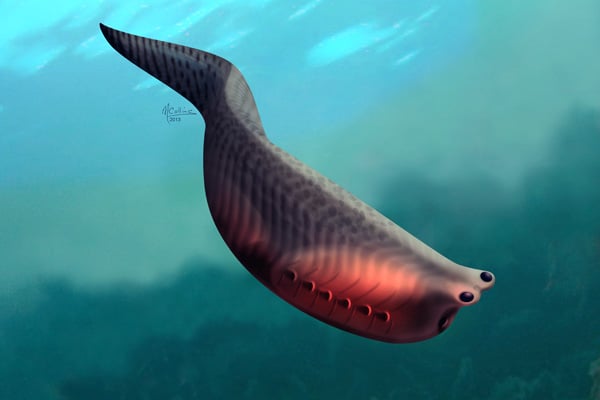

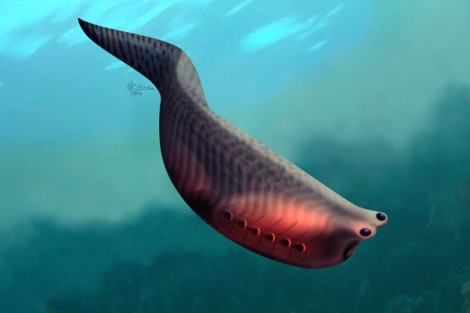

Fossils of the 505-million-year-old fish recently found by Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, the award-winning curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) and associate professor at U of T, answer many questions about the evolution of jaws in vertebrates.

Caron and a ROM-led team discovered a new fossil site in 2012, near Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia. The site is rich in specimens from the Cambrian period — an extraordinary time when the diversity of creatures increased exponentially. During their 2012 expedition, Caron and his team found fossils of 55 species in two weeks, and a quarter of these are new to science. They also collected over 40 specimens of the previously elusive fish Metaspriggina. The team has been studying the fossils fervently and the results have been published in the scientific journal Nature.

Caron recalls, “I still remember vividly when I first recognized the distinctive shape of the W-shaped muscles tissues in the field and I was very excited — I thought this was a very promising find!” These bands of muscle facilitated swimming in Metaspriggina, similar to fish today. He adds, however, “The true significance of this fish became apparent only when the material was brought back to the ROM and after carefully preparing the fossils by removing sediment-coated parts of the body.”

“Perhaps the most remarkable structure preserved in this fish is a series of cartilaginous pharyngeal bars just behind the mouth,” says Caron. “The first pair of these bars will eventually become part of the vertebrate jaws much latter in evolution.”

It had been hypothesized that such a creature had existed many millions of years ago, but no fossil had yet shown solid proof. Caron says, “Metaspriggina provides a wealth of new evidence regarding some of the first steps in the evolution of vertebrates.”

Two fragmented fossils of Metaspriggina had been found previously at a similar nearby site at the famous Burgess Shale in Yoho National Park. “The two specimens were all what we knew about the early fossil record of fish during the Cambrian period in all the Americas,” says Caron.

Caron and his team headed back to the fossil-rich site earlier in July for 10 weeks. “We expect to find new specimens of this fish and perhaps many new species of animals that lived in similar marine environments at the time of the Cambrian period,” he says. There are still many questions left unanswered, says Caron. For instance, while the Marble Canyon specimens were thumb-sized, he hopes to determine how large the creatures actually grew, in addition to determining whether or not they had fins, among other things.

The ROM hopes to display these amazing finds in a future permanent gallery, The Dawn of Life. Caron says the exhibit, for which funds are still being raised, will feature other never-before-seen specimens including those from Canadian UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

He adds, “This fish will be part of an amazing exhibit telling the story of life, from its origins, more than 3.5 billion years ago to the age of the first dinosaurs.”

With files from CBC and the National Post.