Ontario’s recently revamped sexual education curriculum has polarized the public. Among the variety of signs raised and slogans chanted during the protests at Queen’s Park last month, two factions took form: a vehement disapproval of the state’s incursion into the family’s domain of influence and a gleeful hope for a more sexually aware youth.

Disgruntled protestors held signs with slogans like “math, not masturbation; science, not sex!” whereas others applauded the move with slogans like “ignorance endangers children!” CBC reports that the new curriculum — which hasn’t been revised since 1998 — is the most up-to-date one across the country. Applying to grades one through 12, the curriculum is more representative of the demographic, technological, and cultural developments of today’s society than its predecessor. The policy’s redesigned structure not only encourages tolerance and inclusive dialogue, but also seeks to educate young students on pertinent social issues in Canada, from sexual violence and consent to sexting and digital privacy.

Much of the uproar has centred on the classic problem of governmental overreach. To what extent should a government-mandated program of sophisticated sex-ed complement the private role of the family — the latter, supposedly, being the primary socializing institution? While this is a relevant concern, I believe that it actually overlooks the more important controversy at hand: the basic purview and purpose of education itself.

The overall success of any cosmopolitan educational system lies in its capacity to self-renew in accordance with our expanding body of knowledge about the world and with the multifaceted development of the society surrounding it.

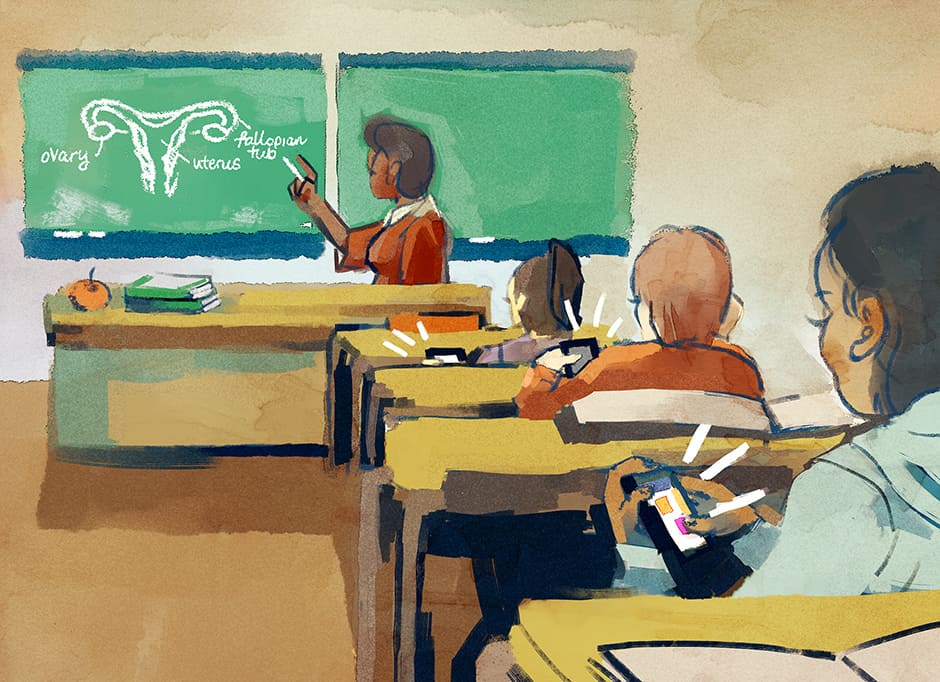

Albeit sensitive and often contentious, sexual education is an interdisciplinary form of education. This ongoing debate, certainly not the first of its kind in the province, reflects an implicitly held assumption that sexual education is somehow inherently distinct from the domains of knowledge that collectively constitute it.

Yet, sex-ed is inseparable from the areas of reproductive physiology, anatomy, epidemiology, virology, gender sociology, affective psychology, cultural anthropology, and pharmacology, to mention a few. With this complexity in mind, the rationale behind the updated organization and distribution of lesson expectations becomes clearer.

In response to the aforementioned protest slogan, I would say that mathematics and science are in fact part and parcel of a comprehensive sexual education. We must ask, then, why should sex-ed be circumscribed or cherry-picked? Of what benefit is a deliberate deferral of some of the most basic lessons about human sexuality? If all curricula are subject to renewal, lest they become anachronistic, sexual education shouldn’t be considered any differently.

Delivered and discussed as objectively as possible, the curriculum can act as an empowering tool for intrapersonal and interpersonal success. It is easy to conflate objective facts and social realities with moralizing tendencies.

For instance, it is one thing to raise awareness of the gender spectrum or varying sexual orientations, and another thing to profess the dominance or inferiority of some variants over others. The same goes for sexual habits and practices. Hence, a constructive sexual education curriculum merely provides the pupil with a knowledge toolkit, which serves to improve and refine their decision-making. The application of the curriculum next September should be as detached as possible from the value-laden realms of ideology.

My assessment of the value of the recent changes also derives from local and global considerations. Youth are often among the first adopters of new consumer technologies as they become available. Almost all high school students in the province have a smartphone in their pocket and a Facebook or Twitter account, each of which afford them abundant opportunities to communicate with their networks, check in with friends, post photos, and more.

Participation in these global and local networks has never been easier, and the accompanying risks have never been more conspicuous — one need not look further than the sexualization of photo-messaging mobile applications. Does this not highlight the importance of educating young students about sexting and the privacy-related dangers associated with sharing explicit content online?

Today’s youth, caught in the midst of the ebb and flow of the twenty-first century, are in need of a modern and versatile sexual education curriculum that succinctly addresses the challenges of a rapidly evolving society. Overall, it seems to me that the new curriculum is reasonable.

Omar Bitar is a fourth-year student at University College studying neuroscience, sociology, and biology.