TIFF has partnered with the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA) for the exhibition, Cronenberg: Transformation, as part of ITS Future Projects and the Cronenberg Project events.

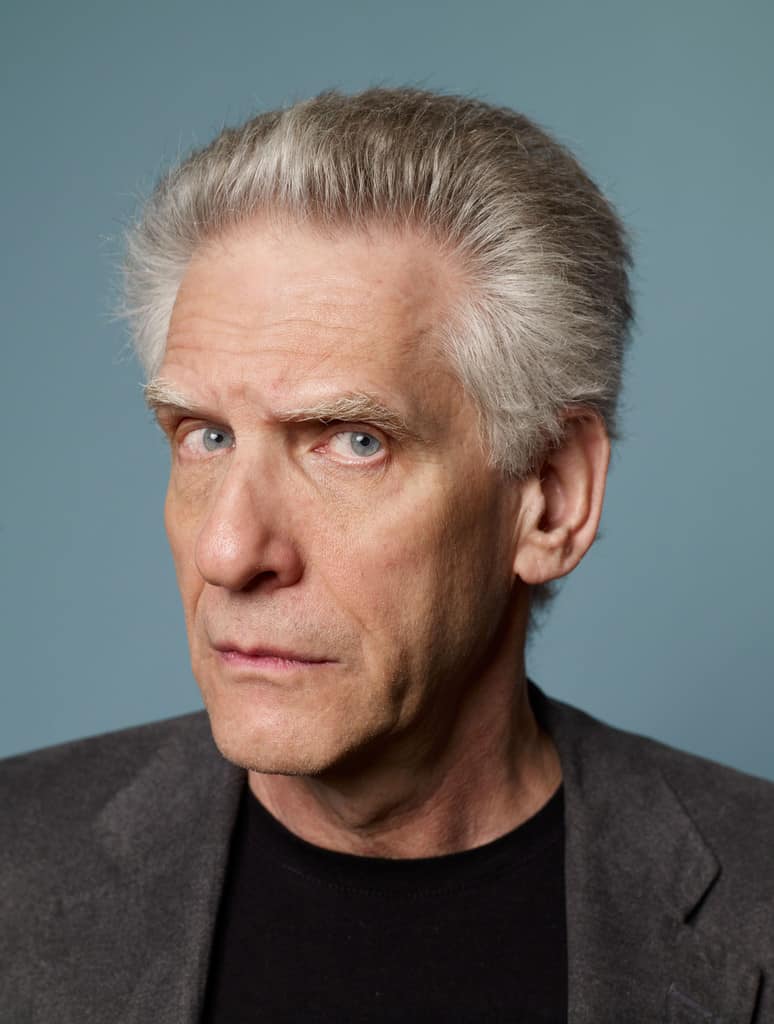

MEDIA PHOTO

Instead of exhibiting works from Cronenberg himself, the exhibit consists of artists whose personal work has been influenced by the director. As the useful and refreshingly concise introduction to the show puts it, the title of the show has two meanings: first, Cronenberg’s preoccupation with transformation, and second, how his work has in turn transformed the work of other artists.

Laurel Woodcock’s piece, “walkthrough,” is a series of adhesive vinyl phrases stuck to the walls throughout the exhibition space, sets the tone nicely with phrases seemingly plucked from generic B-movie screenplays, such as “DEADLY SERIOUS” and, my favourite, “The room goes totally silent. There’s the feeling that something terrible is going to happen.” Standing in a room full of Cronenberg-inspired works, it’s easy to get that delightfully tingling sensation of vague fear after reading that phrase, and it manages to make the standard modern art exhibition space (concrete floors, bare white walls) suddenly feel much more eerie.

The other works more directly hearken to Cronenberg by using film as their main medium. Candice Breitz’s “Treatment” is an eight-minute, dual-screen video; the two films run simultaneously, but their projects are opposite each other in a small room, which makes it difficult to watch both at the same time. While one projection displays a scene from Cronenberg’s early work The Brood (1979), the other shows voice actors recording lines in a sound studio. The audio is the same for both, unifying the separate images. Seeing this piece, I thought of the increasing tendency to consume entertainment on multiple screens, such as browsing the internet on a laptop or tablet while watching television, a practice often actively encouraged by TV channels with the advent of “second screen” features. Can our brains truly handle that kind of divided attention? Is Breitz encouraging us to try to watch both simultaneously, or forcing us to take in one at a time?

Most of the pieces question this influence of entertainment technology, which is unsurprising given how often Cronenberg deals with the ambiguity (and addictiveness) of technology in his films.

While the show can be explored as you please, I happened to view James Coupe’s “Swarm” last, and it felt like a fitting end. A series of monitors, placed high enough so you have to actively look up to see them, show the very room you’re standing in. Instead of showing you, they show people just like you — people who look like average gallery-goers, slowly wandering through the room. The poles holding the monitors up are ringed with what look like cameras just about at eye level, with a bright green light making it seem as though they’re switched on and recording you, so that you might just end up on the monitors later for future viewers to watch. We’re watching the monitors, but they’re watching us right back — this an appropriate message given the pervasiveness of recording in society, from CCTV and the NSA to Vine and Snapchat.

I couldn’t help but find it amusingly apt that one of the pieces, Jeremy Shaw’s, wasn’t working when I visited the exhibition due to a technical problem. As the show so well demonstrates, technology is everywhere — but we’re not very good at controlling it, despite being its creators.

Cronenberg: Transformation is at the MOCCA until December 29.