Ontario may soon face a critical shortage of nurses, affecting wait room times and the quality of health care, according to the Registered Nurse Association of Ontario (RNAO).

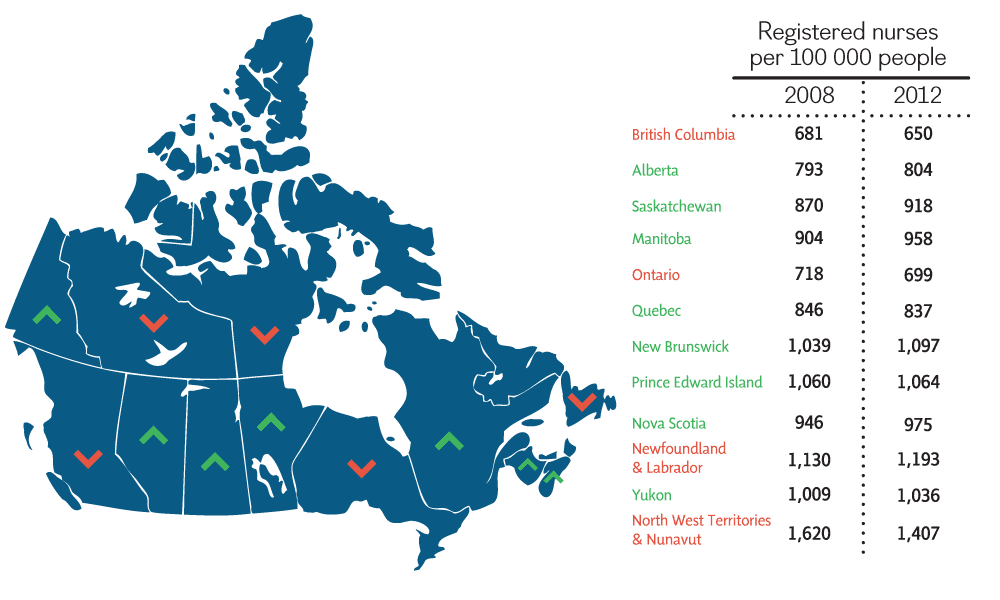

A recent report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) found that, while most of the country has experienced an increase in the number of nurses per 100,000 people, Ontario’s numbers decreased from 718 to 699 between the years 2008 and 2012 — leaving it second-last in the country. British Columbia currently ranks the lowest in nurses per population. Registered nurses are front-line caregivers who have a university degree. While the majority work in hospitals, they can also work in clinics, schools, management, and policy fields.

Dr. Lianne Jeffs, scientific director, nursing health services research unit and associate professor of nursing at the University of Toronto, said the situation must be monitored closely over the next few years in order to ensure the safety of patients in Ontario. She said that while there are some positive aspects of the CIHI report, such as the rising number of nurses working full time hours — 66.6 per cent up from 62.9 — and the number of Ontario nursing graduates remaining in the province at 93.6 per cent, there are still concerns about the decreasing number of registered nurses.

On October 9, the Registered Nurse Association of Ontario (RNAO) quickly released a statement regarding the findings of the CIHI report. Doris Grinspun, CEO of the RNAO, said that the results of the report are nothing new.

“We have consistently over the last three years been warning the minister and the premier that the numbers were dipping,” she said. “But now we are reaching the very grave proportions of shortage.”

The RNAO states that the province will likely need to find at least 9,000 nurses by 2015 in order to keep pace with demand. If numbers are not met, Grinspun said the implications on our health care system could be far-reaching.

“Emergency room departments become fuller and fuller, and the implications will be that people will not have same day access in primary care,” Grinspun said.

A spokesperson for The Ministry of Health responded to the CIHI report via email, saying that: “while the CIHI report noted that Ontario’s Registered Nurse-to-population ratio was the second lower [sic] nationally, RN-to-population ratios are only one indicator of supply and should be considered along other metrics.”

The ministry statement added that the actual ratio and needs of members of the community are hard to measure, and that such changes as advances in health technology, population demographics, and the effectiveness of care delivery models are all important factors.

The statement also adds that while Ontario may have the second lowest registered nurse levels in the country, thanks to government initiatives such as HealthForceOntario, the province’s nurse workforce has increased 5.8 per cent between 2008 and 2012, and outpaced the population growth of 4.4 per cent.

Critics, however, are not entirely convinced that government initiatives are enough to attract more nurses to the province.

Progressive Conservative health critic Christine Elliott. TREVOR KOROLL/THE VARSITY

Christine Elliott, MPP for Whitby-Oshawa and Progressive Conservative health critic, said that the shortage is part of the larger economic problem of the province. “Because our economic situation is so dismal that we really have a debt that’s doubled under the Liberal government and a huge deficit that is really holding us back from making important investments in health care,” said Elliott.

The healthcare system in Ontario is growing at six to seven per cent per year, a rate that is unsustainable, said Elliott. “Within the next 10-15, years health care will consume up to 80 per cent of the provincial budget.” This would severely limit the investment in other areas such as education and infrastructure.

France Gélinas, MPP for Nickel Belt and the NDP health critic, agrees that something has to be done. Speaking with The Varsity on a trip to her constituency, Gélinas said that she hears many complaints about the rural health care system, and not just from patients.

“Work that used to be done mainly by nurses in an environment with lots of oversight now gets transferred to the community, most of the time to a for-profit and most of the time this work is picked up by people who are not nurses,” said Gélinas.

Gélinas said community services generally fall outside the coverage of the Canada Health Act, which lets citizens have free access to hospitals and physician care. She said the CIHI report is a good indicator of the state of the health care system, but added that: “it indicates to us that things have to change; unfortunately things are changing for the worse, not the better.”

“The hospitals are worried; the nurses are worried, and basically everybody who cares about medicare is worried. That includes a lot of physicians who see the changes coming forward and know what that means,” she said, referring to the trend of community care being picked up by private health care workers.

Jeffs said the CIHI report doesn’t include numbers on the number of private workers who may be unregulated. The sectors in which the shortages are occurring are another point of interest for Jeffs are. She said the report raises questions as to whether “we actually having the providers where they need to be to ensure that patients and families in Ontario are getting the best care possible.”

Grinspun said that while the number the RNAO is calling for may not be met, the organization has a responsibility to bring the numbers to light and make sure that the public has knowledge of the situation.

“The research points very clearly to the impact of registered nurses, of hours of patient care, of registered nurses on patient, and population outcomes. At the end of the day, governments need to be accountable for their policies,” said Grinspun.