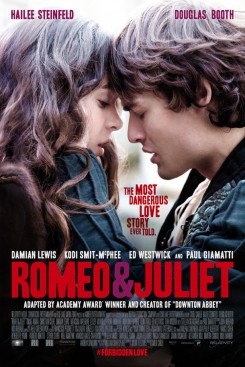

Director Carlo Carlei’s just-released traditional adaptation of Romeo and Juliet is true to the world Shakespeare wrote it in; the last notable adaptation in this style was Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 version. The issue with Carlei’s adaptation is the consistency of the actors. Any production of Romeo and Juliet relies heavily on the performance of its two title characters. Despite a sufficient amount of chemistry between them, neither Douglas Booth (Romeo) nor Hailee Steinfeld (Juliet) were quite up to the challenge.

Romeo’s scenes with Benvolio (Kodi Smit-McPhee) and Mercutio (Christian Cooke) feel a bit artificial, so the audience feels little sympathy when Mercutio is killed by Tybalt (Ed Westwick). In the original screenplay, the audience is supposed to have grown to love Mercutio in the same manner that Romeo loves him, so that when Romeo avenges Mercutio’s death, we don’t see him as guilty for doing so. Of all the Romeo and Juliet adaptations, the most telling performance of this particular scene is Leonardo DiCaprio’s Romeo in Baz Luhrmann’s adaptation. DiCaprio is absolutely heartbreaking, killing Tybalt in a fit of rage brought on by losing his beloved friend. In the 2013 adaptation, Booth does not convey the necessary emotion for the scene and lacks the charisma that DiCaprio displays throughout Luhrmann’s adaptation.

On the other hand, Steinfeld’s Juliet certainly looks the part — young, virginal, and strong — but again, her interactions with the other characters in the movie are not as captivating as they should be. Juliet is an outspoken, headstrong young woman, and Steinfeld doesn’t quite grasp this.

On the other hand, Steinfeld’s Juliet certainly looks the part — young, virginal, and strong — but again, her interactions with the other characters in the movie are not as captivating as they should be. Juliet is an outspoken, headstrong young woman, and Steinfeld doesn’t quite grasp this.

The highlight performances belonged to the supporting cast. Westwick stands out as an excellent Tybalt, convincingly showcasing the character’s bloodthirsty, hotheaded attitude. Paul Giamatti is easily the best Friar Lawrence I have ever seen; his reaction upon finding Juliet dead is beautiful, and is the most emotionally charged moment of the entire film. Smit-McPhee’s Benvolio gave the most surprising performance; although Benvolio’s character had never previously resonated with me, Smit-Mcphee made him the most compelling character in all of his scenes. Benvolio and Friar Lawrence were the only characters that brought me to tears by the end of the film; while this is certainly a testament to the actors’ performances, it also points to a flaw of the film as a whole, since many more characters than just these two should evoke such emotion.

Highlights of the film include the incredible locations — primarily in Veron — stunning costumes, and beautiful cinematography. There are lovely crane and tracking shots that provide a euphoric, wondrous tone. Carlei also beautifully emphasizes motif of hands throughout the film: Romeo and Juliet’s hands come together in a close-up shot when they first meet, are separated from each other just after their wedding night (foreshadowing Romeo’s banishment), and are finally brought back together by Benvolio in the last scene.

If you are a fan of this incredible story, then you should go see this film — if only to look at it from another perspective. If you are a Romeo and Juliet first-timer, I would recommend Zeffirelli’s version — and then Lurhman’s — before this one, as Carlei doesn’t quite grasp the full tone of the play.