Students looking to save money at the start of the term will continue to be disappointed by soaring textbook prices. For students taking a full course load, the burden can sometimes make or break their financial stability, with textbook costs routinely exceeding $500.

Though the cost of textbooks at university is now considered a fact of student life, some sources suggest that there is an underlying cause explaining the rapid increase of textbook prices.

According to The Economist, textbooks are immune to demand-based incentives to lower costs. Since instructors set class readings without budgetary restrictions, there is no incentive to choose a less expensive text than that which they see as most comprehensive. It is also common for professors to assign their own written works for their class readings.

According to statistics from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, textbook prices have increased at a rate three times that of inflation since 1970. Meanwhile, students continue to feel the weight of textbooks on their backs and in their bank accounts.

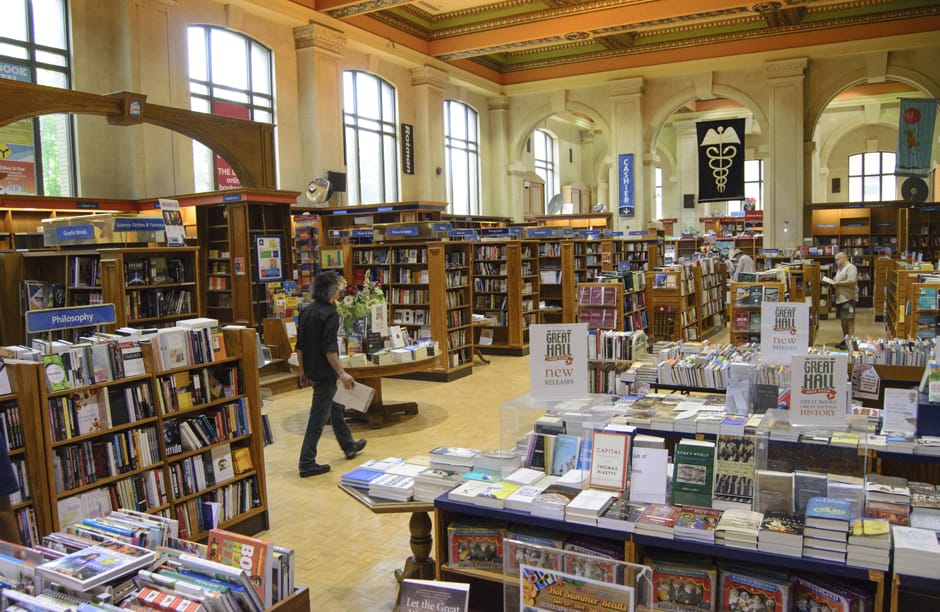

Kate* and Ada*, first-year nursing students at the University of Toronto, bought their first set of nursing textbooks last Thursday, and were unpleasantly surprised by the $400 bill at the bookstore.

“[T]hat’s not even including our medical materials,” Kate said. The additional cost of equipment leaves many students reaching deep into their pockets. The U of T Bookstore sells stethoscopes for between $17 and $35, scrubs are priced at $25, and tuition for nursing students is $8,100.

For the two nursing students, the expense of textbooks creates a significant dent in their student budgets.

“They don’t talk about how much books cost,” said Ada of entering the highly competitive program, adding: “[S]tudent loans won’t give you extra for your textbooks.”

Kate, who does not receive student loans, is concerned that her limited line of credit will not be enough to cover the compounding costs of her program, and working part-time might be the only viable option.

“You have to do so well in this program, but you have to get a job at the same time. How do you balance it [all]?” she added.

Many attempt to alleviate the burden by using unconventional avenues to acquire course materials.

One such service is Bookwiz, an online platform for inter-student textbook exchange founded and developed by U of T computer science student Leila Chan-Currie. According to Chan-Currie, her website acts as a facilitator to better connect students who are already engaging in an informal textbook exchange market.

“Bookwiz is part of a larger movement towards a localized, decentralized sharing economy facilitated by the internet,” said Chan-Currie.

“It reduces demand on traditional bookstores the same way apps like Lyft are replacing taxis and Airbnb is replacing hotels,” she added.

Aidan Douglas, a third-year student, has long navigated the online exchange market, using Toronto University Student’s Book Exchange (TUSBE) to find deals.

“I can usually find my textbooks being sold by other students at a 50-60% lower price than that being offered by the U of T Bookstore,” said Douglas.

Exchanging between students, however, is not always convenient, especially when the prospective sellers do not have the correct edition.

“Last year, I unknowingly bought an international edition of the Astronomy textbook I was seeking, which I later found out was illegal to sell in Canada,” she said.

According to Althea Blackburn-Evans, U of T director of media relations, the university assists struggling students by providing a cost-effective textbook rental program, and maintaining a rich physical and electronic library which is available to all students.

“The university recognizes the cost benefits of alternatives to purchasing new textbooks for students,” Douglas said.

Douglas agreed that the ability to rent textbooks is a great way to access brand-new materials reliably without the high costs, but noted that rentals are only available to students with access to a credit card.

Blackburn-Evans added that alternatives to the current model of assigning textbooks are on the radar of university administration.

“The university continues to investigate the suitability of reduced cost options for textbooks such as open source and/or commercially available e-textbooks,” Blackburn-Evans said.

Indeed, some professors have espoused similar thinking, turning to online and library resources as replacements for traditional textbooks.

Natalie Sommers, a third-year music student, noted a class experience that did not use textbooks.

“My teacher, Professor [Mark] Sallmen, posted all of the handouts and musical scores that we would be analyzing at the beginning of the semester [on Blackboard],” she said.

She added that, even though it was cost-saving, to use Blackboard as an alternative to a cohesive textbook, it had disadvantages.

“I ended up printing enough handouts out to form a textbook by the end of the year. Sometimes I would forget to check blackboard before class and found myself unprepared, as there were more handouts posted online,” Sommers said.

It remains unclear whether using Blackboard as a widespread alternative to textbook use is a suitable model to pursue in the future.

*Names changed at students’ request.