On May 2, Ontario announced the appointment of a Minimum Wage Advisory Panel to advise on adjustments to Ontario’s minimum wage policy. Ontario is one of three provinces that does not have a formal mechanism for determining minimum wage increases. The panel will examine the current system for increases and recommend a process by which the minimum wage should be determined in the future. The Varsity discussed the panel’s work with panel chair Anil Verma, professor of Human Resource Management at the Rotman School of Management and director of the Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources.

The Varsity: Different jurisdictions consider different factors in determining the minimum wage. Inflation is one such factor. What are the main factors that the panel is considering?

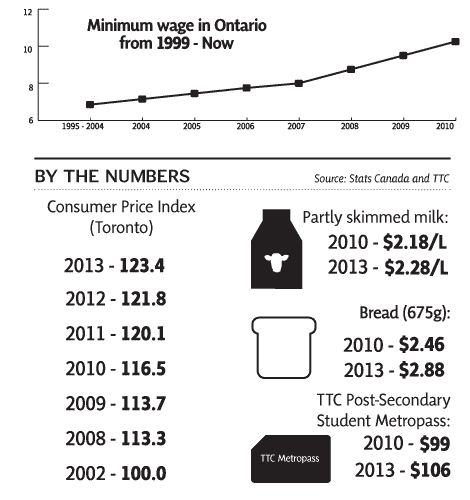

Anil Verma: In most other jurisdictions in Canada, inflation is used as a common basis for revising minimum wages. Our panel’s work will go a little bit beyond. Inflation has been, and will continue to be, a basis. In addition to that, the rate at which the economy is growing may be a consideration, or where other rates are. We are inviting people to make submissions online, and we are getting hundreds of submissions every week. Of course, we are also doing some in-house research where we are looking at the experience of other jurisdictions within Canada and overseas. We are looking at developing a system for Ontario that is transparent, predictable, and fair to workers and employers.

TV: Fifty-two per cent of minimum wage earners are between the ages of 15 and 24. How can Ontario approach the issue of student (particularly, university student) employment?

AV: This is a fairly robust finding in research: the most adversely affected are the young people. What happens here is that minimum wage jobs provide a way for young people to enter the job market. Often, your first job is a minimum wage job. We also know that young people are the most likely to move out of minimum wage. They start there, but they don’t stay there. We have to make sure that minimum wages are not so high that they prevent young people from getting their first job, even as we increase the minimum wage for other groups. There are a lot of people who work in offices and factories, and they are older. Many of these people depend on these jobs for their livelihood and these people would be better served if we had a higher minimum wage. The job of our panel is to balance the two interests of the two groups. We have to let the group do its work, and I don’t want to preempt or second-guess where it might come out.

TV: Many students in university research positions do not receive any compensation for their work. Will the panel address this issue?

AV: This is a tough one, and one that is not central to our mandate. I think we need a more comprehensive look at this. Certainly, the system is being abused by many employers who, instead of paying their employees, are making them work gratis. The principle, in general, is that if you are contributing, you should be paid. This is partly tied up with the issue of education and the transition from school to work. This is a bigger question, and will touch on the work of the panel, but cannot be addressed on the whole by the work of the panel.

TV: It has been three years since a minimum wage increase in Ontario. Does the panel intend to address Ontario’s current ad hoc approach to increases?

AV: One of the reasons why our panel was appointed is to draw attention to the issue of ad hoc-ism. In one sense, the panel has the opportunity to set the bar for future revisions by recommending a basis for revising, the frequency at which it should be revised, and who should do it. What we hope to recommend for the government is an entire package that creates the basis for improvements in minimum wage in the future. Of course, there are a couple of major steps between our recommendations and what would actually be government policy. The minister has to accept our recommendations, and then the government has to create legislation and put it through the legislature.

TV: Some anti-poverty groups in Ontario are calling for $14 an hour minimum wage in Ontario. What would you say to these groups?

AV: As I said before, their interests are also important. But their interests should not dominate the minimum wage decisions of the government. Roughly 20 per cent of the people who work in minimum wage are supporting a household on the minimum wage. 80 per cent of the people are youth or secondary earners within the household. So, this is not to say that the 20 per cent do not deserve consideration — they do. A very robust finding in research is that the effect of increasing minimum wage on poverty is very small. Minimum wage is just one tool to address poverty. There are other tools, like tax rates and income supplements, that address poverty more effectively than minimum wage alone.

TV: One problem with minimum wage research is that one can usually find a study that justifies almost any action. How do you propose that the panel combat this issue?

AV: It is not true that you can show anything. In a number of areas, there is some convergence on what we find about minimum wage. For example, in unemployment effects, it is true that there is some variance, but most studies show that when we increase the minimum wage, there is a slight disemployment effect, but it is only in the range of 1-2 per cent for the population as a whole. They do have a bigger impact on the employability of youth. There is also this general agreement that, when we increase minimum wages, they affect wages that are 10-20 per cent higher than minimum wage. This effect dissipates as we go up the wage scale.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.