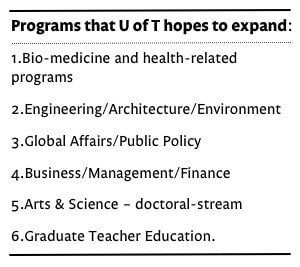

The University of Toronto, along with 43 other universities and colleges in the province, has struck a deal in which post-secondary institutions must identify their strengths and then select five or six key programs for expansion.

As part of the Strategic Mandate Agreement (SMA), U of T will receive funding for 428 new master’s students and 152 PhD students over the next three years.

The SMAs are aimed at ending program duplication and allowing universities to specialize in certain areas, a process known as differentiation. According to a Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities policy report, “The government’s policy of differentiation sets the foundation for broader postsecondary system transformation by publicly articulating government expectations and aligning the mandates of Ontario’s colleges and universities with government priorities.”

Yolen Bollo-Kamara, president of the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), criticized the SMA for failing to address the problem of provincial education underfunding. “This model does not include new funding for institutions and does nothing to address the root causes of the problems universities are facing,” she said, adding: “The model disadvantages students who are unable to attend an institution outside of their community, by rewarding universities for reducing funding for some departments or slashing them altogether, endangering the diversity and quality of program and course offerings.”

“The under-funding of the system has been a long-standing issue for the university, ” said Althea Blackburn-Evans, director of news and media relations at U of T.

Blackburn-Evans emphasized that the SMA would not result in the deterioration of undergraduate education. “The university remains committed to further strengthening our undergraduate education on all three campuses, through a range of initiatives, [including] small-group learning, entrepreneurship opportunities, and experiential learning,” she said.

Pierre Harfouche, UTSU vice president, university affairs, said that the SMA was a good short-term solution, provided that the university has the opportunity to switch the programs that it expands once the initially expanded programs have had the chance to flourish.

According to the university, one of the key components of the SMA process was the allocation of additional graduate spaces, and no further funding decisions were included as part of the SMA process. “Changes to the funding formula and the long-term sustainability of the system were not addressed as part of this exercise,” said Blackburn-Evans.

Abdullah Shihipar, president of the Arts and Science Students’ Union (ASSU), said he supports specialization and differentiation at the university, but has concerns over how specific the funding is.

“The Ontario government determines funding so it’s not necessarily everything a university specializes in, but rather, what the Ontario government determines to be of value that gets funded,” Shihipar said.

Shihipar pointed to a number of unique U of T programs, including Caribbean Studies and East Asian Studies, that he said should receive more funding. “We have these niche programs that, under true specialization, would get extra funding because they’re located at U of T… [N]owhere else in Ontario necessarily covers them,” he said.

Both Harfouche and Shihipar noted that the SMA is driven by U of T’s desire to foster entrepreneurship and global research, but worry that funding for other programs may be compromised as a result. Harfouche expressed concern that programs with high enrollment — such as the humanities — were not proposed for expansion. “It’s important while these other programs grow, humanities and social sciences don’t stagnate or lose funding,” he said.

Among the strengths identified in the SMA are U of T’s undergraduate and graduate education, research and entrepreneurship, and student enrollment demographics. The SMA includes both institutional and system-wide metrics that are the same across all post-secondary institutions in Ontario. The institutional metrics indicate those areas that a university or college designates as top priorities, as well as a number of strategies in place to maintain them.

One of the university’s top priorities is fostering student innovation, specifically regarding the number of inventions by students and faculty on campus, the number of start-ups created, and the number of students receiving early exposure to entrepreneurship. Harfouche expressed hope that the university’s desire to support entrepreneurship would lead to discussions on U of T’s policies on intellectual property. “If they’re going to push entrepreneurship on campus, they’re going to have to start opening up those discussions to students,” Harfouche said.

According to the SMA, the university’s focus areas regarding experiential learning are the number of students who have research opportunity or co-op experiences, as well as technology-assisted learning with the number of online credit courses and programs.

The only institutional metric that U of T included on student population was the number of international students enrolled. In contrast, the University of Waterloo included metrics on the average OSAP debt of graduating students and the average waiting time for a student to access counselling.

The SMA is in place from 2014–2017.