If you’re listening carefully, you can hear it. Amid honking cars, streetcar sounds, and pedestrian chatter, a melody weaves its way through the urban din. Though the downtown core may seem like a wall of noise, the sounds of Toronto include the soothing tones from buskers and street musicians adding harmony to the overbearing crashes of construction and traffic in the city.

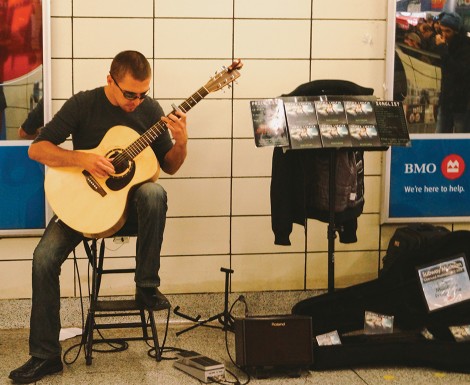

They make their music on street corners and in subway stations with the strumming of a guitar or the crooning of a saxophone. While we often pass these street musicians without much thought, with the exception of sparing an occasional coin or two, they provide us with a gentle ambience to help ease us through our tiresome commute.

While many street musicians busk in order to make a living, some simply do it to add some life to the monotonous atmosphere of downtown travel. Their sounds are varied and distinct, just as their stories are, and each has a reason for performing and bringing music to Toronto’s streets.

Red tape to performing

Subways are a prime locale for musicians. In 1980, the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) developed the Subway Musicians Programme — the program provided the city’s local talent with access to performance space inside the subway system for the first time. Since its development, the program has held auditions to select designated performers on an annual basis and issues performance licences to 75 individuals.

The Subway Musicians Programme reserves the right to refuse auditions from performers whose instruments and acts are not suitable to the subway environment — including the use of electric guitar or drum kits.

Each year up to 200 musicians apply for licences.

Musicians wishing to perform on streets in the city face similarly rigorous application processes. They must seek a permit from the city in order to be legally allowed to perform. Restricted areas include building entrances, transit stops, by postal boxes, or within nine metres of the intersection of two or more streets. Though these are the official regulations, a stroll down the major streets surrounding campus quickly reveals that not all performers abide by these restrictions — some simply take to the streets to play, permit or not.

David Rabinovich Spadina Station

David Rabinovich estimates that he has been busking for 22 years in Canada. He immigrated here from Russia, where he had already earned the title of a professional violinist. “I work for the people, and I want to make the children more educated, because it’s not everyday that they can listen to a professional violinist,” he points out.

In Russia, Rabinovich played in the symphony orchestra and received a master’s degree in violin, but immigrating to Canada presented him with several challenges. “I don’t want to wash dishes, I don’t want to drive a truck, and I don’t want to be a taxi driver,” says Rabinovich, adding, “Playing in the subway is not a personal decision… this is my way of surviving.”

Aside from busking, Rabinovich is also a part-time violin teacher.

Amanda Bloor Street West

Having played around the Annex for the past three years, Amanda has garnered a reputation throughout the area. “When I play down at Second Cup, I get a crowd around me,” she says. “The best thing for me is when I see people’s toes tapping, and then they start to dance… I’m out here to spread the happiness.”

But Amanda also has other reasons for taking up busking. “For me, it is for the love of music, but my husband passed away three years ago… so I grabbed a guitar and came out here, and this community has really helped me heal.”

While some days she busks to make money, most of the time Amanda says that she “just needs to come here and belt it out.”

Jason (Goldenfire Magic) Kensington Market

Jason’s career as a busker started off when he was a fire dancer/performer in Kensington Market, where he first developed his alias, Goldenfire Magic. As a street musician, he’s been playing for three years and does it mainly for practice. “I might as well practice on the street,” he says. “No one cares, and it’s good practice. It’s very grounding.”

Apart from using the time to work on his guitar skills, he also uses the opportunity to work on overcoming stage fright and anxieties about playing in front of other people. “That’s the magic of music, how it filters the mood. The more I’ve started to see how it affects people, the less I’m scared to play in front of people… I really like the intimacy of [busking], and the fact that it is very accessible,” he says.

Katherine Budb Bay Station

In the passageway between Bay Station and the Manulife Shopping Centre, Katherine Budb is seated against the wall with her German shepherd, where she plays the guitar for passersby. Her repertoire consists mainly of her own compositions, which come from her folk-punk band that she plays with on the side.

Budb has been busking for 15 years as a means of making money in order to successfully support her two children. When asked if she earns enough income as a street musician, she says, “Probably not ideally, but it’s more than minimum wage working at Loblaw’s, and fighting for hours, which is what I was doing before.” For Budb, busking is ultimately “a survival thing, something that I’ve always done.”

Andrew Lopatin Bloor Station

These days, Andrew Lopatin plays in the subway, mostly out of a sense of nostalgia, remembering the days when he would perform in the station to make a living. “I used to come here 12 hours a day five days a week,” he says. “I got a lot of opportunity from this. I got a lot of contacts… and now I go on tours once a year.”

Three years ago, Lopatin started busking in order to make an income out of something he enjoyed doing. “My whole life I’ve been 50/50 between two different passions, one’s cars and the other’s music. When I was 21 I auditioned to busk here… at the same time I was looking for a mechanic job, but I got a letter in the mail saying I have a license to play here, and that’s when I realized that this letter would decide whether I became a musician or a mechanic,” he explains.

Though he plays mostly for enjoyment and to bring music to others, Lopatin also busks for the sake of practice. “It feels good to be here,” he says, adding, “It’s the one place I know I can screw up all I want to.”

Robert Grant The Path, Queen Street EAST

“My prime reason for busking is that initially it started out as I was travelling, and I needed money,” says Robert Grant. Grant, a busker for the past 20 years, spent a significant amount of time busking in the US. For Grant, busking in America was the best option for him. “When you’re in the United States, and you don’t have a visa, you need to busk so that you don’t have to get hired anywhere, and you won’t have to show a social insurance number,” he explains.

When he came back to Canada, he was comfortable enough with busking to carry on with that job in Toronto. According to Grant, the money isn’t bad, and it is an enjoyable way to pass the time. “If you have a certain area that you go to, then the money is steady. People get used to you being here after awhile, and they enjoy hearing you,” he says.

Grant plays in the underground pathway almost every day, where he spends half of his time playing music and the other half chatting with pedestrians who pass by.