How much does it cost the country when high school students drop out of math and science courses? Too much, says a recent “Spotlight on Science Learning” report by Let’s Talk Science, a national charitable organization committed to fostering engagement in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in children and youth.

WILLIAM AHN/THE VARSITY

In Ontario, as in most provinces, math and science courses are optional after Grade 10. As a result, fewer than half of Canadian high school grads actually complete senior-level STEM courses, despite the fact that 70 per cent of top jobs and well over 50 per cent of university and college programs require at least some stem background.

The result? Huge costs, both for students — who may have to go back to school to make up prerequisites or miss out on potential job options and future earnings — and for Canada’s economy, since a decreased interest in these fields leads to a smaller talent pool and the loss of potentially key workers and innovators. Ontario alone “loses $24 billion in economic activity annually because employers can’t find people with the skills they need to innovate and grow,” according to the Let’s Talk Science report.

Part of the problem, according to the report, is that students are often unaware of how many doors they close when they drop out of math and science. If students are not fully aware of the benefits of pursuing STEM courses throughout high school, taking them can seem like a waste of time and effort. Yet many university and college programs, even those in fields like culinary arts, technical theatre, or fitness — at first glance fields unrelated to STEM fields — require Grade 12 math and science courses as prerequisites to admission.

In a 2012 report, the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA) also emphasized the importance of early math and science education in the development of Canada’s future researchers: “Young Canadians lack sufficient knowledge about educational requirements for future careers, as well as a clear understanding of what PCEM [physical sciences, computer science, engineering, mathematics] careers entail… Evidence indicates that there is a disconnection between the educational choices some students make at the secondary level and their post-secondary or career goals.”

In a 2012 report, the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA) also emphasized the importance of early math and science education in the development of Canada’s future researchers: “Young Canadians lack sufficient knowledge about educational requirements for future careers, as well as a clear understanding of what PCEM [physical sciences, computer science, engineering, mathematics] careers entail… Evidence indicates that there is a disconnection between the educational choices some students make at the secondary level and their post-secondary or career goals.”

Dr. Bonnie Schmidt, president of Let’s Talk Science, stresses in the report the importance of science literacy in any of a student’s potential careers, and emphasizes that if educators are to engage children and youth in STEM fields, that engagement needs to start early: “We need to inform our youth of the importance of STEM courses for their future careers, engage them in experiential science learning from an early age, and sustain their interest in science throughout their studies.”

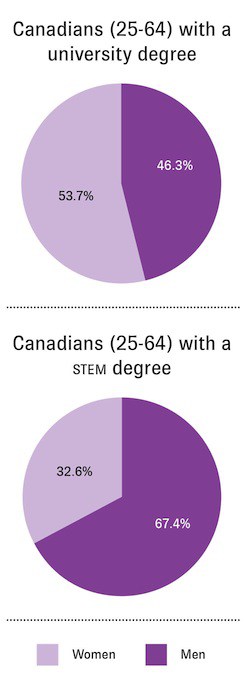

Another contributing difficulty highlighted in the Let’s Talk Science report is the need to engage all segments of Canadian society, including groups that have been traditionally under-represented, such as women and Aboriginals. According to Statistics Canada, women currently account for 53.7 per cent of Canadians between the ages of 25 and 64 with a university degree. However, women represent less than one third (32.6 per cent) of Canadians with a university degree in STEM subjects.

The CCA also noted that women’s representation, not only at the undergraduate and graduate level, but also in research careers and academic positions, varies significantly by discipline. Although women are comparatively well-represented in the humanities, social sciences, and life sciences, they account for only 24 per cent of students enrolled in university programs in computer science, engineering, or mathematics or the physical sciences, and only 14.8 per cent of faculty members in these disciplines.

There is a clear need for more outreach and education, and U of T has recognized this need for some time. A number of programs on campus actively work to combat this lack of interest by getting elementary and high school students involved in exciting, hands-on projects. For instance, U of T works with Let’s Talk Science to mobilize undergraduate, graduate, and faculty volunteers, who run science activities for children and youth at both the St. George and Scarborough campuses.

The Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering has a range of programs in place, like the the Da Vinci Engineering Enrichment Program (DEEP). The DEEP Saturday workshops are classes “designed to introduce students in grades nine to 12 to graduate-level research in science and engineering.” Engineering Outreach also runs Jr. DEEP, aimed at students in grades five to eight, as well as March Break and summer programs. Sample activities include making slime, building model cars, rockets, and roller coasters, or creating musical instruments.

U of T is also leading efforts to address the gender gap. The Jr. DEEP program offers sessions for girls in grades three to eight. On October 19, U of T participated in Go ENG Girl, a province-wide program that invites girls to visit a local university and learn about opportunities for them in engineering from current female engineering students and graduates. Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) at U of T is a co-ed student organization that sends volunteers to high schools across the GTA to encourage and inspire students to pursue science and engineering at the postsecondary level.

A great deal of work is being done to address the lack of interest and lack of knowledge about stem subjects that both the CCA and Let’s Talk Science have identified. Nevertheless, it’s important to keep in mind that Canada’s potential for innovative excellence in these fields depends on students’ talent —and if they aren’t interested, everyone loses.