Video games occasionally receive a bad rep in the mainstream media for being violent, but research is showing that they can also have surprising benefits. Student researcher Natasha Ouslis is a second year psychology specialist who, working in the Research Opportunity Program (ROP) under Dr. Ian Spence, is carrying out research on 3D visualization and memory. During the course of her research, she has discovered some surprising side effects of video games.

MARI ZHOU/THE VARSITY

The Varsity: Can you describe your research?

Natasha Ouslis: I’m in a psychology research lab, and we work on working memory. We do a lot of computer programs that we give to participants, so we use people and we look at their behaviour, accuracy, and reaction time. Not so much lab benches and gloves and white coats, but just a lot of getting people to come in and seeing how they do on the different tasks that we’ve done. So we have a few different things that we ask them to do, and different inputs that we have for them.

We do a lot of trying to understand: if someone does well at one thing, will they do well at something else? Are these two tasks going to be related? And will that help us understand how people are good at science and technology fields? Usually people need spatial ability, so that kind of working memory, as opposed to verbal working memory. Your verbal working memory would be if you just saw a phone number in the phone book and you’re walking to the phone, forget and you have to go back and look again.

TV: What sort of tasks do you ask the participants of your lab to do to test these things?

NO: We have wheel spikes, and they’ve all got these different images. One of them will flash as a filled-in spot… This flash happens for only 30 milliseconds, so it’s really, really quick. We tell them that at first that they probably aren’t going to notice it at all. Eventually, you get better and better at deploying your attention to that one thing and ignoring all of the other distractors, which is part of the spokes of the wheel.

And that is something that we’ve found is linked to a lot of practice in video games. That is the exact same kind of attention and looking through distractors to find that one target that we do in our task, in a little bit of a different capacity.

The other task that we do is storing locations in memory…they have to remember this whole random collection. It’s not in an organized pattern of locations, and they’ll have to keep that in their memory while everything is wiped from the screen.

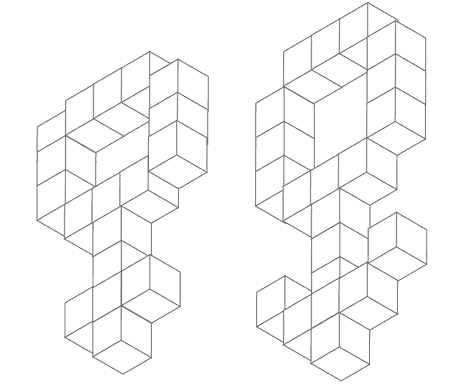

And there’s a third task. Two Tetris-like blocks that are 3D, and they have to rotate one to see if it’s identical to the other one or a mirror image. And this one takes a lot longer, so they get about eight seconds to think about it; it can be quite a difficult task.

And all of these things we’ve found are related to excellence in fields like engineering, science, technology, and math. So we’ve done some training studies in this lab to see if people that do well in that can get better at those tasks by playing these action video games where they’re super quickly looking all over on the screen — they’re clicking and doing all this stuff — is [that] related to these increases in these skills of the tasks that we look at.

TV: Where do you think this research is going to go?

NO: What we’re finding with these training studies and where it’s going is that basically, this is the reason that we might not have people [like women] inclined to go into these STEM fields. The opportunities are there, there are so many women in university, there are so many women in high school science courses, there are so many women who are good at the computation and organized. And we still see a huge difference in some of those fields.

And this is something that we can talk about. Look at what happens with girls when they’re young, and what kind of toys they play with, and whether they’re inclined to play these kinds of video games. Which are good for attention, but are also really violent… They’re just not attracted to that. But the games that they are playing don’t develop these kinds of skills.

So I think that it would be really great to prove that this isn’t some inherent difference, and that this is a capacity that you can overcome. Especially this specific kind of memory that girls have shown that they catch up just to guys, even with only about ten hours of video game playing. It’s really quick, and it’s really promising, I think.

TV: So this research says some very positive things about video games, doesn’t it?

NO: It does, and it’s hard to reconcile that with what we see in the media. But what we’d love to do, and what a lot of people in the lab talk about, is developing video games that keep these elements that are good, and just take out the violence element. But try to find a way to keep all these other things, make them appealing to a larger audience…

If everything that’s good at teaching you these skills of working memory and attention is rated m and is not showing the right kind of values from a storyline perspective, then parents are not going to be inclined to do that even if we say, “This is really good for you. You learn all these things, and it’s going to be really great!” But you have to get through the fact that there’s blood and gore and all this stuff is happening on the screen, and that’s not something that you’d condone for your children.

So it’s very mixed. There’s a lot that you’d have to get through, and there [are] marketing concerns in what’s more interesting to people and what are people willing to buy.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity. Read an extended version online at thevarsity.ca