Brian Langevin was introduced to asexuality at 16 years old, when his friend came out to him.

“I had for quite some time not identified with the traditional sexual community and finding the asexual website AVEN [the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network], the definition on there just really clicked with who I was,” he says. Langevin, now a first-year student at U of T, has identified as asexual ever since.

Noting a lack of educational material on asexuality, Langevin decided to make a weekly series of informative videos on YouTube. His channel, Everything’s A-Okay, provides an introduction to sexual orientations towards the asexual end of the spectrum, as well as related subjects such as romantic orientations, asexual relationships, and research around asexuality. In addition to his work on YouTube, he is a co-director of Asexual Outreach, a non-profit organization set to host the North American Asexuality Conference in June 2015.

According to Julie Decker, an asexual author from Florida known online as swankivy, asexuality is gaining more and more visibility and recognition worldwide. “People have heard of it somewhere, they’ve seen it on TV, they’ve heard it mentioned,” she notes.

“I don’t think that maybe 5-6 years ago I could have gotten a book deal on the subject, but I really think the tides are turning,” Decker says. Her book, The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality, was published in September 2014.

ASEXUALITY 101

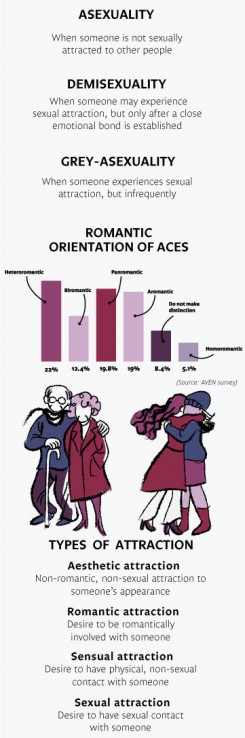

Asexuality — most commonly defined as not experiencing sexual attraction towards people — exists on a spectrum, which includes varying degrees of sexual and romantic relationships. Together, the spectrum is sometimes referred to as the “ace umbrella,” with “ace” being an abbreviation for asexual. People who use any one of these terms to describe their orientation may or may not refer to themselves as ace. This article uses the term ace when referring to people on the asexual spectrum and asexual when referring to asexuals specifically.

Asexuality — most commonly defined as not experiencing sexual attraction towards people — exists on a spectrum, which includes varying degrees of sexual and romantic relationships. Together, the spectrum is sometimes referred to as the “ace umbrella,” with “ace” being an abbreviation for asexual. People who use any one of these terms to describe their orientation may or may not refer to themselves as ace. This article uses the term ace when referring to people on the asexual spectrum and asexual when referring to asexuals specifically.

A person’s behaviour is not an indication of their sexual orientation. For instance, asexuality and celibacy are different things, but there are many aces that choose to remain celibate. Yet, there are also aces who have sex for a variety of different reasons.

The way in which people experience asexuality differs from person to person, and many aces have to defend their identities when non-asexuals try to invalidate or refute them, often relying on harmful and inaccurate stereotypes to do so.

When Langevin came out to his family, they asked him a lot of questions. “My dad actually asked me if I had been abused as a child. It’s difficult because someone will counter with ‘Oh, that’s just a phase’, and they’ll counter with ‘Oh, it’s a mental condition,’” he recalls.

Not everyone has equal access to an ace identity. Aces who have been abused and/or experienced violence or trauma; aces whose sexuality is fluid; aces with disabilities and/or mental illnesses; autistic aces; and aces of colour or from racialized communities are systematically excluded from the basic definition of ace orientations and even the ace community itself.

“There’s a massive stigma,” says Queenie, an asexual blogger and survivor of sexual violence. She began writing about asexuality and sexual violence in 2012. “I started writing about it because I had experienced it, and there wasn’t anyone around talking about the experience that I had had, and I felt that someone needs to do it,” she says.

Queenie described her experience on a panel a couple of months ago, which opened with the statement “No ace has ever experienced sexual violence.”

“It becomes so pervasive as part of 101, that we’re not broken or ill or the result of trauma, that [it] erases aces who are mentally ill or disabled or have survived trauma,” she says.

When asked what contributes to the exclusion of ace survivors, Queenie says that the idea of the “unassailable ace” — a person who is the perfect or ideal ace — plays a role, alongside pressure from the community to keep silent about experiences of sexual violence to avoid confusing people who are not asexual.

“That makes aces who have experienced sexual violence feel like they’re not ‘allowed’ to identify as asexual, or if they’re going to identify as asexual, they need to stay silent about their experiences or else be kicked out,” says Queenie. She points out that narratives of sexual violence are often only mentioned when somebody wants to win an argument about whether or not ace people are oppressed.

“You probably don’t feel particularly welcome or inclined to talk about your experiences, especially if you don’t fit into the model survivor narrative that makes your experiences useful for winning arguments,” she says.

Johann*, a third-year asexual student at U of T, was sexually abused as a child. “There’s always a possibility that that’s involved; you have to acknowledge that I can’t reject that, I can’t. To some extent I do think about that, but it doesn’t really bother me, it doesn’t make me anxious, I don’t really care, I’m okay with it,” he says, adding, “If someone offered me an opportunity to fix it or change it, I’d go ‘Hell no! I don’t want that!’”

ACE ATTRACTION

The ace community created the language used to differentiate different types of attraction, which may include sensual, aesthetic, intellectual, sexual, and romantic attraction. For some people, these types of attraction align. For others, they are distinct. Generally speaking, sexual orientations have a corresponding romantic orientation.

Arianne* is a fourth-year U of T student and an asexual lesbian. “I like the word ‘lesbian.’ It has a lot of history behind it,” she says of her choice of language. “When I’m talking about my sexuality, that is usually the only information I need to give.”

Arianne describes herself as a very private person. “The asexual part is more personal, it’s more private and I don’t think the two are in conflict with each other. The fact is that I would only ever date a girl, and that is the important part. The sex part is between me and my partner,” she adds.

She says that the lesbian community is very sex-focused, due to the way in which lesbian relationships are often construed as friendships. “To say that I am a lesbian but I don’t like sex, you feel the pressure that ‘doesn’t [that] just mean you’re friends?’ because things like cuddling and hand-holding and even kissing sometimes are considered friend things between girls. And that’s not what it is, but it’s how that’s perceived,” she says.

Decker is aromantic, which means she does not experience romantic attraction. For her, being asexual and aromantic have always been intertwined. Decker believes that her life would be significantly harder if she wanted a romantic partner and therefore had to negotiate sexual compatibility and compromise. “For romantic asexual people, my heart goes out to them because so many of them experience difficulties in their relationships,” she says.

Being aromantic has its own set of challenges. “As an aromantic person, I am processed by the outside world as cold and unfeeling, as if there’s something really broken at the centre of my being. Which is funny because most of the people who know me would never process me like that. I’m a very affectionate person who does so many things and has a zest for life so to speak, so it’s really laughable to define a zest for life as being joined to sexuality and to romantic attraction, because for me it is not,” Decker says.

Queenie tends to use the term “queer” to describe her romantic identity because it is easier for people who are not familiar with ace community terminology to understand, and it is sufficiently vague. “Pinpointing my exact romantic orientation tends to be an exercise in frustration more than anything else,” she says.

“If I were to be really specific, biromantic is a good approximation gender-wise and either demiromantic or greyromantic [romantic orientations that correspond to demisexual and grey-asexual] captures the weird fuzziness. I’ve started self-describing as biromantic more recently, mostly because I’ve gotten involved in some bi communities. But queer is still usually what I go with,” Queenie explains.

Johann says that the fact that he has never been in a romantic relationship makes it difficult for him to pinpoint his romantic orientation. “I’ve never been in any sort of romantic situation, so I don’t have the necessary experience there to be actually certain… I’m not picky, you know. Mostly lasses, but not a rule. I’ve been attracted to men before, not a big deal,” he says.

However, Johann does not think it is necessary to have sex in order to actually be certain. “Sex and romantic relationships are different things. You have sex, then you’re done. But when you’re in a romantic relationship and it’s long-term, it’s a commitment and then there’s all the emotional crap. They’re completely different experiences,” he says.

“I think it’s a different thing to say that I haven’t had the necessary experience to talk about romantic relationships than it is to say I haven’t had the necessary experience to talk about sex,” he adds.

RELATIONSHIPS AND DATING

There are a variety of ways in which aces have relationships. These include relations with friends, family, their communities, romantic relationships, and queerplatonic relationships. The latter refers to an intense non-normative relationship that is not romantic, but not adequately described by friendship.

Here, “relationship” does not denote sexual or romantic exclusivity; it indicates that you have somehow interacted with someone, or continue to interact with them.

When ace people do date, their romantic relationships can take many forms: monogamous or polyamorous; long-distance or online with other aces; or a “mixed” relationship, wherein ace people date others who are not asexual.

Although Decker is aromantic, she did date in high school, partially because she still believed that she would change eventually, and partially because people pursued her insistently. “I gave it a try, but it really wasn’t anything that I was really doing for myself. It was more from an outside pressure, and it was definitely a frustrating and stressful experience,” she says.

Decker experienced the same thing at university. “People wanted to date me, people were very petulant about it if I didn’t seem interested in them. Sometimes they would get confrontational about it, which is probably the first sign that you don’t want to date that person even if you do like a particular type of person in romantic and/or sexual relationships,” she says.

In university, Decker did not date anyone because she did not develop any interest in it. She was ridiculed and harassed for her aromanticism. “I had one guy try to kiss me after I said no, that sort of thing. There were people who believed that they could fix me, and there was a lot of that narrative when I was in college: ‘You haven’t experimented enough,’ or ‘I’m going to show you.’ That was scary.”

University is a prime time for prominent sexual experimentation. If you don’t participate in such activities, Decker says, you can be framed as close-minded or unadventurous. “That happened to me,” she shares.

Langevin, who is homoromantic, says that he expects to end up with a partner who is not asexual, both because the dating pool of asexual homoromantic males is small and because it is common for asexuals to end up in romantic relationships with people who are not asexual.

For now, Brian is content with the relationships he has at the moment. “I am not lonely in the sense that I have close friends, I have acquaintances, and I have all these people who I can go to. I have a good number of close friends, and I really have relationships with a large number of people. Not in a romantic sense, or a sexual sense, but relationships meaning I have a connection with them and we can talk and hang out,” he says.

THE A-GENDER

Gender diversity is common within the ace community. According the 2014 AVEN census, around one in five aces are trans or otherwise gender variant.

Arianne has yet to come up with a word to describe her gender. She is still comfortable using the word “lesbian”, which has a strong female implication. However, things that are generally important about gender and its distinctions have never been particularly important to her.

“It doesn’t seem terrifically necessary for me to respect the codes and expectations of gender. I like to wear suits as much as I like to wear dresses and so I don’t have a good word to describe what I think. I think there’s something there to be explored,” she says.

Speaking to the high proportion of gender-variant aces, Arianne says, “It has something to do with the fact that sex does place certain expectations upon us, and when you’re already in a frame of mind where you’re rejecting expectations the world is putting on you, you may be a little bit more open to exploring, rejecting some of the other expectations too, particularly those surrounding gender. I think that’s where I am now.”

Decker says that her asexuality is definitely affected by being a woman. “Female sexuality is sometimes just expected to be passive, I think, and I have dealt with an absurd number of men who say, ‘Asexual? That’s not a thing for women. All women are sexual, you’re not supposed to be, give it up.’”

She remarks that guys sometimes react to asexuality as if it doesn’t really matter what a woman feels in a relationship. “[They think] she’s just supposed to be there for the man, which I find to be horrifying and of course chauvinist and sexist. I’ve encountered that an awful lot and it’s definitely a different experience for an asexual woman [versus] an asexual man [versus] someone who doesn’t identify as male or female, but gets sorted into boxes,” she comments.

WHERE IDENTITIES INTERSECT

There are any number of intersecting identities, other than gender, that influence how someone experiences being ace, including race. Queenie is working on a blog post about being asexual and Latina, which she has been writing for around six months. She finds it harder to talk about this aspect of her identity because she has not seen other people talking about it and therefore does not have a good sense of whether her experiences are different from the norm.

“When it comes to writing about other experiences, I feel like I have someone else to point at to say, ‘No, look, it’s not just me!’ but I don’t have that in this case. But I feel like it’s something that needs to be talked about, because it’s a weird intersection to exist in and people tend not to treat it with as much respect as they should,” Queenie says.

Queenie further considers the intersecting factors that came into play regarding the sexual violence she experienced. “It is really hard to try to figure out what exactly caused my experiences of sexual violence… In the first instance, asexuality probably played a role. The fact that I was attracted to women also probably played a role, since my boyfriend was obsessed with the idea that I’d leave him for a woman. Did race play a role because he expected me to be hypersexual? Maybe. It’s really hard to say.”

When Johann tried to explain asexuality to his father, he refused to believe it existed. “He tried every fricking excuse in the book,” Johann remembers. “He once claimed that I couldn’t be asexual because I’m Greek and ‘Greeks aren’t like that.’”

Discussing the place of sex in different cultures, Johann says that, in Western culture, you have sex to have children. “You’re supposed to stop once you’ve had them. In Greece, you keep going until you die. Ninety-year-old people go at it, you know,” he says.

Johann says that he currently does not feel the pressure to engage in sexual relations. “I was just reading an article about how noone’s dating because of the economic crisis, so no, but maybe if the economy were better,” he speculates.

Johann says that it is certainly a challenge when he encounters people of older generations who aren’t as open-minded as they could be. “But I do think it’s changing and I do think it’s going to be better for us.”

*Name changed at student’s request.

This article uses statistics from the 2014 AVEN survey, which excluded ace survivors of sexual violence. Queenie has written extensively on how it does so, and she believes that it is part of the larger issue of not wanting to acknowledge sexually violent experiences in ace communities; if hard numbers exist, people can’t minimize or maximize the issue as they see fit.