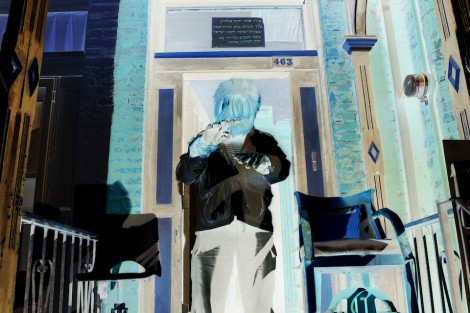

[dropcap]From[/dropcap] the street, 463 Bathurst looks like any other building on the block: a narrow-windowed residence of asphalt and brick basking in the fading colours of fall. But look closer and you’ll see a quote by Aldous Huxley etched onto the front steps: “I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin,.

Welcome to the humble abode of Reg Hartt, The Cineforum, a chaotic, two-story living space and private theatre specializing in eclectic alternative film screenings. Ever wondered what the experience of Murnau’s Nosferatu scored to Radiohead’s Kid A would be like? Come to the Cineforum and find out.

“Cecil Taylor [the noted American jazz pianist and poet] said that the key to success in the arts is to find someplace small and in your own city,” Hartt tells me. “A space where you can present your own ideas on a regular basis without being interfered with. I think I’ve found that space.” He gestures around the small kitchen we’re sitting in, shelves overflowing with crockery and books. Just down the hall, the 40 seat theatre room boasts a mammoth subwoofer, crisp projection technologies, and two insulated spectrum speakers cleverly hidden behind monster masks. Everything in The Cineforum is made with care — it’s just as much Hartt’s character as it is the theatre’s character. You can tell as soon as you sit down. It exudes genuineness, an independent and handcrafted quality tangible only to small spaces that are deeply loved.

[pullquote-default]“the resilient man is like water; he plunges into every crevasse, fills it up and moves on, without losing the core of their being. Living is a whole series of deaths and resurrections”[/pullquote-default]

Hartt regularly holds lectures and screenings in this velvet-lined incubator; intimacy and a reckless disregard for convention are essential to his process. Disagree with his opinions and selection? He couldn’t care less. Doing things on his own terms has always been the highest priority for Hartt, well past any financial validation or recognition from the public.

This attitude existed long before The Cineforum’s inception. Before establishing the theatre in the early 90s and becoming friends with esteemed journalist Jane Jacobs, the film archivist acted as a cinema studies consultant at Rochdale College — an educational experiment in student-run curriculum and cooperative living in the early 70s. He was, and always will be, a student enrolled in the school of cinematic exploration.

Despite turning 70 next June, Hartt shows no signs of slowing down; upcoming projects include a new layered score for The Birth Of A Nation, rescoring Von Stroheim’s Greed, and a second production of his own revision of The Epic of Gilgamesh (which has recently found an American publisher). As he attributes to the “I Ching,” a text whose teachings Hartt applies to everything, along with the epiphanies afforded by psychedelics, “the resilient man is like water; he plunges into every crevasse, fills it up and moves on, without losing the core of their being. Living is a whole series of deaths and resurrections,” he says. “You get used to something, it falls apart. You have to regenerate and find something new, and preferably something that finds your interest. By virtue of curiosity and the necessity of growth, you continue.”

For Hartt, this continuation embeds itself in trying out new ideas. He chalks this ideology up to the culture established by Walt Disney Productions and Warner Bros. Animation. Namely Warner’s story sessions, called “no sessions,” the only rule being that each employee was never allowed to say no to any risky idea or permutation. This attitude would go on to create Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes. These were the minds responsible for the golden age of American animation. The Tweety cartoon, that would circulate around his imagination as a child, was one of his earliest experiences with the magic of movies.

Now what does he think about today’s motion picture industry? Believe it or not, the answer still involves Disney movies. “The secret to the lifeblood of the movie industry is not government grants, it’s franchising. Franchises are stars, directors, producers, themes and connected stories. Every great work of literature is at least three parts — beginning, middle, and ending. Movies are like short stories: even a four-hour movie is not long enough to do the subject justice. They demand an episodic format to deal with great works, especially in adaptation, and I think you can do that with movies, if they are done right.”

Regarding his legacy, Hartt takes a more reserved stance, telling me he doesn’t mind if he has something to leave behind. He tells me a story about monks in Southeast Asia, and how they construct these beautiful sand mandalas, complex ritualistic symbols meant to focus the attention of spiritual practitioners. They pour over them with excruciating attention to detail, only to sweep them away after a few days. “The world is being cluttered with all these mandalas that we’re saving, and for what?” Hartt asks. “We don’t want our work to be swept away. We want something to endure after we’re gone, yet I’ll be quite content to have nothing left behind after I’ve passed.”

Hartt maintains that his true achievement is being able to teach other people to do things that matter to them. At the end of the day, that’s more important than anything else. “All of the people that have lived with me or entered through here leave transformed, with a new sense of what they can do,” Hartt exclaims. “We’re here to work miracles. We’re not here to work with anything less than that.”