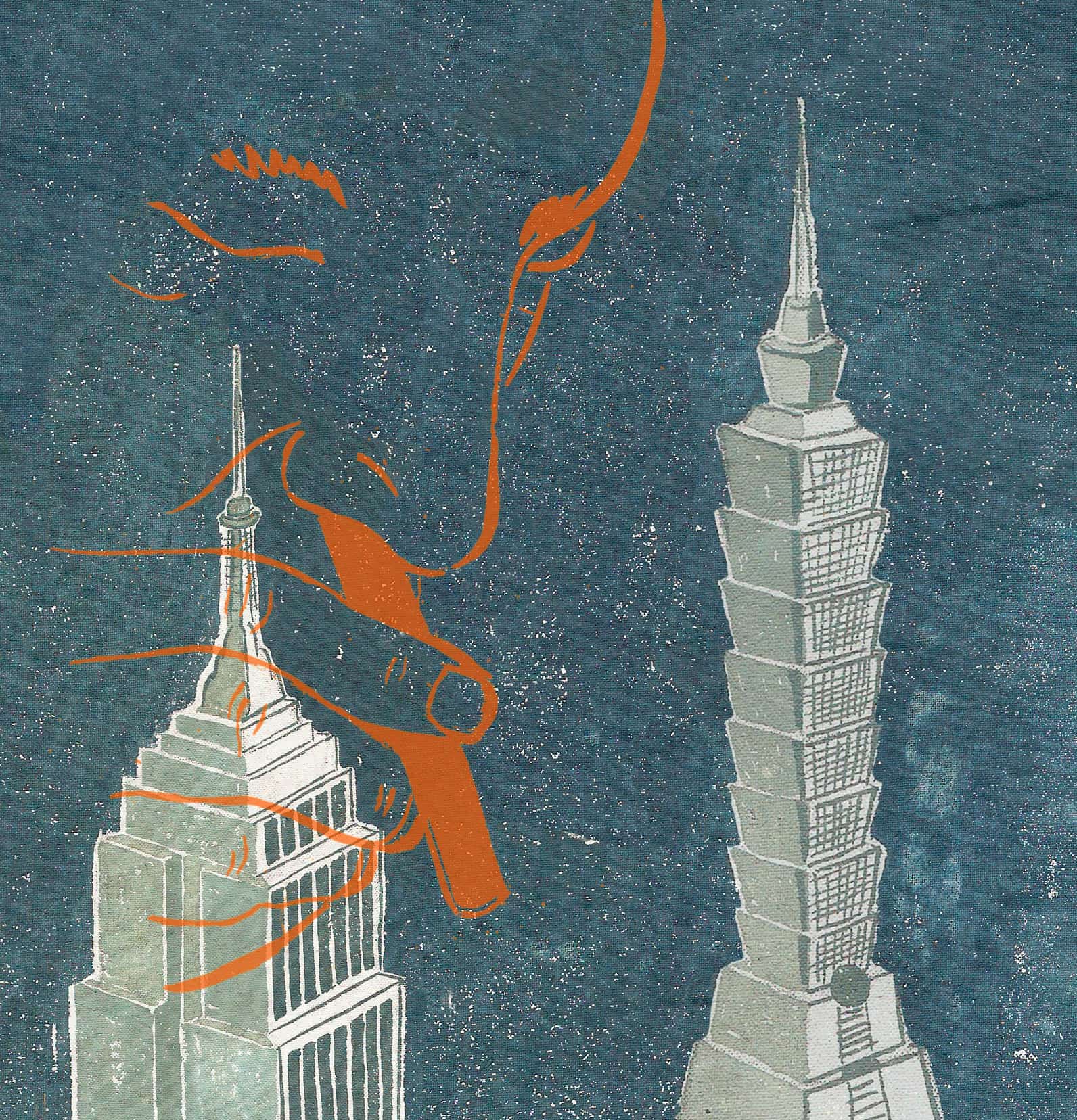

Taipei, Tao Lin’s third novel, features his characteristic stark and minimalist writing style.

Paul, twenty-six, is a writer living amid book launches, restaurants, friends’ apartments, and art galleries while ingesting mushrooms, Ritalin, Adderall, Klonopin, psilocybin, MDMA, and other narcotics — all while harboring a tenuous relationship with his Taiwanese mother.

The generally formless plot of the novel is concerned with the way its characters interact with technology, mostly while under the influence. While on a book tour and drifting in and out of semi-romantic relationships, Paul falls for Erin, a student at the University of Baltimore, spending an entire night “reading all four years of her Facebook wall” and “looking at probably 1,500 of her friends’ photos to find any she might have untagged.” The two begin to hang out, spending an evening together filming themselves answering questions — first sober, and then again while on MDMA — in an attempt to become internet famous. Later in the novel, upon exiting a marriage chapel in Las Vegas, both parties whisper to one another, “We did it” as a sarcastic gesture after a spontaneous elopement; both are cognizant that their fleeting attachment is not enough to sustain a legitimate relationship.

The novel uses brisk, declarative sentences, rife with ironic quotation marks surrounding “seemingly pretentious” phrases that approach incomprehensibility. Lin’s prose style is as self-conscious and stilted as his characters’ worlds, which is mainly where Taipei excels as a work. As a reader, one asks, “Is this what I really sound like? Is this what my friends sound like?”

The novel becomes not only an observational kitsch, but a piece of satiric commentary. The use of free, indirect speech, tunneling through the interior monologue of its main character Paul — who, as it turns out, is a stand-in for the real-life Lin — reveals a character so self-involved, so flagrantly inarticulate that one canfeel genuine, second-hand embarrassment in identifying with his banality before slipping in to a self-deprecating laugh.Taipei‘s characters linger outside of movie theatres, bars, parties, and restaurants, unsure of what to do next. On the surface, this is petty indecisiveness, but it is truly a puzzling and all too common malaise affecting our post-collegiate generation of underemployed and over-educated students: What is it that we’re supposed to do next?