Around this time last year, several of the divisions held referenda in hopes of diverting their fees away from the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU). Such referenda would have essentially spelled separation from the centralized union for Trinity College, Victoria College, and the Engineering Society (EngSoc). The UTSU refused to recognize these referenda at the end of the year, prompting further protestation from the disgruntled divisions, who proclaimed the rejection of the referenda illegitimate.

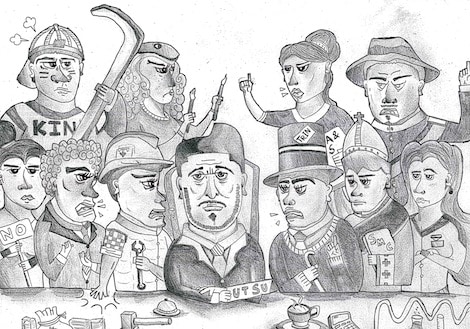

ARNOLD YUNG/THE VARSITY

To avoid a series of messy lawsuits between divisions and the union, U of T’s administration intervened and convened a series of meetings, the Student Societies Summit, which took place this year with a view to coaxing the various factions towards an amicable resolution. After a year’s worth of unproductive discussions, the UTSU and University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU) pulled out of the summit before final meetings had taken place. The prudence of this move remains questionable, as the summit prepares to deliver its final report to U of T’s administration with suggestions for UTSU reform.

As an incentive for all sides to reach a compromise, the administration put the construction of the new student commons on hold. The result is another year spent without construction commencing and little to show from the summit.

The central argument in defense of the summit is that it has hopefully provided U of T’s administration with the evidence it needs to take substantive action over the summer. However, if U of T did not already have all the information it needed from the 12 years of confrontation since the union joined the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), and the coverage of the referenda in The Varsity, then a series of discussions are unlikely to leave them better informed.

The positions of the dissenting divisions and the incumbent slate, U of T Voice, which will control the UTSU executive committee next year — with the exception of Pierre Harfouche, the newly elected VP university affairs, who has been an advocate for fee diversion in the past — are irreconcilable. If the administration does not take unilateral action to change the form of student government at U of T, then its unlikely that the summit will have done anything to prevent litigation.

So what should U of T’s administration do? Actually allowing fee diversion would be a foolish response and would not do anything to address the underlying issues that caused this tension in the first place. The disgruntled divisions are angry at the conduct of the CFS affiliated UTSU, and have come to feel that reform is impossible. Solving the union’s real problems will remove their desire to leave.

A better solution therefore would be wholesale UTSU reform. The main problem this presents is the challenge of cleaning up an organization whose primary fault is not in the letters of its policies but in the culture of those associated with it. This is not something that can be easily fixed with new policy.

The best course of action would be to take power out of the hands of the CFS and to put it into the hands of individual colleges, while maintaining a campus wide presence. I propose a federal structure, in which a committee of elected college and faculty representatives constitutes the UTSU executive, with those representatives electing a president internally. Having each representative be primarily responsible to his or her constituency, assured more effective divisional representation at the executive level.

Of course, there are a number of existing UTSU constitutional roadblocks, which would make such reform difficult. The easiest way for provost Cheryl Regehr to go about establishing a federalist style students’ union is by stripping the UTSU of its levy and the levies directed through it.

Stripping the UTSU of its funding will also make retaliation more difficult for CFS-affiliated members and other supporters of the status quo. Lacking student levies, the UTSU membership will no longer be able to pay fees to the CFS. Without the assurance of steady funding and student programming, how can the CFS maintain an interest in propping up the current UTSU, especially when the costs of litigation are sure to be high? So high, in fact, that the CFS could not reasonably assume the financial burden when a future of continued fee collection from U of T students is uncertain.

While the summit was wasteful, the current UTSU’s decision to walk out on the process gives U of T’s administration a unique opportunity to fix student government at U of T — one that ought to be acted upon.

Jeffrey Schulman is a first-year student at Trinity College studying classics.