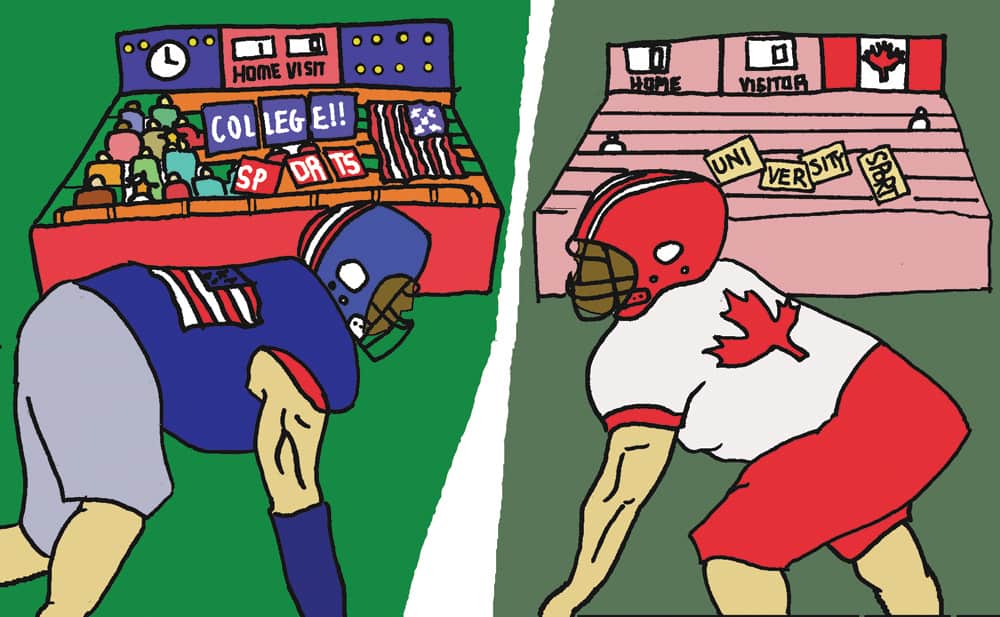

The differences between student athletes north and south of the border couldn’t be more apparent.

Student athletes do not receive athletic scholarships in Ontario surpassing $4,000. Recently, to help mitigate the increased exodus of Canadian athletes to the U.S. on scholarship, the Canada First program was created.

The Canada First scholarship helps some 1,800 athletes across Canada. However, it only provides $900–$1,500 a month, as opposed to tuition costs and bursaries that US institutions can provide for student athletes.

In the US, the experiences of student athletes vary. Although full athletic scholarships are available in the US, and equally distributed amongst men and women, they are not equally distributed amongst sports.

Take for example baseball versus football: baseball division-I programs have a limit of 11.7 scholarships for 32 rosters spots, while division-I Football Bowl Subdivision football programs are limited to 85 scholarships for a 117 roster spots. Many baseball players are offered partial scholarships and seek alternate paths, like entering professional draft out of high school, or taking football scholarships, which are easier to come by.

Most major colleges in the US choose to invest in the money-making programs like football. A recent study conducted by Business Insider found that based on fair market value (using proportions of salaries to revenue based on the NFL Collective Bargaining Agreement) college players at the University of Texas should be paid $578,000 a year on average. Colleges treat their athletic departments like a business allocating resources to higher performing departments, yet they do not pay their athletes.

At the beginning of the 2013 National College Athletic Association football season, several players step onto the field with APA emblazoned on their jerseys. This was a statement meant to address the growing sentiment that NCAA players should be paid as employees for playing sports. After all, the stadiums they played in were full of paying customers, and their names and likenesses are used on jerseys — that sell for $85 like Heisman winner Johnny Manziel — and in video games, such as the long–running NCAA football franchise.

The reportedly 10 per cent of college programs that are only making profit have come into question because of Western Kentucky, alledgedly using creative accounting practices to hide millions in profit. Cases like this have created skepticism amongst NCAA athletes and have spurred them to redress their exploitation.

This stands in stark contrast to Canadian student athletes. Jerseys with their names are not sold for massive profits, Canadian Interuniversity Sport football does not have a video game, and, in general, the programs aren’t as much unprofitable as underfunded. Not to mention, attendance and gate receipts for sports varies at most universities — all U of T sports games are free with your student card.

In order to keep their programs afloat, Canadian student-athletes volunteer their time with fundraisers, or, in the case of student-athletes at U of T, are buying clothes from Adidas with a portion going back to fund their own programs due to the athletic department’s limited resources.

The resources at U of T are limited for athletes, whereas some programs in the US make upwards of a $100 million of profit per year. Regardless, a similarity that one can find between student-athletes across North America is that, based on their circumstances, they are faced with unique challenges in order to play the sports that they love.