“If you take a picture of the University of Toronto, you take a picture of University College,” says Donald Ainslie, principal of University College. “UC is, in some sense, synecdochical for the university: it’s the part that stands in for the whole.”

In his office, surrounded by relics of the rich heritage of University College — old photographs, pieces of the burnt rubble from the famous fire of 1890, the purported skull of Ivan Reznikoff — Ainslie expounds his plan for UC’s future interior.

Donald Ainslee stands in a to-be-renovated section of UC BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

“One of the things I discovered in my first year as principal was that we had far too much empty and underutilized space. I started to think about what we could do to make sure that students get the most out of what University College has to offer,” he says. Ainslie became principal of the college in July 2011, having previously served as chair of U of T’s philosophy department.

The UC building, a designated Canadian national historic site, opened in 1859 and was last renovated in the 1980s.

“It’s an institution that’s welcoming, that’s respectful of our longstanding, non-sectarian history and our history of openness, taking students no matter what their religious or ethnic background. This helped to focus a discussion of the space: how do we make the building embody that which UC is about?”

Ainslie explains that the project is guided by four principles, decided upon through consultation with faculty and students: “To embody the college’s commitment to education and research; to make sure this commitment focuses on undergraduates; respect for historical heritage; and accessibility.”

Students and faculty have been supportive throughout the process. “Students have been involved throughout and I’ve heard pretty much only supportive words,” Ainslie said.

The University College Literary and Athletic Society (UCLit) has enthusiastically supported the proposed renovations.

“It’s a beautiful building that we all love and I don’t see anything negative about trying to maximize its use,” says Ben Dionne, president of the UCLit. “The biggest concern has been that it’s going to happen when people are graduated. Overall, people are very enthusiastic about the project.”

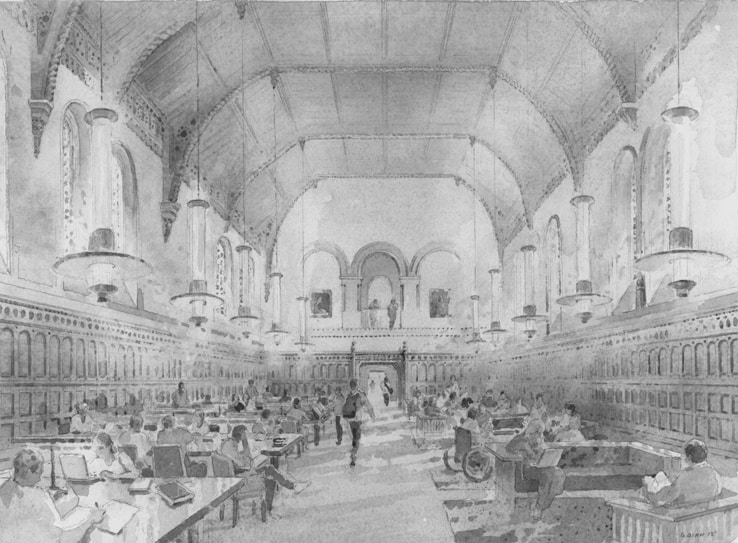

A key project in the proposed restoration will be relocating the Laidlaw Library. The 33,000-work collection will be moved to East Hall to become the new University College Library, and Laidlaw’s current space will serve as a large classroom or event space.

Although a few fans of Laidlaw are disappointed with this plan, the library goes largely unused, regularly sitting empty.

“This idea came partly because of a fortuitous circumstance. East Hall was originally the library of the university with a mezzanine that housed about 33,000 works,” Ainslie explains. “Why not solve the problem that East Hall sits empty and solve the problem that the library isn’t working for our students by returning to the original purpose of East Hall, being inspired by this history and reconstructing a twenty-first century library in a historic space?”

The architecture and design of the library will invoke the original space, reconstructing the mezzanine over the stacks, and using columnar lighting inspired by the kerosene lamps originally used throughout the college, one of which caused the devastating 1890 fire that burned the College to the ground.

Other proposed renovations include converting West Hall to a multi-purpose space, revamping and modernizing UC classrooms, and adding a café to the third floor, likely in partnership with beloved UC institution Diabolos.

While Ainslie intends to fix floors and desks and bring in new technology as part of his plan to modernize the lecture halls, he also wants to uncover hidden historic features to reveal and highlight the heritage of the building.

Accessibility, one of Ainslie’s central tenets for the restoration, is a critical issue in the college as it stands.

“We pride ourselves on being the open college … and yet if you can’t handle stairs, it’s a very difficult building. If there’s a class with any kind of mobility problems, we will move the class. We can’t accommodate the student’s needs and it shows that we failed to meet our sense of ourselves as the welcoming college. We’re trying to build accessibility into all the projects,” Ainslie explains.

Dionne expressed concern about accessibility as well. “To get in the college right now, you need to go all the way around, and take the elevator at Laidlaw Library.”

Dionne expressed concern about accessibility as well. “To get in the college right now, you need to go all the way around, and take the elevator at Laidlaw Library.”

To address this need, an elevator will be placed in the centre of the building, and a new wheelchair-accessible entrance will be constructed behind Croft Chapter House.

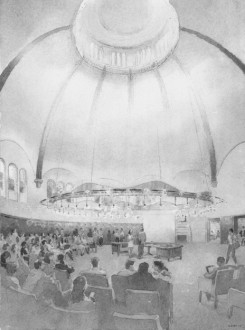

Croft will also undergo a facelift under the proposed plans. The aging space will be renovated into a modern conference room with improved lighting for research events and meetings of the UCLit. It will be linked to the Senior Common Room with additional entryways.

The University College quad will undergo changes, with lighting and outlets to allow for more events to occur in the outdoor space. A new air conditioning system will be introduced to the college, meaning that the large AC unit in the corner of the quad will be removed. In order to increase traffic to the patio surrounding the quad, a slope will be added on the east side to connect the quad on all sides. Renewed vegetation and a water feature will also be added.

The cost of the plan remains unclear. Ainslie intends to fundraise through the ongoing university-wide Boundless campaign. University College fees are determined by students, and therefore are unlikely to be impacted by the restoration, though there is some discussion within the UCLit about asking students to contribute modestly to the campaign.

“There is some talk about trying to pass a referendum to get a project levy,” Dionne explains. “It’s still in discussion, but we are thinking about asking students to throw in a small contribution. This would bring some money, but also show possible investors that the students are behind it.”

Ainslie believes that the project will reinvigorate the college by bringing activity to the front of the building and bustle to its hallways. “I want the place to be alive. We don’t have a lot of large classrooms, there’s not as many people in the building as I’d like to see,” he says. “I want it to be a centre of activity.”

“I want the college to be alive so when students collect in West Hall and march out of the college at convocation, reenacting the history of the college, they say that this is a place where they spent a lot of time; ‘That is where my life at UC happened.’”