Content warning: Discussions of sexual assault

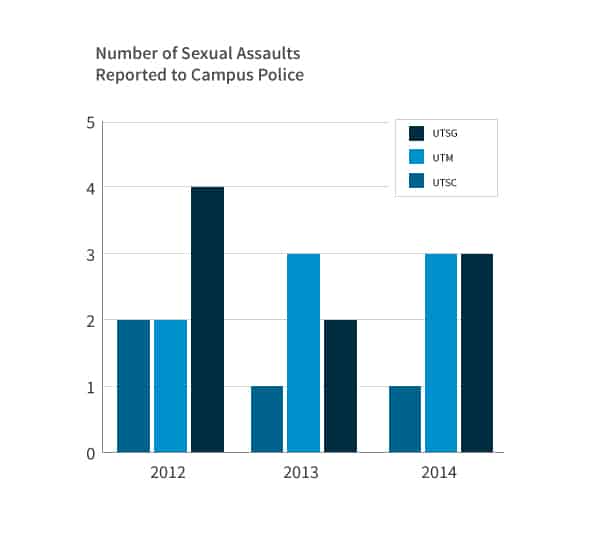

Recent annual Campus Police reports state that only seven sexual assaults were reported across the University of Toronto’s three campuses in 2014. During both 2013 and 2012, the total number was six. Sexual assaults are known to be much more common than police reports indicate; other forms of sexual violence are excluded from these reports altogether.

These reports reflect the number of assaults that were reported to Campus Police, however, there are many different channels through which a student can report an assault. These include reporting to the Campus or municipal police, via the U of T Code of Student Conduct, as well as informal reports to a counsellor, residence don, or other support services.

“Disclosures are not recorded for statistical purposes, as it is important to ensure that an individual’s disclosure can remain confidential if they would like it to,” said Althea Blackburn-Evans, director of news & media relations at U of T.

Reporting systems in place

On paper, U of T’s administration has a robust system for responding to reports of sexual assault. To formally report an assault and have it investigated under the U of T Code of Student Conduct, students must first go to representatives of their college or professional faculty.

The Varsity spoke with administrators at several colleges and professional faculties about the structures in place at their divisions. All of them expressed confidence in their respective support services.

“A student who reports a sexual assault is taken extremely seriously,” said Liza Nassim, dean of Woodsworth College. “We provide a caring and supportive environment, we listen, and we try to be as supportive as possible and provide relevant resources.”

For her part, Sarah Baker, director of public relations for the Faculty of Kinesiology, said that the Faculty of Kinesiology partners with U of T’s Health and Wellness professionals to deliver annual violence prevention training for students, faculty and staff, including orientation leaders, coaches and student-athletes. Some colleges, such as University and Woodsworth, also ensure that their Orientation Leaders are trained in sexual assault awareness and prevention.

Ryan Woolfrey, associate registrar of University College, said that his office is a well-known student resource. “Our office is known and widely promoted as a reliable first stop to assist students with any issues they may be facing,” he said.

Students, however, do not appear to share their administrators’ confidence in faculty and collegiate services. Katrina Vogan, founder of the U of T Thrive Initiative, said that 44 per cent of respondents to the Thrive survey circulated earlier this year, agreed with the sentence “I have chosen not to go see somebody for help at U of T because I felt like they would not understand me.”

Celia Wandio, founder of Students Against Sexual Violence, agrees: “the problem is that U of T itself has not made an effort to properly collect this data.”

Why don’t survivors report?

The reality of reporting is more complicated than the university’s policies indicate.

Anjali*, a student at Trinity College, noted that reporting was not her first instinct. “The main reason I decided to report was because I found out that the same individual who had sexually assaulted me, assaulted someone else I knew. Before I heard about another case, it did not cross my mind to report.”

Despite feeling supported by the Office of the Dean of Students at Trinity, Anjali said that her case is ongoing, months after her initial report. She does not know whether the perpetrator has been informed at all. “[It feels] as if the university will say ‘Hey look you can see that we tried to help you as best we can, but we still won’t take any effective action against him.’”

Jane*, a student at University College, was similarly disappointed with her experience reporting to Campus Police. She reported an incident wherein she was walking along St. George Street when a man on a bicycle reached out and grabbed her before speeding off. When Jane informed campus police, they sent a member of the Toronto Police Force to her residence door unannounced, and since that day several months ago she heard nothing, aside from a phone call in March to say that her case was still in their system.

“I’m incredibly uncomfortable walking down that section of St. George at night now, and it has only been amplified by my lack of faith in Campus Police,” Jane said. When asked whether she would recommend that someone in a similar position report to Campus Police, Jane’s answer is a firm “no.”

Marginalized students face additional barriers when reporting sexual assaults. “All students may face barriers to reporting, including feeling uncomfortable dealing with the police, feeling scared they will be judged or revictimized,” said Wandio, adding, “These barriers tend to be worse for racialized women, women with disabilities, trans* women, etc., partly because there are a lot of harmful myths surrounding how those groups experience — or don’t experience — sexual violence.”

A difficult process

Even when students do decide to report, the results can be disappointing. “The process is not so easy, mainly because initially it was not very clear as to how one is supposed to go about reporting a sexual assault,” said Anjali.

Mary*, a student at Victoria College, cites similar issues with reporting her assault. “I did not know how to file a report with the university or how it would be received… I was afraid of filing a report with the university or my college as [the assailant] was a star student at the university and I didn’t want my name put in the public.”

For many, a lack of knowledge about what constitutes sexual assault also prevents cases from being reported. “I wasn’t aware that it was sexual assault nor the fact that alcohol [inebriation] was not consent,” said Mary.

Even formal reports are difficult to quantify; according to Blackburn-Evans, the university does not maintain central statistics of Code cases at the investigation stage; they only keep track of cases where a hearing was held. The number of these cases will be available at the end of the year.

* Name changed at student’s request