A city is a patchwork of narratives. It is the juxtaposition of people and places — each with its own history — that shapes the metropolis around us. Toronto is an urban centre in the midst of rapid development and expansion — construction in the name of progress clogs the streets and cranes dot the skyline as you drive into the city. In constant flux, the city’s image develops more and more into a glass and steel metropolis.

Tucked between the towering office buildings and new, impressive condo developments are smaller buildings composed of brick, dwarfed in comparison to their behemoth neighbours. Though not as clearly representative of the city’s identity as icons like the CN Tower and Honest Ed’s, these landmarks have left marks of their own on the city’s development. Dozens of them have been granted heritage status, while others have been torn down and replaced with newer, more functional structures.

Whether they have weathered the tide of expansion or have been replaced in the name of progress, some buildings are as integral to Toronto’s composition as the people that reside within them. We took a look into the rich histories of some of the significant buldings on and around campus to situate some of the landmarks students see every day in the evolving architectural tapestry of Toronto.

MENTAL HEALTH IN HISTORY

For those hurrying along Queen Street West in an attempt to avoid the sting of winter winds, this landmark can easily be overlooked. In the city’s west end a span of historical wall runs along the exterior of the property outside of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH).

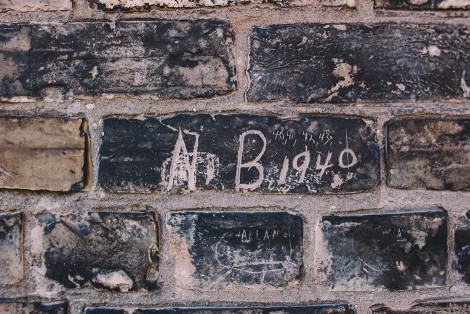

Though adorned with plaques outlining their historical significance, the walls themselves are unimpressive on first glance. Upon a closer look, the bricks quite literally tell a story. Many are imperfect, though the imperfections are not all a product of their age. Many have deliberate markings: words, phrases, and Xs gouged into the brick.

The walls and the messages inscribed upon them are the work of patients in what was once the Provincial Lunatic Asylum. Constructed in 1850, the large institution once occupied the lots of present day 999 and 1001 Queen Street West. The official address of the asylum was 999 — a number that came to be synonymous with insanity and mistreatment.

The walls themselves — once 16 feet high and surrounding the perimeter of the asylum — were the work of patients in fulfillment of the labour portion of their treatment. In 1850, theories about how best to treat the mentally ill were changing, largely moving toward a consensus on the value of “moral therapy.” This treatment advocated a strict daily regime that incorporated manual labour.

To afford for this type of treatment on a large scale, the province constructed a massive asylum — at the time of its completion, the Provincial Lunatic Asylum was the largest non-military public building in Canada.

Today, the only remaining components of the original structure are the walls.

The walls bear scars of those days of mistreatment, and today serve as a monument to the patients who existed behind them, intentionally hidden from the world. The walls hid the conditions of the institution, which were squalid — a product of over-crowding and inferior sanitation systems — conditions there led to the rapid spread of disease.

Over the course of the past several centuries, the Provincial Lunatic Asylum evolved, along with approaches to mental health. In the course of its transformation from the horrors and neglect of the past to the centre that resides on the land today, the institutions that have occupied the land have changed drastically in architectural style.

Although CAMH has carefully separated itself from the site’s questionable past, it is mindful of this dark history. Perhaps most symbolic of the dichotomy between past and present is the change from the original 999 Queen Street West address to the current 1001 Queen Street West address that CAMH now occupies.

A BEACON IN THE NIGHT

Pausing at the corner of Spadina Avenue and College Street, the red façade of The Silver Dollar Room stands out against a spectrum of greys. The paint is chipped in some places, discoloured in others — saturated panels of red mark where bills were posted shielding the paint from the effects of the sun.

This windowless building is not an impressive spectacle in the traditional sense. To learn that it recently received a heritage site designation could easily be seen as surprising: there aren’t many music venues in the city that have earned such a protection, let alone one as seedy as The Silver Dollar Room. For students at the University of Toronto, the venue is probably most known for its iconic sign and its presence at the edge of campus on Spadina, just north of College.

Opened in 1958, the venue was conceived as an upscale lounge for the neighbouring Waverley Hotel. In the decade that followed, that image was dashed as the venues reputation deteriorated. After a brief stint as a strip club, it became a popular music spot. Many acts have graced the stage, from local Toronto artists to some of the biggest names in the industry, including Bob Dylan. For more than 50 years, crowds of concert-goers packed into the venue night after night. This popularity opened its doors to a history of performances and a legacy as a Toronto landmark.

The iconic sign affixed to the front of the Silver Dollar has lit the College and Spadina streetscape in neon for half a century — with the exception of 1992 when new owners briefly rebranded the venue.

Indeed, the resilience of The Silver Dollar Room is perhaps what sets it apart. It occupies prime real estate in a burgeoning city and has been threatened with the wrecking ball more than once. One recent building proposal suggested tearing down the venue and the neighbouring Waverly Hotel in order to create additional student housing.

Having recently been granted heritage status, the venue now has some additional protection against developers. Nevertheless, like many iconic Toronto landmarks, the future of The Silver Dollar Room remains uncertain in the face of the rapidly changing city.

A SHADOW OF A LANDMARK

Located at the corner of Harbord Street and St. George Steet, the grey, drab Ramsay Wright Laboratory building appears unremarkable. The most interesting aspect of the building is quite possibly the land that it occupies. Long before the building was constructed, this street corner was part of a small, well-groomed neighbourhood adjacent to a then much more compact University of Toronto campus. In those days, trees rose above many of the city’s buildings. Now, surrounded by towering structures of metal and steel, it’s hard to imagine that apartments were ever a novelty in the city. It was, however, on this site that Toronto’s first apartment building was erected.

Called the St. George Mansions, the building was completed in 1904 and consisted of 34 apartments with a combined maximum occupancy of 99 people. The units were marketed to wealthy Torontonians, and their construction marked an important shift in the city’s architectural developments.

Later, during World War II, the building was repurposed for the war effort; the mansions became the Trinity Barracks, the Toronto base for the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. During this period, the building fell into neglect. Evelyn Jamieson, a member of the corps, described the barracks as “cockroach palace.” After the war, the building had become so dilapidated that it was torn down. The Ramsay Wright building eventually replaced it, erasing all signs of the landmark that once existed in its place.

ARTISTIC LEGACY

Nestled north of the intersection of Yonge Street and Bloor Street is an unassuming three-storey building. It is not particularly remarkable for its design — it is, essentially, a rectangle of red brick with a flat roof. From the outside, the building is little more than a bulky cube. The only compelling architectural feature is the two columns of bay windows adorning the front walls of the building that divide the monotony of brick. The windows are large, letting light in to illuminate the rooms.

Light would be of particular importance for some of the historical residents of this building. The Studio Building, located at 25 Severn Street, was once the studio space of The Group of Seven, perhaps Canada’s most well-known artists.

The building itself was constructed with art in mind and was intended to be a working studio space. The building contains six studios which have been inhabited, at one point or another, by some of the most recognized names in Canadian art history.

The purpose-built space was designated as a historical site in 2004, partly because it continues to represent a foundation of sorts for Canadian visual art and a meeting place for young artists who had a profound impact on the development and vision of Canadian art.

CHAOS IN THE STREET

To many of us, the looming apartment building above G’s Fine Foods is not noteworthy, except maybe to comment on its generally unappealing, dated appearance

The building, now apartments, was once the home of an experimental initiative in cooperative living and alternative education. Rochdale College, established in 1964, was Canada’s first free university and a residence for the University of Toronto. The classes were student-run and degrees were not reputable: they could be obtained for a fee and the successful answering of a skill-testing question.

When Rochdale was established, the Bloor Street West and St. George Street area was a very different place; the now-affluent Yorkville was, at the time, a gathering point for hippies. The co-op became a haven for creative and unique minds — a collective for artistic and philosophical thinking.

Though borne out of good intentions, the co-op quickly spiralled out of control. A 1969 surplus of student housing at the university opened Rochdale’s doors to a more varied population. By the early 1970’s, the co-op had changed drastically. It became known as a crime hotspot and drug haven. In 1974, a riot broke out, which culminated in bonfires burning in the middle of Bloor Street.

In 1975, the co-op was forcefully closed. Remaining residents were carried out, and the doors were welded shut. The building remained vacant for many years.