On September 18, an article was published in The Varsity entitled “Why the most ballots should constitute a win.” The author speaks in favour of the current first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system.

Although early in the article it states that “the main grievance against FPTP is its apparent undemocratic nature,” the author argues for the fact that regional representation should be our primary concern when picking the leaders of our country.

Even if there are other benefits offered by the FPTP system, an electoral system being undemocratic is not a minor concern. In fact, the democratic nature of any given electoral system should be our first concern.

When evaluating the results of the last federal election, Fairvote Canada reported that 49 per cent of voters cast their ballots for a losing candidate. This means that over 8.6 million people could have stayed home during the last election, and under the current framework, the results of the election would have been exactly the same. This situation causes many to feel dissatisfied with the electoral process.

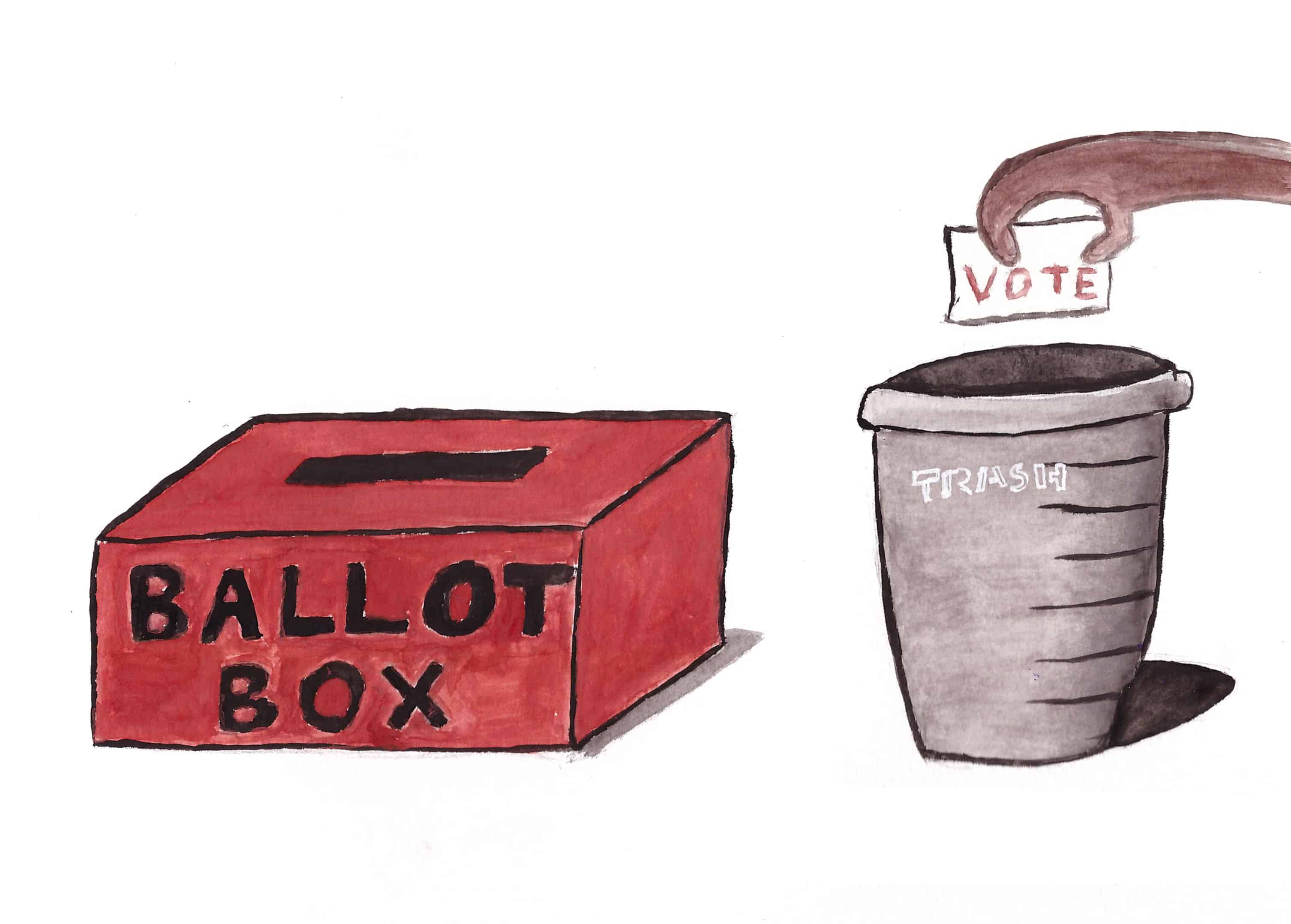

Imagine being a Liberal supporter living in a rural Alberta riding, which has been won by a Conservative candidate for as long as the party has existed. There is no real motivation for you to vote, for you know what the result is going to be and who is going to win. Moreover, even if you are aware of other Liberal supporters in your riding, so long as there is a definitive, predictable majority that supports another party, there is little motivation to vote in a FPTP system. In other words, when the most votes can guarantee a party a majority, you, as a supporter of a different party, might as well cast your ballot in the trash.

This is where a proportional representation (PR) system may come in handy. There are varying forms of PR, but in general it looks like this: the popular vote directly correlates to how seats are distributed in the House of Commons. This ensures that there is a direct connection between the support that each party garners within the community and the amount of representation that candidates obtain in the end.

Take the 2015 election: the Liberal Party received 39.5 per cent of the popular vote. Under the FPTP system, this equated to winning 184 seats or 54 per cent out of the 338 available. In a PR system, the seat count would be closer to 134, arguably more representative of the actual support the Liberals received.

Furthermore, under the PR system, it wouldn’t matter what a voter’s political inclinations were compared to those within their geographic proximity; every vote would count towards a Member of Parliament (MP) being elected. This means the voices of all get to be heard, not just those fortunate enough to agree with their neighbours.

Although previously expressed opinions in The Varsity point to the PR system’s lack of regional representation, the current political culture of FPTP does not operate with regional representation in mind either.

This is because the overwhelming majority of party campaigning is conducted at the federal level. Voters become very familiar with the policy and leadership of a party, but in the end, they often know very little about the party’s candidate in their riding.

In the past election, for example, voters in Toronto Centre voted for the Liberal Party — not necessarily Chrystia Freeland, the Liberal candidate in that riding.

The regional representation argument breaks down even further when you consider that MPs often have little choice in how they vote. Party discipline is so severe in the House of Commons that MPs can face strict consequences for not voting with their party.

Though this is a problem independent of the electoral system itself — and one that should be explored in more detail — it undermines an MPs ability to represent their voters’ voices, and therefore, one of the alleged benefits of the FPTP system falls flat.

With all this in mind, why does Canada still use a FPTP system? In short, it’s because change is hard. People have become so accustomed to the system that shifting to a new way of thinking can seem like treading unknown waters.

There are also political reasons, which are more pressing: politicians like having power, and FPTP makes it that much easier to hold onto it, given that majority governments are easier to obtain. This sounds great for those who support the government in power, but it can also create volatile, inefficient shifts in policy if the government frequently changes, for each new government may possibly completely invalidate previous work.

What is clear, however, is that neither of these reasons are particularly compelling in their case to maintain the status quo.

Christopher Chiasson is a second-year student at Innis College studying Political Science and Economics.