It has long been known that ancient water exists deep within our Earth’s crust, preserved in microscopic bubbles in the rock. However, a group of researchers led by Professor Barbara Sherwood Lollar from the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Toronto, has discovered that Earth’s most ancient waters exist in far larger and far older pockets than anyone previously thought.

“These waters range in age and the estimates range from about 1 billion to a maximum age of about 2.7 billion, about the same age of the rock,” says Lollar. “At that time, 2.7 billion years ago, in a period that we call the Archean, that part of the Canadian Shield was just like the bottom of the ocean now.”

As well as changing our understanding of how water is present in the Earth’s crust, by mapping where the oldest waters are accessible to us, Lollar’s work may reveal new secrets about our planet from very long ago. “This is the first time that anybody has been able to show that there are remnants of ancient components actually present within water that is flowing right back up out at you,” Lollar says.

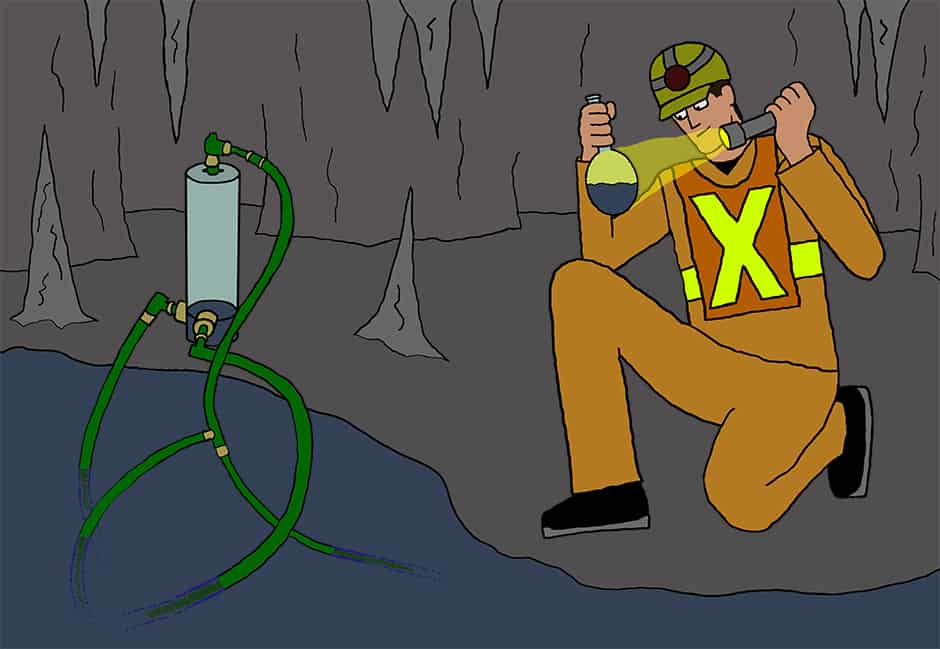

Lollar and her team have already taken samples from these ancient waters at various locations around the world where the water bubbles up from fractures in the rock, including here in Canada in a geological area called the Canadian Shield.

Analyzing these water samples allows geologists to get an idea of what sort of components the rock, water, and atmosphere on the surface may have contained up to billions of years ago.

What the team has found is that the water contained far higher levels of hydrogen than was expected. This is significant, because as scientists have already known from studying hydrothermal vents in the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean where light from the surface cannot reach, life can still be sustained due to the presence of this hydrogen, which acts as a food source for microscopic organisms, even without the ability to perform photosynthesis.

Lollar explains that the possibility of there being life in deep subsurface pockets is extremely exciting to geologists and biologists alike, as further studies on where life is and isn’t present can allow us to gain a deeper understanding of the sorts of environments that are necessary to sustain living organisms. Even if no life is discovered, the research is still extremely significant.

“It’s entirely possible that in these really ancient waters we’ll in fact find nothing living,” says Lollar, adding, “and that’s not a disappointment. That would in fact be very exciting as well, because that would allow us to test out the limits to life in the subsurface — why did we find life here, and not over there?”

Not only does the water interest biologists on Earth, but those seeking life in outer space will also benefit from the discovery. As it turns out, the rocks analyzed by Lollar and her team bear similarities to rocks that have been found on Mars.

“Working in the sites across the Canadian Shield that has similar mineralogy and age to the Martian crust, we see the production of the same kinds of reduced gases dissolved in the water as hydrogen and thereby accessible to microbes as a feedstock,” Lollar says. As such, any insight gained on the limits of life here on Earth may apply to other planets as well.