The Digital Innovation Hub in the Toronto Reference Library is exactly where you would expect something as futuristic-sounding as 3D-printing to find its home.

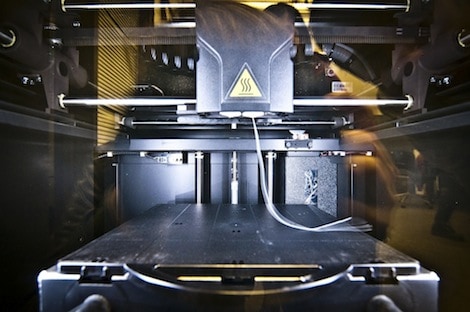

3D printers range from $600 to over $1 million. BERNARDA GOSPIC/THE VARSITY

This small room in the massive reference library is home to about a dozen computers, two 3D printers (or “MakerBots”) and an extremely tech-savvy staff. In between helping people with virtual models destined for the printer, Innovation Hub staff assemble and attempt to fly a small, four-winged airplane while they wait for Derek Quenneville, the “3D-Printing Evangelist.”

Quenneville is the current innovator-in-residence at the Digital Innovation Hub. He’s the production manager at 3D Phacktory, a 3D-printing studio in Toronto, and runs Toronto 3D-printer meet-ups for those interested in this extraordinarily niche area of design.

While many of us may dream of printing our heart’s desires in a perfect, three-dimensional copy, it’s not as easy as it sounds. Speaking to a small group of 3D-printing novices at the Innovation Hub, Quenneville explains that 3D-printing requires quite a bit of technical knowledge. Familiarity with 3D-modelling softwares, like Open SCAD, is absolutely necessary. Those involved with the mechanical aspect of 3D printing at Quenneville’s own company are mostly engineers.

“3D printing as a commercial thing was basically invented last year,” says Quenneville, who doesn’t expect that 3D printers will become household items anytime soon. There’s just no need, since “nobody’s using their 3D printers 24 hours a day. Maybe they can throw one in next to the laundry room in an apartment building,” he adds with a laugh. For now, while the cheapest 3D printers cost about $600 and industrial printers can soar above $1 million, independent companies like Quenneville’s will likely continue to exclusively handle people’s 3D-printing needs. These needs are surprisingly diverse, despite the cost and complexity of the process.

The 3D Phacktory clientele’s projects range from the purely artistic to the very practical. For example, it printed the genie lamps for this year’s Mirvish production of Aladdin, and has produced science-fiction figurines for films, board game parts and pieces, and prototypes of products entrepreneurs intend to bring to market.

Quenneville is especially enthusiastic about Cosmo Wenman, an artist who scans and prints life-sized, 3D prints of famous works of art, including the Venus de Milo. He then uploads his scans online to the popular design-sharing site Thingiverse, where anyone can download and 3D-print them. If it sounds like plagiarism, then you’re not using your imagination.

“You can download it, remix it, and print it,” says Quenneville. This means the Venus de Milo can be downloaded and altered in any way through 3D-modelling software, by anyone with enough technical know-how. Proportions, facial features, and colour can all be changed before the final product is printed, resulting in an infinite number of possible Venus de Milo “remixes.”

Of course, as with any technology, 3D-printing has limitations. The nature of commercial printers, like those at the library, means that everything has to be printed in plastic. The kinds of plastic that can be used varies, but they are generally not dishwasher-safe. This means that printing plates or cutlery is out of question. As well, since 3D prints are filled with a plastic latticework of adjustable density, “bacteria can get in between the layers, and you can never be fully sure it’s gone when you clean it out,” according to Quenneville.

3D scanning comes with its own set of limitations. Anything too shiny is tough to scan, and Quenneville explains that when people want to have themselves 3D-printed, they have to cover their hair with corn starch — otherwise, it will be too shiny for the laser to properly scan.

In addition to the technological limitations, there are also social ones. At the Digital Innovation Hub, for example, clients are prohibited from printing weapons, weapon parts, or obscenities.

By and large however, the possibilities of 3D printing greatly outweigh the limitations. Even U of T has found uses for this technology. At the Digital Fabrication Lab in the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, students have access to multiple 3D printers and scanners.

The applications in architecture are substantial. For Quenneville, printing small-scale models of proposed buildings for urban developers and architects is “a very common request,” so it seems logical to give architecture students some level of competence in 3D printing and scanning.

The possible applications of 3D printers are just beginning to be explored, and with people like Derek Quenneville paving the way, U of T students may be well on their way to playing an important role in this burgeoning industry.