The nervous period of settling into university has long since passed for this year’s crop of first year students. In its place, the ongoing recruitment of high school students and the influx of thousands of applications begins to provide definition to the 2013 incoming class, assisted by the university’s fall campus days, residence tours, academic information sessions, university fairs, and “Boundless” campaign. Having escaped the endless succession of recruitment events a mere five months ago myself, it seems clear that the university needs a new approach.

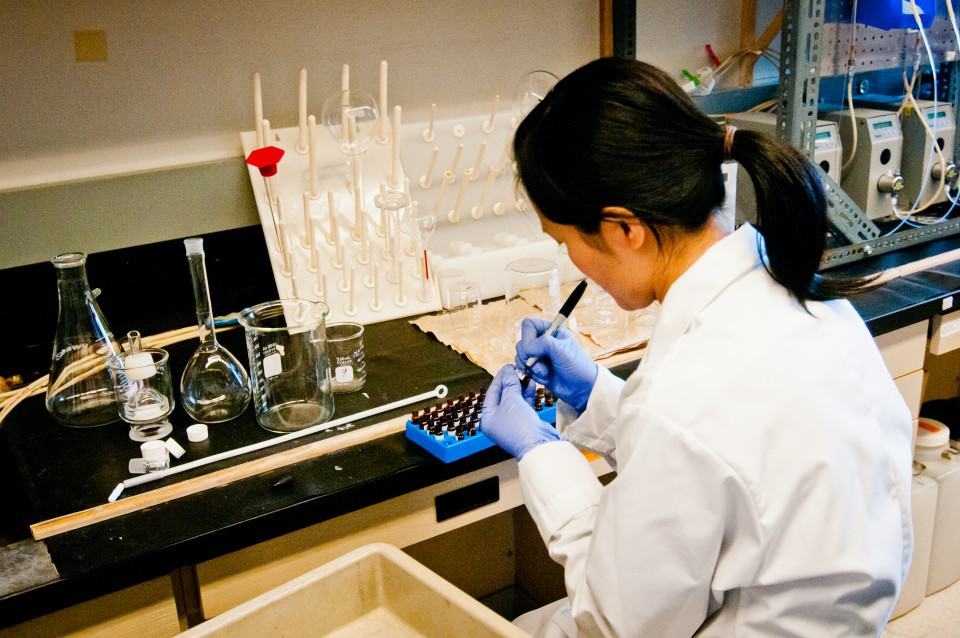

With a student population that is only 23 per cent female, U of T’s Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering needs to attract female students to generate a more balanced student base. The move to attract female students extends beyond engineering into general sciences at the university. Should the university enact recruitment events and programs to attract female students? Absolutely — unlike other elite schools such as MIT, the gender profile of applications to U of T closely reflects the final composition of the class, suggesting that merit rather than gender is the primary consideration in granting admission. Artificially creating a class of equal male-female composition would be the equivalent of enacting a reverse-discrimination policy. But the question remains: is U of T taking the right approach to recruiting female candidates to science and engineering?

The Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering employs distinct approaches to attracting female students to fulfill two goals: attracting applicants and securing enrolment. Attracting applicants consists of targeting high school students through summer programs such as DEEP Summer Academy for grades nine to 12 and Jr. DEEP program for grades 4 to 8, plus extra-curricular programs, including the Saturday Science and Engineering Academy. These programs and several additional events have a female focus. Whether in the form of a Girls’ Jr. DEEP, Girls’ Science and Engineering Saturdays, the Skule Sisters program, or ‘Go ENG Girl’ events, the faculty has translated its goal of increasing female enrolment into action. How? By changing the attitude of female students toward a stereotypically male discipline, providing female engineering role models, and demonstrating the potential that girls have to achieve their career dreams through engineering. These programs serve their purpose. Their impact is felt long before girls consider applying to university, and U of T establishes a name for itself in the prospective student pool.

At the other end of the spectrum, the race to secure enrolment overtakes recruitment goals. At this point, following arduous physics courses, lengthy applications, and a tedious waiting period, the acceptance letters have already been sent out. But the goals of female students also change. No longer is male-to-female ratio a factor. A student who has put energy and time into obtaining the necessary prerequisites, applying, and attending a post-acceptance recruitment event is seeking more than merely a confirmation that there are female engineering students at U of T.

Rather, the final questions that a potential student has concern academic success, the sense of community at the university, and costs. So when the university holds a “Girls Leadership in Engineering Experience” event three days before the final deadline for decision acceptance, attempts to entice female candidates fall short. “The sense of community and closeness to home were what contributed to my final decision [to enroll],” said event attendee and first-year student Michelle Kirk. “Gender didn’t factor into that.”

If engineering recruitment is a case study for recruiting girls into the sciences, the solution is clear. Pre-university recruitment is important — reversing deeply-rooted stereotypes about female participation in the sciences is necessary to increase the number of female applicants to any science program. But the mission to increase female enrolment ends there; registrars would spend time and resources much more wisely if they organized pre-enrollment events that weren’t gender-specific.