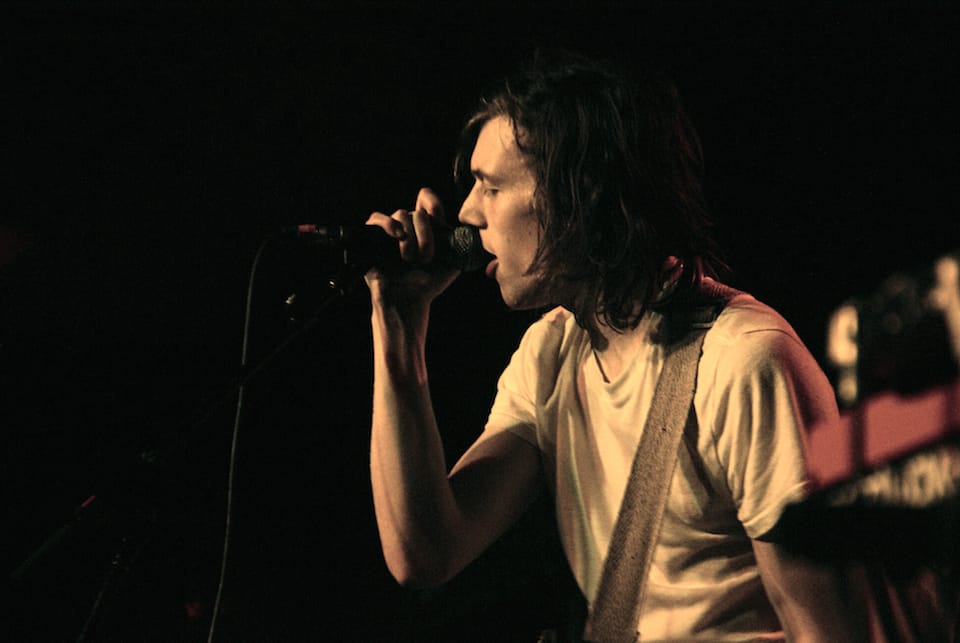

The sounds of Tokyo Police Club’s Forcefield (2014) reverberated against the walls of the Danforth Music Hall; the concert was a celebration of modern, light-hearted synth. Suddenly, the lights dimmed, and the crowd fell silent. Front man Dave Monks began to play an acoustic rendition of an early song entitled “Tesselate” — the sound was meditative, and honest.

Six months later, Dave Monks announced his solo project — a seven track EP entitled All Signs Point To Yes, to be released June 16. The record is full of catharsis, which Monks is quick to point out during our conversation.

The album is driven by a primarily acoustic sound, and its production is simple. The unnecessary adornments of alternative pop have been removed, leaving only the undercurrents of the band’s sound. All Signs Point To Yes isn’t meant to be part of the same discography as Forcefield; it has it’s own unique sound. “It was freeing,” explains Monks. “You have to have different projects going on so that you have different outlets. I still like doing loud pop stuff, but it’s hard to put them all in one spot.”

As illustrated in the track “Gasoline”, there are no overly poetic sentiments in Monks newest project, but instead direct and honest lyrics take centre stage. Lyrics such as “lovers fall and break their hearts / but I need one to keep,” encapsulate this. There is vulnerability to be found in the record’s acoustic simplicity and subdued vocals. The foundations of the record are personal to the extent where the album verges on becoming a form of musical annotation to the musician’s life. “I just started [writing the EP] and I thought no one would care, no one was looking and that was what was exciting,” he explains.

The record is cathartic in its articulation of transitions for Monks, such as his move to Brooklyn. When I ask him about this, he pauses before telling me, “Everything changed.” Expanding further, he notes the differences he noticed after moving to New York. He credits his newfound love for Brooklyn to the sheer amount of creativity that lies within the New York borough. “There’s a little more going on here,” he says. “[In Brooklyn] the artist mentality is to stay busy and to try new stuff.”

In fact, Monks has taken a liking to Brooklyn to the point where he feels more at home in the U.S. than in his hometown, Toronto. “Now when I go back to Canada, I check off the visitor’s box on my custom card, rather than the resident box,” he says.

Monks spoke to the continual collaborative structure of his record, both in his work with producer Rob Schnapf and the relationship Monks maintains with his audience. The album is conversational, articulating the uncertainties and vulnerabilities of a transient time in Monks’ life to the listener.

Monks explains, “I get this impression that in order to be a good creative person, you never have to ask anyone for their opinion, [because] your art is your art. But I think a lot of really great and talented people do, in fact, ask.”