In a landmark lecture delivered in post-war Paris, the prominent French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre proclaimed: “In life, man commits himself and draws his own portrait, outside of which there is nothing.” While I am not going to discuss the details of French existentialism, I could not help but select this particular line to characterize the theme of the undergraduate existential crisis.

ALLAN TURTON/THE VARSITY

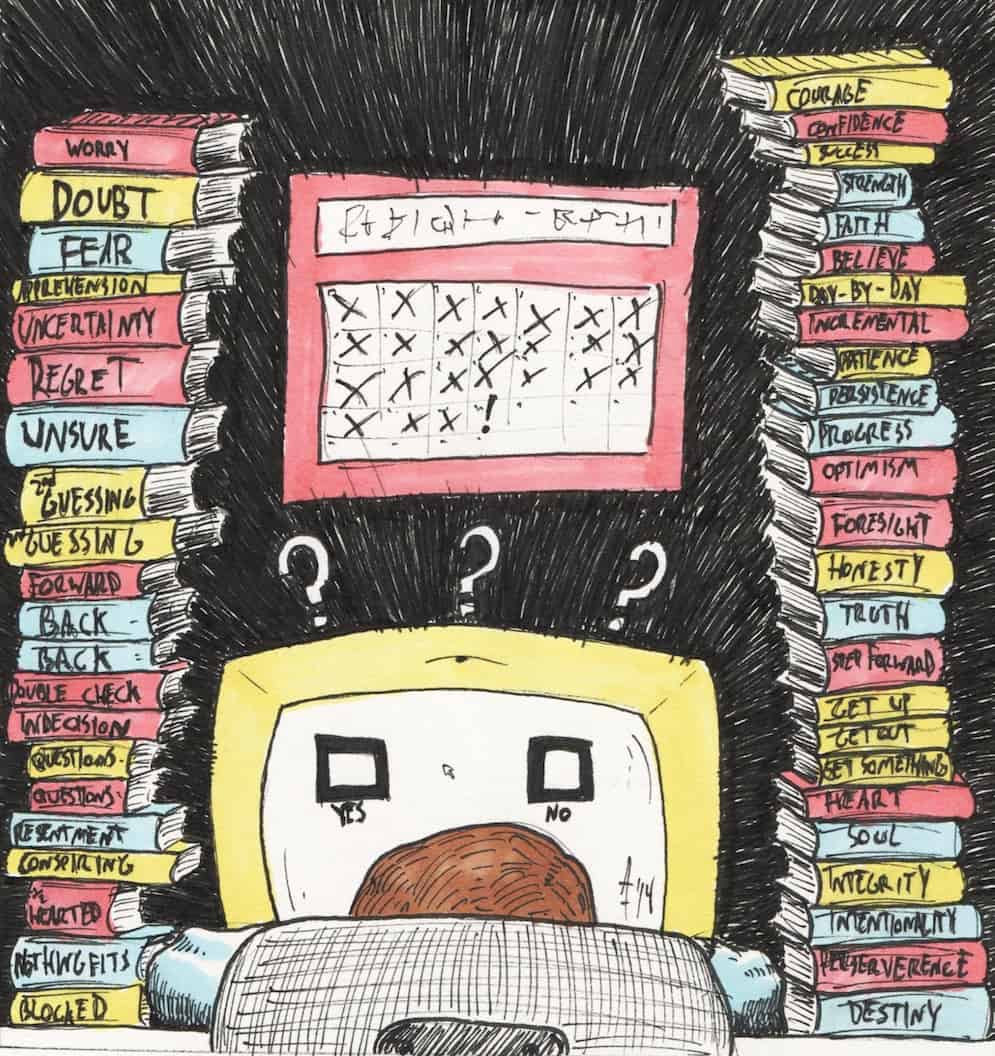

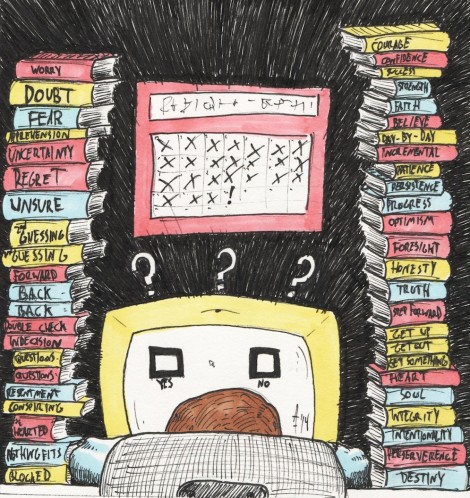

As an undergraduate student, I find that there is a peculiar emotional state associated with being at a university like ours — a lingering yet uncanny feeling hovering in our collective consciousness. As we go about our daily lives on campus — attempting to register the overwhelming number of faces we come across, and walking in the shadows of the alumni that have come before us over the last two centuries — there is a seemingly inevitable feeling of deindividualization: “Am I just another number?” “What is the purpose of all of this?”

Let’s look at some recent statistics: Student enrollment figures provided by the University of Toronto report that during the fall of 2013, 55,345 undergraduates were enrolled in courses across all three campuses. Upon reading such a startling figure, one has to ask: “How can I stand out?”

There is a fundamental need for recognition, a struggle for individual identity, at U of T. The very benefits of the existential crisis I speak of lie therein. More often than not, such a crisis is perceived to be a negative, bleak, or even hopeless period in one’s life. I see it as a driver of achievement, a sort of epiphany, a call to create change.

One may dismiss the claim for its overt optimism, but it is only in such unscathed optimism that one creates substantive change. Our constant search for meaning, anchorage, and purpose within the larger U of T community can empower us to compete, challenge ourselves, and meticulously carve out our paths. Having said that, I wish to transform the conventional schema surrounding an existential crisis in this particular context.

Essentially, inquiry paves the way for the quest for meaning. Finding out where one’s passion lies could be one of the most challenging feats, especially given the plethora of programs, majors, minors, and specialists spanning the academic spectrum in its entirety. Hence the often-echoed phrase: “What am I doing with my life?”

Ironically, I think this is not only a crucial question everyone should dare to ask, but also one of the first attempts at seeking one’s true potential in our academic milieu. Decision-making begins in introspection. Though I do not categorize myself as an existentialist, I find Sartre’s philosophy of choice quite motivational in its endless struggle for meaning through action, change, and choice. Largely, we — as students of a large university — should not let desperation seep in during such a crisis, but rather embrace it as a reflective process.

If we begin perceiving the existential crisis through an optimistic lens, we suddenly find ourselves discovering new interests, confirming current ideas, or even reconsidering a course or career path. In today’s world, crises of self seem to be on the rise, and there is no doubt that it is also prevalent in our student community. Ultimately, a paradigm shift in the way such deeply personal periods are perceived and dealt with by the public will impact their outcomes on individuals. After all, we all need to reflect on our portraits every once in a while.

Omar Bitar is a fourth-year student at University College studying neuroscience, sociology, and biology.