We are in tumultuous times here at U of T: classes are being cancelled, assignments are being discarded, and final exams are being reweighted. The extent of the damage is so widespread that you’d be hard-pressed to find an undergraduate not affected in some way by the CUPE 3902 Unit 1 labour strike.

Although the damage caused by the strike has been undeniable, many students are coming to terms with the fact that their assignment will most likely be skimmed, if read at all, by their professors.

The CUPE 3901 Unit 1 strike has provided the rare opportunity for students to observe and comment on the efficacy of how the university is keeping its students in the loop about the current state of affairs.

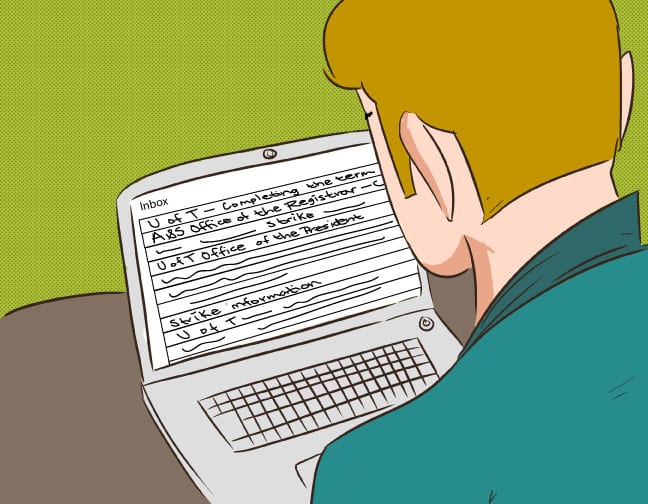

In this respect, U of T has failed miserably. The university bombarded our email inboxes with subtle propaganda towards their cause — these emails and bulletins have had the opposite effect on garnering student support for U of T’s limited bargaining with CUPE 3902 Unit 1, as the content of these emails has been transparently biased and contradictory.

Take, for example, the first email U of T students received on February 27, day one of the strike. The message, between inferring that picketers would be confrontational and belligerent towards students, also included a weak offer of reassurance by stating that although the university “places a very high value on maintaining the integrity of [its] academic programs,” courses, grades, and moving forward toward the end of the semester, there would be “difficulties or confusion” as the university attempted “to establish alternative arrangements for some courses.”

The rhetoric of this message, while purposefully vague and belittling, is also inherently indicative of the nature of communications between the administration and its students. Email, while good for reaching out to the entire student population easily, is an old and ineffective technology that needs to be scrapped as the primary mode of communication between students and the administration.

These emails lose their resonance with students because we’re bombarded with several of them a day from multiple university organizations — how these clubs and organizations gain access to our personal email addresses is another story — but the ping of a new message from U of T in our inboxes is white noise to students who have moved on to more effective modes of communication.

That being said, the university has taken some steps to improve communication with students. The UTAlert service provides students who register with a text message informing them of an emergency.

Although the system doesn’t clearly state what warrants an “emergency text,” I would argue that the service would be better suited to informing students about non-weather related, less dire situations — like honest messages about the status of our courses, specific information about negotiations with CUPE, and links to further information.

Trying to gather information from U of T shouldn’t be as difficult as it currently is. Not enough is being done to effectively communicate with students — we’re constantly being directed and redirected to various people, websites, and hotlines in order to get a straight answer.

On the other hand, the TAs and CUPE 3902 Unit 1 have got it right. They are a huge presence on multiple social media platforms, and the rhetoric they’re using to communicate with students and the community via these platforms is not only informative, but comprehensive as well.

If U of T wants to garner support from and cease alienating its undergrad students, the administration needs to re-evaluate and immediately update the rhetoric, methods, and mediums they use to communicate with us — then maybe I’ll stop sending everything to “spam.”

Emma Kikulis is an associate comment editor at The Varsity. She is studying sociology and English. Her column appears bi-weekly.