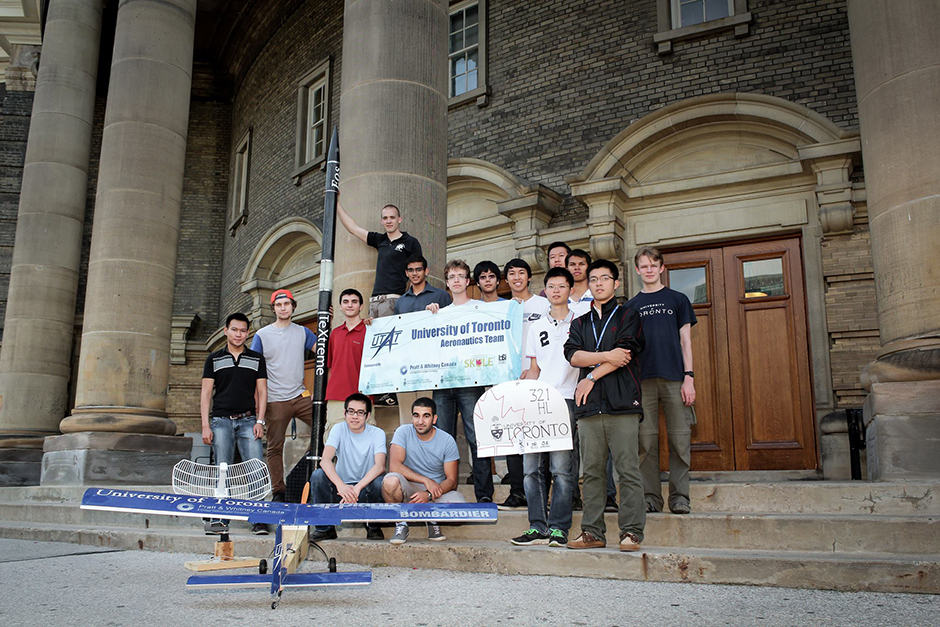

In the past, the University of Toronto Aerospace Team (UTAT) has taken on ambitious projects ranging from building unpowered glider aircrafts to launching rockets. Its newest and biggest project consists of building a functional small-scale spacecraft.

On January 10, 2015, the team will be opening its doors to academic leaders, industry professionals, and the general student population for a product review of the spacecraft in progress at the Galbraith building.

As the largest student design team at U of T, UTAT is completely student-run and engages about 100 active student members every year. It is separated into divisions, with the Space Systems Division heading the project of building the small satellite. With this project, the group will be competing in the Canadian Satellite Design Challenge in the near future.

UTAT president, Jeffrey Osborne, says that the team is trying to create a small satellite that can be launched into space to investigate the changes that occur in the human body in outer space. The human immune system is vulnerable and can fall prey to the harsh conditions of space.

The team hopes to tease out the differences between the specific responses of different microorganisms within the human body to the change in environment. Certain bacteria that are a part of the human body and live in a symbiotic relationship with humans, without harming us, are known as commensal bacteria. Those that are a part of the human body and do not harm us unless our immune system is compromised are known as opportunistic pathogens.

Osborne says, “One of the things we are particularly interested in is how do these different micro-organisms that we know to both be opportunistic as well as commensal to humans react to space.” He hopes to “better understand the risks that opportunistic commensal organisms pose to human health in space.”

He expands, “Small satellites offer a lot of potential for becoming a standard in how we perform this type of research.”

The team consists of U of T students — both undergraduate and graduate — with collaborating students from universities in Montréal and across the globe in Australia.

The group also has a number of partnerships with industry groups that give insights on the designing of the project and is the source of product donations, as well as partnerships in the academic field both inside and outside of U of T.

Using an approach based on the Agile Manifesto, common in software engineering, the team is operating on fast-paced four-month cycles. They present the functionality of the system at the end of each cycle to receive feedback and catch flaws in the system early on. The team has just recently completed their first cycle called the “Basic Functionality” iteration.

To the team, obstacles have become somewhat of a norm. “…Everything is going to go wrong at some point,” says Osborne. He adds, “The hardest part of a project is understanding these hiccups will happen, trying to anticipate them, trying to prepare for them, and being able to recover when they do happen.”

Although the end to the project will be marked by the successful launch of the spacecraft, Osborne says, “The goal is really to demonstrate that a group of students can build, launch, and operate a spacecraft.”

“Currently, there has not been a single student-built satellite launched from Canada,” says Osborne. He believes it is possible for UTAT to launch one spacecraft every three years, given a reasonable amount of funding and resources.

“Come to our school,” Osborne says, “[and] by the time you leave you can launch a spacecraft. We would be offering students an experience that is unparalleled in this country.”