The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library houses writing as old as Babylonia. While the library may not contain stone tablets, some of its books, like the early antiquarian pamphlets known in Latin as incubala, are more than 600 years old.

Books, unlike iPods and BlackBerrys, have been a medium of information for centuries. We are often told not to judge a book by its cover, but how can you not when the binding is stitched with such care, the title and author’s name written in colourful and intriguing ways? Even the pages of a book can be unique, some trimmed sharp and straight while others are ruffled and soft. The book, regardless of the text found within, is a piece of art on its own, a piece of craftsmanship that should be honoured. Yet, other than the Fisher library, there are no galleries or museums in Toronto dedicated exclusively to the book. So where does one go to see books given the respect they so deserve?

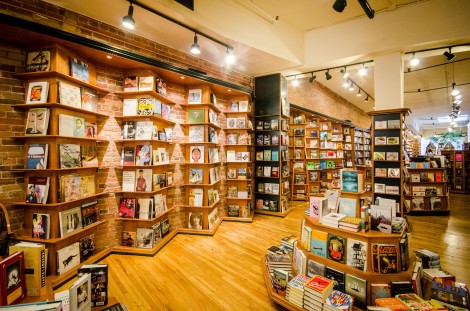

Nicholas Hoare Books. BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

The answer is independent bookstores. By “independent” I mean everything other than Indigo or Chapters. Those big retail stores, while they refer to themselves as bookshops, sell everything from Christmas ornaments to coffee mugs, and are becoming more and more like Walmart in an urban bourgeois disguise.

The little guys, the independent bookshops, are under threat not only from massive chains like Indigo, but because of the recent emergence of the e-book. The book has been threatened with extinction before and people often wonder if it is heading toward the junkyard of obsolete technologies, the home of Betamax and VHS. Thanks to the e-book, we can no longer subscribe to a 1990s fantasy like the one in You’ve Got Mail, in which a lovely independent bookshop is saved by a bookstore chain mogul played by Tom Hanks. Unfortunately, the only way to contact Mr. Kindle is via amazon.com’s shopping cart button.

BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

So with the book’s life endangered and the business dominated by Amazon and Indigo, why are independent bookstores important to the city? How do they survive?

“Not easily,” says Joanne Saul, co-owner of Type Books, a small bookshop on Queen street near Trinity Bellwoods park. “An independent bookstore has to be really grounded in its community.”

Type, a quaint little shop that faces Trinity Bellwoods Park, offers literacy programs for neighbourhood schools, story time for kids, and launch parties for magazines and books. It also houses an art gallery in the basement. Because the surrounding area is home to many artists, writers and designers, the store has a huge collection of design, architecture and fashion books. The children’s section at the back of the store — which comes complete with mushroom-shaped sofas — offers everything from the latest Captain Underpants to regular kids’ classics like Curious George.

BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

Inside the shop you feel the sense of community. The cashier, who also owns a local record label, walks me through their “Plotless Fiction” section and talks about works by authors like Beckett and Burroughs. Another staff member, the editor of an independent fashion magazine, takes me around the shop and talks about the latest trends in children’s lit. She points out a shelf of books labeled “Flora and Fauna,” yet another idiosyncratic section.

While Saul acknowledges the difficulties of keeping her store afloat in an industry dominated by Chapters and Indigo, other booksellers don’t see themselves as being under the threat of big-box retail or online shops. Ben McNally, owner of Ben McNally Books, is one of them.

“I was never concerned with big box retail,” McNally says. “They can’t do what I do. If there is something that I’m specialized in, it’s customer service. That’s another place they can’t touch me. You come in here a few times, I’m going to know who you are, you’re going to know who I am. We’re going to have a relationship… That doesn’t work there in big box. You never know if you’re going to see the same person two times in a row.”

BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

McNally wasn’t lying about the level of dedication and personal attention that defines his customer service. When I entered the shop, he was ordering a cab for one of his elderly regulars.

Ben McNally Books has a fireside, living-room feel. It’s a calming oasis of leather sofas and classical music in the heart of the Bay Street financial district.

During our conversation, McNally acknowledges that poor business decisions were the downfall of newly-deceased Toronto independents like Pages and This is Not the Rosedale Library. Yet according to McNally, the main issue is the customers themselves, who are happy to forego bookstores entirely if they can find a better bargain online.

“You should never buy anything online,” he states with conviction. “It’s cheaper but it’s only cheaper until there is no other competition. Why would Amazon sell you things cheap if they’re the only people selling you that thing? Why would you buy it online? Why would you drive your local retailer out of business? You want your neighbourhood to be vibrant. You don’t want to have nothing but fast food outlets in your neighborhood. Believe me you don’t really want that.”

A few blocks south of Ben McNally on Front Street is another major independent bookstore. Within shouting distance of the historic St. Lawrence Market, Nicholas Hoare is a bookshop that looks like it could be a second home to some of its wealthier clientele. The store is a long stretch of smooth, golden oak floors and sliding ladders, and oil paintings that hang along the walls in fancy frames. The shop looks as though it could have been plucked out of an old-school library.

According to Nicholas Hoare, the owner of this eponymous bookshop, the key to a successful independent bookstore is having a focused and well-rooted clientele.

“Our milieu is not the young,” he says. “It is middle-aged to the elderly. Our crowd is not the teenybopper. It’s not even people in their twenties. We start to see people when their mortgages are paid off, children are going to school, and the expenses are lightening up. The older they get the more we see them. Our milieu, is what we call the blue rinse crowd, which is, very well-heeled, very knowledgeable, extremely seasoned readers who come in knowing exactly what they want… Our market is a little different from the ordinary bookstore.

“The difference is what makes us.”

Hoare emphasizes that his store does not offer discounts, Robert Ludlum or e-books. It demands a high-earning community of costumers. Nevertheless, even poor, scrappy students like myself would probably be unable to stop themselves from browsing the beautiful shop and pretending to be posh.

Type Books, Ben McNally and Nicholas Hoare all have a strong focus on literary fiction, but there are other independents in the city that are far more specialized and still manage to survive. Among them are the comic art shop The Beguiling; the cookbook shops Good Egg and The Cookbook Store; the Bakka-Phoenix sci-fi specialty shop; and Mable’s Fables, the ultimate kid’s bookstore.

So to return to those initial questions, why are independent bookshops important and how do they survive?

Hoare provides a succinct answer: “If customers look at independent bookstores as a fount of wisdom and not a fount of evil, they’ll go down there and [be] ready to pay for the books that they appreciate. The key here is curating.” Hoare himself claims to buy all his books based on merit, purchasing only works that get rave reviews.

Regardless of their individual marketing ventures, it is independent bookstores as a group that are putting well-made and well-written books on display. In front of windows and on smooth wooden tables, bookshop owners are providing their customers with a gallery; a gallery not of paintings or fossils, but of books, which have been carefully curated and honoured as they should be.