeles. A literal lack of vision, rendered through the sparse lighting characteristic of noir, is also functional to the detective narrative. Throwing things into obscurity means that they are hidden. Uncertainty creates intrigue, identifiable people become dark shapes, the origin of a gunshot is harder to pinpoint, and detective Marlowe is able to gather information without being noticed. In the film, an almost allergic reaction to any light is demonstrated when Humphrey Bogart (famously under-lit) has Lauren Bacall turn off a lamp by saying, “Move that light, will you? Or move me.”

Hiroshima Mon Amour

1959

Night belongs to romance — to Bogart and Bacall, but also to the nameless French woman and her Japanese lover, who spend 24 hours together in postwar Hiroshima. In Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour, night allows memory to push through a desire to forget personal tragedy in the context of global tragedy; it is revealed through brief flashbacks that the woman had an affair with a German soldier during the war, for which she was brutally shamed in her town. What occurs is the opposite of obscurity: exposition. The later it gets, the more detailed her story becomes. She wears white against the darkness and is always illuminated during her narration, while her male companion, prompting her story, is covered by shadow; his anonymity makes him a surrogate for her former lover, and the whole night, a reincarnation. Traveling backward through memory confuses the sense of time’s passage in the present. The unclear temporality reinforces the universally structureless nature of night.

Night on Earth

1991

Jim Jarmusch is a director who appreciates night for its lack of definition because it encourages the imagination. Night on Earth handles after hours with relative simplicity because this is its self-professed theme. It gives continuity to the different segments of the film, which track the experiences of cab drivers in five cities: L.A., New York, Paris, Rome, and Helsinki. These happen in sequence; we feel as if we are progressively moving through the stages of a complete night, but really we are experiencing one simultaneous frame of time, five times over. Because of this repetition, and because the drivers are working their jobs, night quickly becomes normal. “What a fucked up day,” says the Paris driver without a trace of irony after dumping a couple of guys out of his cab. Invariably, there is a pronounced contrast between passenger and driver, which produces situations both comedic and melancholic. Each city’s existing light has a unique quality, so Jarmusch claims to have shot with nylons stretched over the lens, a different type of nylon for each city. The diffusion evokes Jarmusch’s theory of the night: it’s a time that benefits from the absence of hard light and lets creative conversation arise between strangers in a cab.

Werckmeister Harmonies

2000

Bela Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies is an aesthetic study of the end of earth, experienced by a town somewhere on the Hungarian Plain. At the beginning, Valuska, the young mailman, demonstrates an eclipse of the sun in a pub, using the bodies of the drunken men to represent cosmic bodies. In doing so, he invokes “boundlessness” and “infinite emptiness,” the feeling of immortality. The beauty of this sequence is a bitter counterpart in the film’s main theme, which is the conclusion of all life. Night’s presence in the film does not create uncertainty because the town seems aware of its imminent destruction. It begins with a mob of lowlifes who have come from far away to see an embalmed whale in the town square. Later, they march from the square to destroy the homes of the townspeople. People are shown moving purposefully through the night toward a known destination. Tarr does not attempt to manipulate the available light; Valuska’s silhouette walks along the road, and the only light provided by streetlamps. When the camera recedes from him, past the lamps, the frame is dominated by an expanse of blackness.