Nawang’s* decision to come to Canada was made in the hope of securing a better future for herself and her children. Before she arrived, however, she endured a decade of moving between India and Nepal as a political refugee.

At 15, she set out on foot from Lhasa in Tibet, trekking for over three weeks through the high passes of the Himalayas with a group of strangers, leaving her family behind to escape into Nepal with the help of a paid agent.

India presented a faith-based calling as the 14th Dalai Lama — Tenzin Gyatso — the spiritual leader of Tibetans — has lived there in exile for most of his life: “Every single day I dreamed of going to India and visiting the Dalai Lama.”

“The first night, I thought I was going to die,” she recalled, referring to her fear of falling through the ice while crossing a semi-frozen river, or of being spotted by floodlights from a soldier’s outposts. In spite of her anxieties, she soon joined the large community of Tibetan refugees straddling India and Nepal.

For many older Tibetans, Nawang’s ordeal is similar to their own tales of displacement. For younger Tibetan-Canadians, her story is reminiscent of their own families’ struggles, inspiring them to become involved with the Tibetan independence movement.

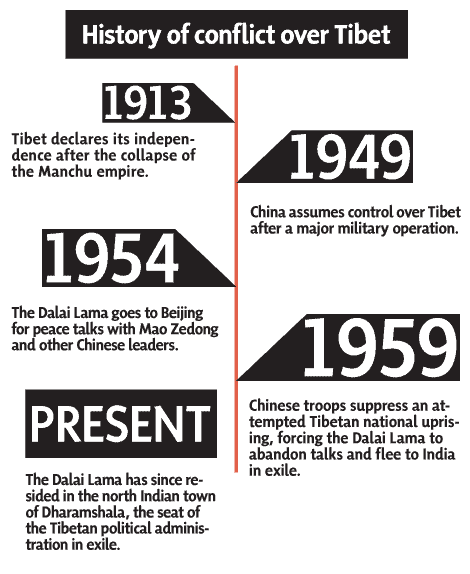

Urgyen Badheytsang, national director of Students for a Free Tibet (SFT) Canada, notes that many Tibetan youth grow up listening to these stories. His grandfather was imprisoned and tortured for taking part in the original Tibetan resistance in 1959; his father was shot in the leg while throwing rocks at Chinese troops during unrest in Tibet in 1989 and jailed, during which time he witnessed a monk get shot in the head. “You already know about everything that’s happening in Tibet, about the repression, and then you hear about your own father and grandfather who suffered at the hands of the Chinese government and it’s not anymore a story, it’s something that’s real, it’s something that’s affected your own relatives.”

A flourishing community

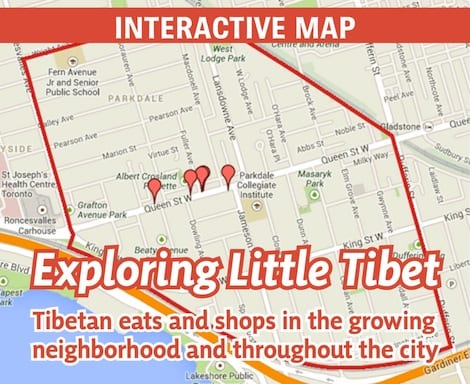

Most Tibetans in Toronto reside in Parkdale and High Park. An array of tiny Tibetan shop windows lie west of Lansdowne Avenue at Queen Street West. A glance into restaurants Tsampa Café and Tibet Kitchen reveal chatty Tibetan families eating momos (dumplings stuffed with beef or chicken and served with a spicy paste made out of red chilies and plenty of garlic).

The Tibetan community in Toronto has more than doubled since 1999. Roughly 5,000 Tibetans now reside in Canada, the majority of whom live in Toronto. Toronto is home to the second largest Tibetan settlement in North America.

Youdon Khangsar, a fifth-year student, co-founded the U of T chapter of SFT. CAROLYN LEVETT/THE VARSITY

Lawyer Connie Nakatsu has represented several Tibetan refugee claimants since 1997. She explains that a growing awareness about refugee claims has put Canada on the map for Tibetans.

Tenzin Tsundue, a fifth-year U of T student, came to Canada with her family in 2007 as part of this wave of Tibetan immigrants. Along with Youdon Khangsar, a fifth-year student, she started the U of T chapter of SFT in her first year.

Khangsar observed, “When I started university here, I found people didn’t even know about Tibet. How can people get involved politically if they haven’t even heard of the country? They have to know about the culture at least, they have to be able to distinguish the Tibetan identity. That’s really important.” In October 2011, Khangsar created the Tibetan Renaissance Association, to promote Tibetan culture in a setting devoid of the political overtones of groups like SFT.

Despite the healthy influx of Tibetans to Toronto, some youth not born in Canada are concerned about the preservation of their language. Tenzin Thabkhae, a second-year engineering student born to Tibetan refugee parents in India, explains that Tibetans face identity issues: “Some Tibetan youth have trouble speaking Tibetan and are therefore uncomfortable to speak with other Tibetans.”

Nakatsu noted: “There was already an issue with [Tibetans] being in India and Nepal, so they were already straddling two cultures as it was, and now what they’re coming to is a third one, so that creates a different set of problems.”

Badheytsang, however, remarked that people should not be alarmed. “I don’t think people are losing their culture. Right now, we have so many youth who might not necessarily have the best grasp of the language but are so involved. They are very passionate about the cause, and might actually know more about the real geopolitical scene than the older generation.”

A compelling sign that the once nascent community is thriving is the Gangjong Choedenling (Tibetan Canadian Cultural Centre, or TCCC), which opened its doors in the west end on October 17, 2007. Tibetan children receive weekend language instruction here in addition to classes on Buddhism and yoga.

The facility includes a large auditorium; a well-stocked library with books on Gandhi, Buddhism, and other eclectic genres; classroom with whiteboards which have the Tibetan alphabet scribbled on them; and, often, the unmistakable fragrance of Tibetan food being prepared. The TCCC has evolved into an indispensable hub for the community — itself an indicator that the community has come a long way since the 1970s, back when Tibetans formed the smallest immigrant group in the country.

Wake-up call

In the lead-up to the Beijing Olympics in August 2008, anti-China demonstrations and protests were held in cities around the world. Images from inside Tibet show Tibetan demonstrators facing off with Chinese authorities. In Ottawa, Badheytsang and four others from SFT chained themselves to the gate of the Chinese Embassy to draw media attention to the Tibet issue: “For me that was the marker. I had decided then that I was ready to throw away everything … to support the Tibetan cause and help our movement go forward. Ever since, everything else has seemed obvious. If you’re willing to go to jail for Tibet then you’re also willing to do a lot of the organizing and behind-the-scenes work.”

Like Badheytsang, Tibetan youth across the country were restless to make the movement their own, with the incidents of 2008 serving as a wake-up call. The demonstrations brought out the activist in students like Tsundue, who quickly became a regional coordinator for SFT.

Tenzin Thabkhae, a second-year engineering student born to Tibetan refugee parents in India. CAROLYN LEVETT/THE VARSITY

Badheytsang notes: “I would say that there’s been a lot more consistency now than before. Before it would have to be a trigger event…Now we have the Lhakar movement.”

“Lhakar,” meaning “White Wednesday,” is a Tibetan self-reliance movement begun after 2008. Every Wednesday, an increasing number of Tibetans both inside and outside of Tibet make a special effort to wear traditional clothes, speak Tibetan, eat Tibetan food, and shop at Tibetan businesses in order to support the Tibetan community.

In Toronto, students have been observing Lhakar for almost two years now. On Wednesdays, it is common for Tibetan students to be seen wearing chupa, traditional Tibetan clothing. On the first Lhakar of September, SFT performed a freeze flash mob in downtown Toronto, urging world leaders at the Russian G20 summit to focus on Tibet.

In February 2009, footage of a monk in Tibet dousing himself in kerosene and setting himself abalze as an extreme form of protest, denouncing China’s treatment of Tibetans, shook the community. Tenzin Wangmo, a Tibetan student intern at the TCCC, notes: “We definitely need more international pressure on the Tibetan issue… More than 100 Tibetans from within Tibet and from outside have self-immolated, yet it seems their voices have been lost.”

MP David Sweet, whose successful motion to make the Dalai Lama an honourary citizen of Canada, adopted unanimously by the House of Commons in 2006, is one of the most vocal critics of China’s human rights record in Tibet on Parliament Hill.

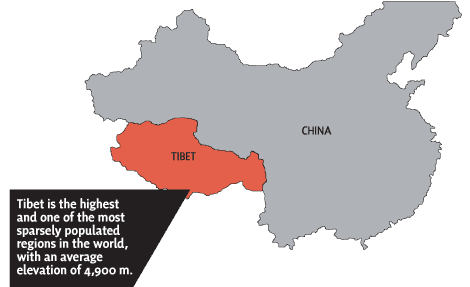

In a speech to the House of Commons on February 14, Sweet said: “Tibetans today live under such oppressive conditions that so threaten their culture, environment, religious freedom and human rights that we have seen, shockingly, over 100 Tibetans lighting themselves on fire in protest. We call on the leaders of China to meet in earnest with the leaders of the Tibetan government in exile to discuss the Dalai Lama’s third way for human rights and democratic, regional, cultural, and environmental autonomy for Tibetans within China.”

Sweet also chairs the Parliamentary Friends of Tibet internship program, geared towards young Tibetan-Canadians. Six Tibetans from across Canada took part in the 2013 program in its fourth year running. Interns worked in the offices of various MPs, learning about the parliamentary system and simultaneously representing Tibetan culture on the Hill. This year, the interns shared a lighter moment with parliamentarians, away from the humdrum of sombre politics, by hosting a lunch reception where they personally cooked momos and made Tibetan butter tea for MPs.

“Interning at Parliament really solidified my belief in governmental and non-governmental organizations. It was so inspiring to see so many people work so hard to help others. At the end of the internship, I felt proud and connected to my community, and was much more inspired to work towards the Tibetan cause and also to help others,” said Wangmo, who interned at MP Peggy Nash’s office as part of the program.

Long road to reconciliation

The Mosaic Institute’s conference, New Beginnings, Young Canadians: Peace Dialogue on China & Tibet, held on September 11 in Toronto, provided an opportunity for youth from both Chinese and Tibetan communities to come together.

Dr. Losang Rabgey, co-founder and executive director of Machik, an organization working to strengthen communities on the Tibetan plateau, urged everyone to put aside disbelief to make connections between the two communities: “When we have only a rights-based discourse as a framework for understanding Tibet and China, it creates a bipolar scenario.” Though rights are an important issue, people also need to encounter one another and explore new opportunities to work together.

Michael Li, a Chinese-Canadian and a recent U of T graduate, found the event very engaging: “In 2008, I was surprised by the scale of the protests. I occasionally found myself getting rather angry in response to them because I did feel that the community I feel that I’m a part of was not being portrayed in a fair light.”

He also acknowledged the importance of dialogue: “I realized that I didn’t know anyone personally from Tibet, I didn’t know what they actually thought. Studying politics, you realize that there are things people say in perspectives that are put forward that don’t actually represent what people think. That is why I attended this session.”

Other Chinese-Canadian students at the event felt that the older Chinese generations’ opinions on Tibet as a mystified, backward hinterland were outdated and misrepresentative. They expressed a desire to understand the genuine grievances of Tibetans. “There are lots of Chinese people who actually sympathize with the Tibet issue,” acknowledges Tsundue, adding that, “First and foremost Tibetans are fighting for the freedom of human rights.”

Nawang, who left her parents and extended family behind in Tibet, is hopeful: “We are always patient. We have hope. Tibetan people are always hoping.”